The “Butterfly” effect: how a Boston music teacher and an ambitious Japanese bureaucrat changed Japanese music

In December of 1990, I viewed my first Red and White Song Contest (Kōhaku Uta Gassen) on Japanese TV. In this program, a red team and a white team each made up of musicians compete to outperform each other while entertaining the audience in the last four hours of the year, ending in a climactic group song.

I was mystified when I heard that “traditional” final song and realized that I was hearing “Hotaru no hikari” (The light of the fireflies) a Japanese version of “Auld Lang Syne.” I struggled to understand. Was this a Japanese song that Americans had adopted? Was it an American song that the Japanese had adopted? Was it something that everyone in the world sang at the dawn of the new year, and I just had not been “in the loop?” I asked my Japanese friends. They told me it was a traditional Japanese song for New Year’s eve.

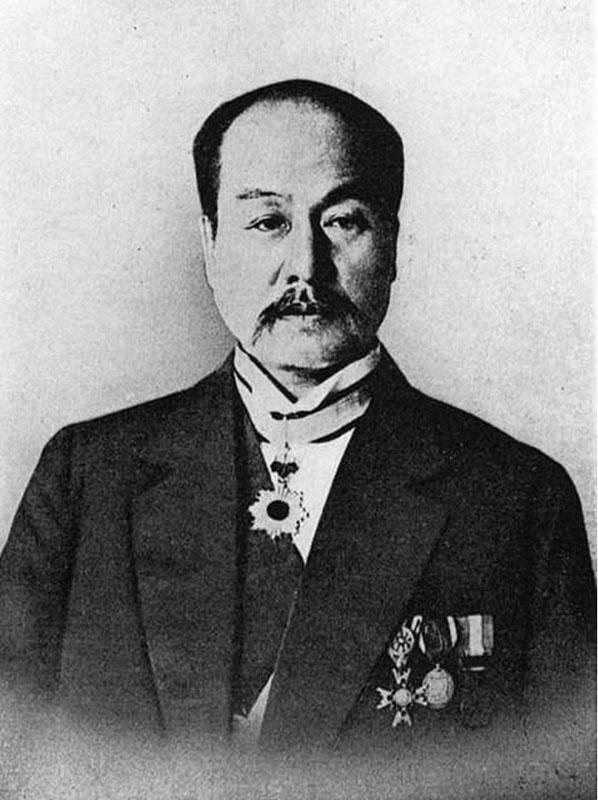

Years later, I learned that Auld Lang Syne is neither American nor Japanese nor a “world song.” It came from Scotland to Japan via the United States courtesy of the father of Japanese music education, Isawa Shūji (1851-1917). Isawa was not a mythical figure lost in the mists of time. He lived in modern times, in the transition between Japan’s Tokugawa and Meiji periods. He did not take traditional Japanese music and single-handedly mold it into something both new and yet still uniquely Japanese. He was, in fact, no musical genius out to broaden Japanese horizons nor an ideologue out to create new music for a new world. Rather, he was a bureaucrat looking for his chance to leave a mark on Japanese history, and by random chance, he hit upon music education as his vehicle. Mundane though his situation may have been, it turns out he was ambitious. His goal, he wrote himself, was to blend Western music into Japanese traditions, “taking the best out of both European and oriental music.”[1] He succeeded, with the help of a Boston music teacher, mostly in importing and imitating Western Music.

