Members of the Geijutsuza with Shimamura Hogetsu in the middle (mustache) 1913. Public Domain.

Something Old and Something New

In 1912, just as he graduated from the Tokyo Academy of Music, Nakayama Shimpei took two jobs. The first was as a teacher of music at Chigusa Elementary School in Tokyo. The second, which he kept secret for two years because it involved moonlighting in the tawdry, low-brow world of musical entertainment, was as the music director for Shimamura Hōgetsu’s theater troupe: the Geijutsuza. This second job would lead to the creation of the formula for prewar Japanese popular songs: make modern songs that sound Japanese.

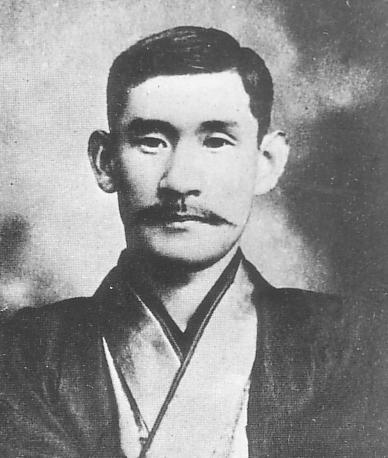

Who was this music director who influenced Nakayama, one of Japan’s top prewar composers of music? In one of his most well-known photographic portraits, Shimamura Hōgetsu (1871-1918) stares at the camera from his desk chair. Surrounded by books, the Waseda University professor of English Literature looks young but intense. His mustache is well-groomed, but not particularly symmetrical. He’s just slightly disheveled but charmingly clean-cut. His light-colored kimono and darker haori are draped perfectly. With the desk next to him, sitting in a Western-style chair, and books on the shelf behind him, he radiates scholarliness. As this photo reveals, Shimamura was a writer who combined Western culture with Japanese traditions. Shimamura’s goal was to use literature to move Japanese society forward into the modern world. He was intensely passionate about this mission.

Public Domain

Shimamura Hogetsu in his study.

Shimamura also mentored Nakayama, who wrote “Kachusha’s song”(Kachusha no uta, 1914) and was one of several popular song composers who set the pattern for Japanese popular music in the first half of the twentieth century. Nakayama’s songs put Japan Victor, Inc. into a dominant position in record sales for most of the 1920s. His frequent use of a specific team of lyricists, singers, and musicians whose work he trusted created an early version of what might be called a “hit-making machine,” able to crank out top-selling recordings at an amazing pace.

Public Domain

Shimamura Hogetsu

Nakayama gave much credit for his strategy of popularizing songs and his production skills to the things he learned from Shimamura, who was a kind of father figure for the composer. Nakayama lived in Shimamura’s home to earn his board while he attended the Tokyo Academy of Music. He was also given duties at Waseda Bungaku, a literary magazine that Shimamura edited Through Shimamura’s contacts there he met some of the brightest lights of the Taisho literary world, including some who would eventually become his lyricist collaborators: Noguchi Ujō, Kitahara Hakushu, and Sōma Gyofu.

Nakayama got to know Shimamura in and out of the house. His talents led Shimamura to ask him to compose songs for the Geijutsuza productions, and by training the actors to sing those songs, he built connections in the dramatic and musical worlds, as well. As the protege of Shimamura, Nakayama learned to write songs that sounded new to Japanese audiences, but not too new. Shimamura demanded that they had to be able to recognize the Japanese tradition in the modern songs that Nakayama wrote for Shimamura’s stage plays.

