Reverse-engineering popular songs

In his book The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory (2015), John Seabrook claims that Swedish DJ turned popular song producer Denniz PoP and his proteges learned to reverse engineer famous popular songs. They identified and recreated the successful elements successfully so well that they became dependable hit-makers in the 1990s. Denniz PoP, and his protégé Max Martin analyzed hit songs and used the key elements to create an endless chain of hits.

It’s true. The most successful songwriter of all time is Max Martin. He’s produced hit songs for the Backstreet Boys, Roxette, Brittany Spears, Taylor Swift, and many more. However, Denniz Pop and Max Martin did not invent the idea of reverse engineering successful songs. Reverse engineering is simply the process of examining the components of a successful product in great detail to be able to reproduce that product. This is not a modern idea, and nor is it a Western idea. Japanese songmakers were reverse-engineering songs in the early 20th century.

We already know that music is a business. To be successful at selling songs, any popular artist needs to keep making “hits”. So it is hardly a surprise that music composers in the 1920s used the elements of songs that were already successful to build their own new songs. These things happened from the very beginnings of recorded popular music.

Japan’s first popular song was 1914’s “Katyusha’s song” (Katyusha no uta), which I discussed in an earlier post. The song was written by a music teacher and part-time musical theater composer named Nakayama Shimpei (1887-1952). The “Geijutsuza” theater which commissioned Nakayama’s song was in the business of introducing a new product to its audience: Western drama and literature. “Katyusha’s song” was intended to be part of a musical version of Tolstoy’s short novel The Resurrection, which the producer of the Geijutsuza, Shimamura Hōgetsu (1871-1918), had seen in London. He wanted a version to show in Japan, but he did not want the version produced in London. So he reverse-engineered it, using the ideas that worked for him and adding others to appeal to a Japanese audience with different sensibilities from English theatergoers and no experience with Western plays. To sweeten the deal Shimamura told Nakayama to write the song in such a way that it was Western to fit the play but sounded Japanese enough to be familiar to the audience. Nakayama was thus consciously blending genres and national styles fit the tastes of his audience and fit the song into a play reverse-engineered from an English musical version of a Russian novel. The result was a smashing success. When the record sold twenty thousand copies in its first year, Nakayama made out like a bandit. The record company, Orient Records, which was on the verge of bankruptcy when they recorded the song, became a solvent company. The singer, Matsui Sumako, became the most famous actress in Japan, and Nakayama earned enough money to live comfortably for the first time in his life. Reverse-engineering the play, and the song - Nakayama had used Western musical techniques and notation, avoiding Japanese instruments and manipulating the Western scales to sound slightly Japanese in the way that popular school songs were already being written in Japan since at least the beginning of the twentieth century.

“Katyusha’s song”

Nakayama learned from his unexpected success and continued to add Western elements to his songs. Since we are thinking of reverse-engineering in this post, it is important to recognize that Nakayama himself was not entirely reverse-engineering. Isawa Shūji reverse-engineered the Western musical system with the help of Luther Whiting Mason and Japanese Gagaku musicians. Nakayama simply built on their work, using it to make popular songs. Thus he was in many ways the inventor. What he created, many others wanted to emulate, at least in part because so many of his original ideas led to songs that made money. So Nakayama’s techniques became the source material for reverse-engineering. He was trained in Western music, so he was writing Western songs that sounded Japanese. As he wrote for more adaptations of Western plays, including Carmen, he added more Western-style and Japanese elements. “Katyusha’s song”, for example, had included a brief aside in which the singer enunciated the sounds “la la” during a verse. Nakayama considered himself quite innovative for thinking of it to solve a problem with matching Shimamura’s words to his melody. In Carmen’s “Gondolier’s song,” he added the same element intentionally. He also included a feeling of melancholy sadness that evoked Japanese ideas of miren (longing). He continued mixing genres, eventually using a Western scale that was adapted to sound Japanese by removing the fourth and seventh tones, and by adding a shamisen rather than a guitar to many of his songs after 1923. Thus hybrid music was one of the first ways in Japan’s nascent popular music market to reach a new audience and sell songs. Nakayama’s songs were engineered to suit the tastes of his audience. Other songwriters would use these techniques in their own work.