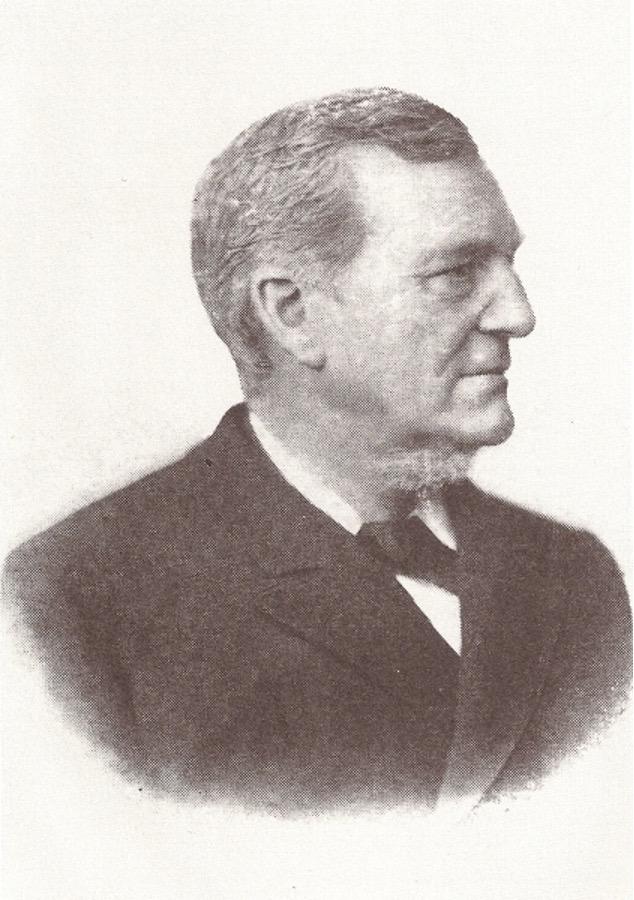

In 1875 the Japanese government sent Isawa, an ambitious Education Ministry official, to the United States to study Education in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. There he met Luther Whiting Mason (1818-1896), a music teacher for the Boston Public Schools. Isawa brought Mason to Japan to help him organize Japan’s new music education system. Thus Japanese school children learned Western notation, harmony, melodic styles, and instruments. The choice of Western music meant that Western musical systems and instruments became the official standard. Isawa’s efforts led to the creation of the Tokyo Academy of Music, now the Tokyo University of the Arts. It also led to the publication of the first official elementary school songbook, which included mostly Western songs translated to Japanese. One such song came from an old Scottish folk song called “Lightly Row” which Mason and Isawa turned into the famous children’s song “Cho cho” (Butterfly) in their songbook.

To make Western music intelligible to the Japanese before the twentieth century, Isawa and Mason decided to find ways to mimic Japanese sounds in their modern, Western music. Specifically, the innovations that Isawa and Mason started were using the Western staff notation system and tones based on Western scales as represented on a piano keyboard. They enlisted the help of Japanese traditional “gagaku” court musicians to create scales in the Western tone system but that sounded like Japanese scales. They concentrated music education on Western instruments, and Isawa encouraged schools, from his new position in the Ministry of Education, to use a pedal-driven organ or a piano to accompany children while singing songs in the classroom. Initially, Japanese instruments were not included in the songs borrowed or composed by Mason and Isawa, but eventually, their parts transcribed to Western staff notation, they were included. In the early twentieth century, the Tokyo Academy of Music began to include some classes in Japanese instrument technique to complement its mostly Western focus.

By borrowing Western musical notation the Tokyo Academy of Music led the way toward the standardization of music notation across all instruments and styles, Japanese and Western. This changed the tonality and playing styles of Japanese traditional instruments, but it also made them compatible with Western instruments and with each other. One problem that occurred, though, was a sense of the loss of tradition by either abandonment or modification to suit Western needs. Isawa had to explain the need for this without resorting to a critique of Japanese traditional musical styles. To do so, he relied on what has become a tired argument, but one that, at the time, had some explanatory power. Isawa explained the gagaku - Japanese court music - was a pure musical expression. He noted its origins in Chinese court music and ventured that even deeper in time it had shared the same roots as Western Classical Music. The two had developed along different lines but were related. For this reason, it was appropriate for gagaku musicians to assist in the creation of scales that were capable of re-merging the two, and it was also true, he claimed, that both gagaku and Western Classical music were edifying, pure forms that led to the cultural improvement of their listeners.

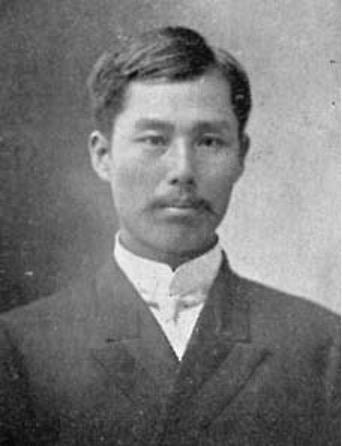

Popular music, however, according to Isawa, was low music with no real purpose save entertainment, and that led inevitably to music about inappropriate, even bawdy subjects, and celebration of the lives of undesirable people, low-class laborers, and antisocial types. This was different from the type of music that he wished to encourage with school music education. For that reason, he chose to teach Western Classical music. It wasn’t until the 1900s, after composers such as Tamura Torazō, a teacher at the Tokyo Academy of Music that Isawa founded, argued that school songs should be more closely related in words and music to the real lives of students, that music education and popular songs began changing to reflect Japanese musical traditions and experiences.[2]

