Forging the formula: the making of Japan’s first “hit song,” 1914

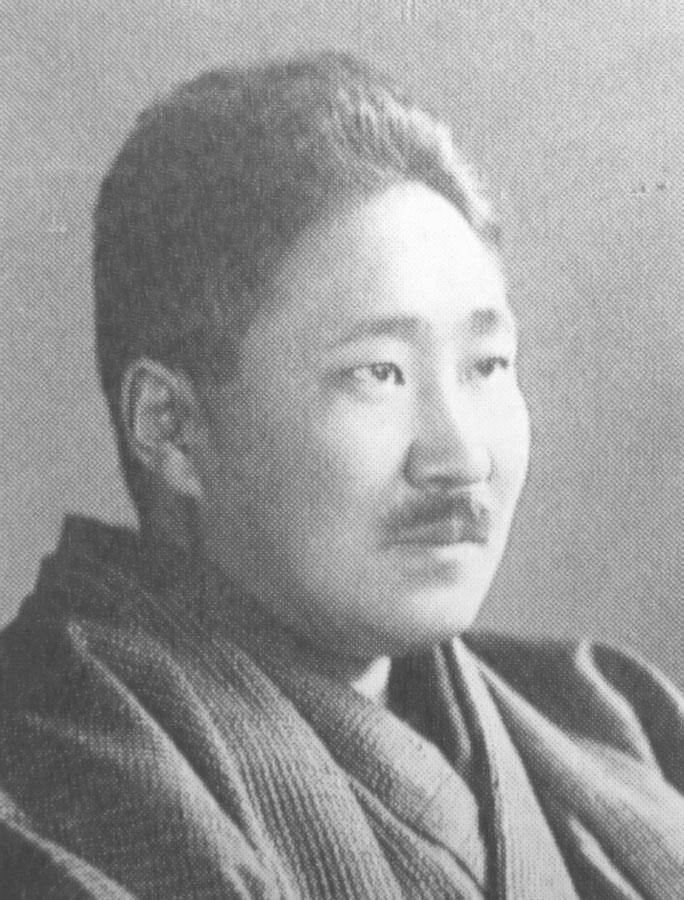

In 1912 a graduate of the Tokyo Academy of Music, Nakayama Shimpei, wrote with humility to his older brother, a government employee in Nagano that “by some mistake, I have been allowed to graduate.” Thus began one of the most illustrious popular music careers in Japanese history. Nakayama can rightly be said to have set the pattern for Japanese popular music in the twentieth century - what is now considered almost its own genre, simply called “Shimpei-bushi” (Shimpei songs).

Nakayama came from a family of farmers who had fallen on hard times. Inspired by a brass band that visited his hometown of Nakano in 1905, he learned as a boy to play music, grew up to become a school music teacher, and then found his way to Tokyo to study at Isawa Shuji’s Tokyo Academy of Music. After graduation, he found himself dissatisfied with the salary provided by the Tokyo elementary school that hired him to teach, and began the risky (because it was associated with performing, and performing was associated with prostitution and gambling) sideline of working as a composer.

To do this, he used the composition tools he had learned in the academy to defy Isawa’s preference for classical music and write popular songs for popular plays and, eventually, records. Unlike Isawa, Nakayama saw two key reasons to write popular music. First, it was music that more people would have the opportunity to hear, and he wanted to encourage a modernizing spirit among his fellow Japanese. Second, it was much more likely to make money - something the poverty-stricken Nakayama discovered when his first song, “Katyusha’s song,” was recorded and became the biggest-selling record in Japan in 1914.

Nakayama wrote “Katyusha’s song” for a musical version of Tolstoy’s The Resurrection, which had done well in England. The play’s author, Shimamura Hōgetsu, Nakayama’s mentor and a Waseda University literature professor, hoped to use musical theater to introduce the Japanese to Western literature. Shimamura chose The Resurrection because he thought it was close to Japanese sensibilities. One of the tenets of his thought was the idea that to make something new popular in Japan, you had to make it modern, but also familiar (Japanese) enough so that audiences would not get confused and walk out. So he hired Nakayama to write a Western song to be sung by the play’s main female character, Katyusha and told him to make it Western, but sound Japanese. Nakayama did so, and in the process created a new musical genre - Shimpei-bushi - songs by Nakayama Shimpei. Katyusha was the first of many songs that had the Nakayama ‘sound’ - a recognizable set of musical choices that made them easy for people to identify and label with his name. Nearly all of them sold like hotcakes in Japan in the 1920s.