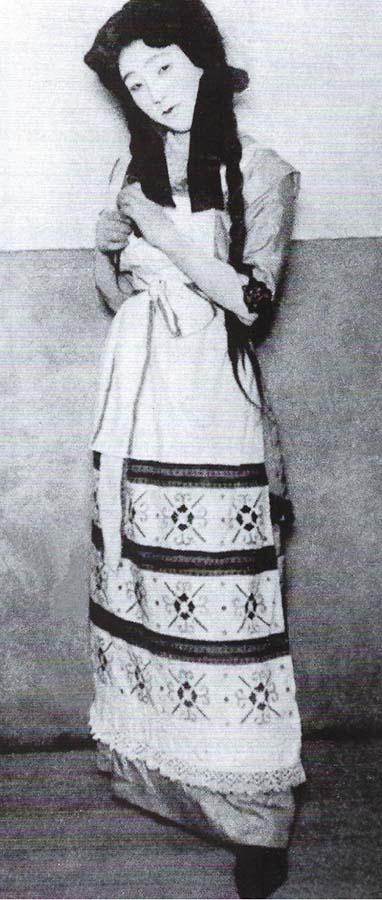

This is exactly what Nakayama did with “Katyusha’s song.” He wrote a song using a Western major scale, but then borrowed the idea of a five-note scale from the work of Japanese bureaucrat Isawa Shuji and American Luther Whiting Mason to make the song sound slightly “Japanese.” He taught, by luck as it happens, Matsui Sumako to sing that song without accompaniment - a Western scale mimicking a Japanese scale, sung along a single melody line like a Japanese song. “Katyusha” was the most advanced song of its time, yet it was also acceptable to the ears and expectations of the Japanese audience. When it was recorded and the record sold ten thousand copies in its first year, it became clear that Shimamura was onto something. His formula worked.

Public Domain

Matsui Sumako 1915

When Shimamura died in 1918 of the Spanish flu, Nakayama had some choices to make. He declined to join with Shimamura’s associates and publicly blame his mistress, Matsui Sumako, for luring him out of the family home and eventually to his death (which may have contributed to her decision to hang herself a month later). Instead, he used the contacts he made at Waseda Bungaku to find a way to move on. He reconnected with Noguchi Ujō, who had been pressuring him to record a song they had co-created in 1915. Originally titled “Karesusuki,”(Withered pampas grass), it was a sad song about poverty-stricken people looking for a way out. With no future and a hard life, love was the only thing they had in the world.

I am withered grass on the riverbank

You, too, are withered grass on the riverbank

We are, in this world, both of us withered grass that never bloomsWhether we live or die

Or are taken by the current

Why don’t we both go live

As boatmen on the Tone River

Nakayama and Noguchi argued about the title. Nakayama, fresh out of the world of popular theater, thought Noguchi’s desire to title the song Karesusuki would turn off consumers, who would not like the sad and lonely connotations. They decided to go with Nakayama’s more general title: “Sendō kōta” (The boatman’s song). Nakayama’s instincts were on target. The song caught on, sold big, and propelled his and Noguchi’s careers forward. This was the song that launched a thousand boats. Its sadness was emphasized by its use of a five-note scale like the kind developed by Isawa Shūji and Luther Whiting Mason and their gagaku musician friends, but in a minor key, and with a slow rhythm. “Sendō kōta” was such a big hit for Japan Victor, Inc. that Japan Columbia, Inc., one of two other major international record companies now competing for sales in Japan, ordered its composers to come up with something like it.

Public Domain

Matsui Sumako 1919

Nakayama had come up with his formula: make songs that sounded Japanese, about regular people, with lyrics by poets who also wrote about regular people and the struggles of living in a modern, industrial society that was changing fast. Those songs sold well. Nakayama and Noguchi became frequent collaborators from that moment until Noguchi’s death in 1945. The pair of them, following the advice of Nakayama’s mentor Shimamura Hōgetsu to give the audience new sounds, but not too new - songs that sounded a little new and a little old - songs that surprised, but were not too confusing. These songs were for regular people, but they were not just simple songs. They were songs for common people living uncommonly complicated lives in a rapidly industrializing and changing Japan.

—---------------------

Patrick Patterson, Music and Words: Porducing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952, New Studies in Modern Japan (Boston: Lexington Books, 2018, https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781498550352/Music-and-Words-Producing-Popular-Songs-in-Modern-Japan-1887%E2%80%931952.

Nakayama, Urō. "Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku " In Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku/Nenpu. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980.

Saburo Sonobe, Enka Kara Jazu E No Nihonshi (Shokosha, 1954). 358.

Showa Ryūkōkashi (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, n.d.).46.

Add new comment