Isawa Shuji changed Japanese music. His ambition channeled through the Meiji government’s desire to modernize Japan, in part by including Western music in Japanese children’s education, brought Western music to Japan as an institution. This fit well with the Meiji modernization program from the top down, and with Western ideas. To justify his choice of Western musical education, Isawa first built an institution - what became known as the Tokyo Academy of Music - and then seeded that academy with Western musical ideas and instruments. He worked with Luther Whiting Mason and Japanese court musicians to find ways to integrate Japanese instruments, particularly those of gagaku, with Western musical ideas and methods of notation. As a justification for his conversion of tunings, Isawa referenced the importance of gagaku - music for emperors - and found ways to connect that music to the Western classical tradition, as if the two were cousins. Doing this changed Japanese conceptions of music completely. It made possible the production of popular music in what might be thought of as the Meiji Way - industrialized, mass-produced, music for the unspecialized commoner who had no musical training but could play stereo with the best of them. The irony is that this mass-appeal popular music for sale on the open capitalist market was not at all what Isawa had in mind when he convinced Mason to come to Japan and change its musical culture.

Notes:

[1] Isawa Shuji, quoted in Herd, "Change and Continuity", 4.

[2] Eppstein, 60-92.

Bibliography

Eppstein, Ury. The Beginnings of Western Music in Meiji Era Japan. Lewiston, Queentston, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1994.

———. "School Songs before and after the War: From 'Children Tank Soldiers' to 'Everyone a Good Child'." Monumenta Nipponica 42, no. 4 (1987): 431-48.

Fujie, Linda. "East Asia/Japan." In Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's Peoples, edited by Jeff Todd Titon. New York: MacMillan, Inc., 1992.

Fujie, Linda "Popular Music." In The Handbook of Japanese Popular Culture, edited by Hidetoshi Kato and Richard Gid Powers. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989.

Fumio, Koizumi. "Musical Scales in Japanese Music." In Asian Musics in an Asian Perspective: Report of Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1976, edited by Koizumi Fumio, Tokumaru Yoshihiko and Yamaguchi Osamu. Tokyo: Heibonsha Limited, 1977, 1984.

Galliano, Luciana. Yōgaku: Japanese Music in the Twentieth Century [in Italian] [Yōgaku: Percorsi della musica giapponese nel Novocento]. Translated by Martin Mayes. Lanham, Maryland and London: Scarecrow Press, 2002.

Harich-Schneider, Eta. A History of Japanese Music. London: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Herd, Judith Ann. "Change and Continuity in Contemporary Japanese Music: A Search for National Identity." Dissertation, Brown University, 1987.

Hosokawa, Shuhei, and Christine Yano. "Popular Music in Modern Japan." In The Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music, edited by Alison Tokita and David W. Hughes, 345-62. Aldershot, Hampshire, England ; Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate, 2008.

Monbushō, Daijin Kanbō, and Chōsa Tōkeika. "Japan's Modern Educational System: The First Hundred Years." Tokyo: Research and Statistics Division, Minister's Secretariat, Minister of Education, Science and Culture, 1980.

Nakayama, Urō. "Nakayama Shimpei Song Catalog." In Nakayama Shimpei Song Catalog and Chronology. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980.

———. Nakayama Shimpei Song Catalog and Chronology [in Japanese] [中山晋平作曲目録・年譜]. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980. Biography.

Patterson, Patrick M. Music and Words: Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2019.

Soeda, Azenbo. Ryūkōka No Meiji Taishō Shi [ 流行歌の明治大正史]. Tokyo: Tōsui Shobō, 1933. 1982.

Sonobe, Saburo. Enka Kara Jazu E No Nihonshi [演歌からジャズへの日本史]. Tokyo: Shokosha, 1954.

Sonobe, Saburō , Yazawa Tamotsu, and Shigeshita Kazuo. Nihon No Ryūkōkashi Sono Miryoku to Ryūkō No Shikumi [ 日本の流行歌史]. Tokyo: Ōtsuki Shoten, 1980.

Yano, Christine Reiko. Tears of Longing: Nostalgia and the Nation in Japanese Popular Song. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 1995.

Add new comment