First, of course, he wrote it using a Western major scale. He did not bother with the Japanese-sounding five-note scales developed by Isawa, Mason, and the gagaku musicians. He wrote it on piano and intended it to sound Western, probably to emphasize the fact that it was to be sung by a character who was Russian, not Japanese. The content of the song, which followed emotional patterns of lost love, sorrow, and duty to others - an aestheticized sadness - was what would make it sound familiar to a Japanese audience.

It was also set to be sung, of course, by a Japanese actress. Matsui Sumako, who was to play the lead role of Katyusha in the play, was already redefining the role of stage fame. She was considered beautiful whether she wore a Japanese kimono, or a western blouse and skirt. She was well-known for her torrid affair with the show’s producer, Shimamura, and this led to a fantasy among many men of her sexual availability. In short, men thought she was hot. Women, on the other hand, saw her as a feminist icon. As she started her role of Katyusha, she was just coming off of a successful run as Nora in the Japanese version of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Nora’s defiance of male expectations and determination to strike out on her own was inspiring and transferred its aura to Matsui. In sum, women looked up to her. Because men and women in the audience were drawn to her, Matsui was the perfect vehicle to popularize Shimamura’s play. Since Shimamura was clearly in love with her, she was probably also his only choice for the role in any case.

As it turns out, Matsui Sumako was not an accomplished singer: she could not sing in tune with any instrument, so Nakayama had to teach her to sing the song a capella. After trying for weeks to teach the song to her with piano accompaniment, Nakayama gave up and rearranged it to use a single melodic line, reasoning that Matsui’s vocal failings would be less obvious if she sang it alone. This also worked to the song’s advantage, however, as audiences familiar with the single melodic line of most traditional Japanese music found it easier to follow, a coincidence working in favor of Shimamura’s maxim. More, like many postwar Japanese enka tunes, it was sung by a woman, but written from the point of view of a man. Sumako sang about her character as if she were the man who was abandoning her. This was another first by which Nakayama began to set a pattern for Japanese popular music.

With all of these innovations in a single song, it is not a great surprise that when Matsui, in need of some extra cash and invited by the manager of Kyoto’s new record company, Orient Records, recorded the song and named Nakayama as its composer, the song took off, selling more than 20,000 copies in its first year - twice as many records as there were record players in Japan.

Nakayama Shimpei

In a case of life imitating art, “Katyusha’s song” prefigured the fates of Matsui and Shimamura. Shimamura’s wife forced him to leave home when she discovered a poorly-hidden love letter from Matsui on his desk. Apparently smitten, he carried on his affair with Matsui anyway during the nationwide tour of The Resurrection in 1914. Their behavior was scandalous, and Nakayama tried to convince his mentor to give up his paramour and return home to his family. Unrepentant, Shimamura and Matsui returned to Tokyo and quite literally shacked up in Shimamura’s office at the Geijutsuza his drama company’s theater. Shimamura began working on his next play in 1915 but caught a virulent strain of influenza and died. Shortly after that, Matsui Sumako committed suicide to follow her lover in death leaving Nakayama in charge of music for a theater company without a producer and with no star to inspire his songs. Perhaps it is no surprise that the sadness of the words to Nakayama’s second hit song, “The Boatman’s Song” is unrelenting. Written in 1915 with lyricist Noguchi Ujō, and released on record in 1921, the song, alternately titled “Dry grass on the riverbank” (Karesusuki) is a bluesy paean to the harshness of life and love. While it is not “Blues” in a technical sense, Nakayama Shimpei set the pattern for Japan’s popular music style with songs about themes that would have played well in an American Blues song – poverty, hard labor, hopelessness, and doomed love. Anyone familiar with enka today would recognize these well. Shimpei-bushi, the pattern for Japanese popular songs even today, became popular as songs about the difficulties of real life and real love - quite a distance from the edifying classical music of beauty that Isawa Shuji had imagined he was bringing to Japan.

Bibliography

Nakayama, Urō. "Nakayama Shimpei Song Catalog." In Nakayama Shimpei Song Catalog and Chronology. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980.

———. Nakayama Shimpei Song Catalog and Chronology [in Japanese] [中山晋平作曲目録・年譜]. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980. Biography.

Patterson, Patrick M. Music and Words: Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2019.

Soeda, Azenbo. Ryūkōka No Meiji Taishō Shi [ 流行歌の明治大正史]. Tokyo: Tōsui Shobō, 1933. 1982.

Sonobe, Saburo. Enka Kara Jazu E No Nihonshi [演歌からジャズへの日本史]. Tokyo: Shokosha, 1954.

Sonobe, Saburō , Yazawa Tamotsu, and Shigeshita Kazuo. Nihon No Ryūkōkashi Sono Miryoku to Ryūkō No Shikumi [ 日本の流行歌史]. Tokyo: Ōtsuki Shoten, 1980.

Add new comment