The clearest case of reverse-engineering a “Shimpei bushi” - a genre so named because all Nakayama’s songs were so popular the constituted a genre in themselves, and his first name was Shimpei - came in 1928 after two of Nakayama’s most popular songs became the source material for reverse-engineering. Nippon Victor released Nakayama’s “Sendō kouta” in 1922 and “Habu no minato” in 1928 with great success. Nippon Polydor executives hoped to find a way to repeat that market success with their own song, to be released also in 1928, named “Kimi koishi” (Longing for you), from lyricist Otowa Shigure (1899-1980) and composer by Sasa Kōka. Their orders were to make a song like “Sendō kouta” but more upbeat.

Kimi Koishi

Sasa used a minor yonanuki scale for “Kimi koishi,” just as Nakayama had for “Sendō kouta.” It sounds a bit sad, but “Sendō kouta,” makes it sound positively joyful. Sasa echoed the successful parts of “Sendō kouta,” but he and Otowa made it a love song. They also sped up the tempo. They de-personalized the song, so that it depicted love from a distance, which made it more appealing to a wider audience. “Kimi koishi'' was designed to be a popular song by reverse engineering “Sendō kouta.” It had all the elements that had made “Sendō kouta'' so popular, and none of the bits that made it depressing.

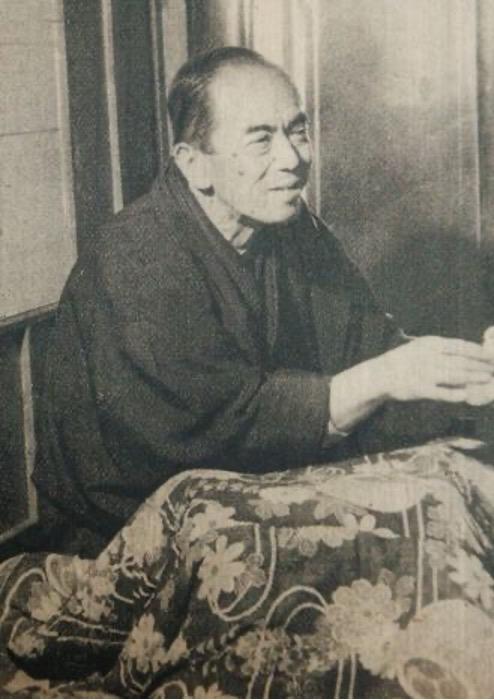

Sasa Koka 朝日新聞社, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

So we know that reverse-engineering to maximize sales is a good popular song strategy that songwriters frequently use today. What is interesting is that the case of “Kimi koishi” shows that it wasn’t an idea pioneered in the 1980s. It was already being done by the 1930s. “Kimi koishi” was a big hit with music consumers, selling even more records than its Shimpei bushi models. It is still sung today, and recorded by singers looking to add to their credibility by singing prewar popular songs. Most consumers were never aware that it had been based on earlier tunes - instead, it became one of the many songs in the growing catalog of popular music, known at the time as ryūkōka. It was just different enough from the Nakayama songs that it sounded original, and added to the vast diversity of songs as the popular music genre grew in prewar Japan.

Sources

Frith, Simon. Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Koga, Masao. Uta Wa Waga Tomo Waga Kokoro. Tokyo: Nippon Tosho Center, 1999.

Kokka Sasa and Shigure Ōtowa, "Kimi koishi" (Tokyo: Nippon Columbia, 1928).

Nakayama, Urō. Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku/Nenpu [in Japanese] [中山晋平作曲目録・年譜]. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980. Biography.

Seabrook, John. The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory [in English]. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2015.

Add new comment