Eri Chiemi had a distinguished career in Japanese music covering a wide variety of genres. (Public domain photos)

Underrated: The Showa Era's best female vocalist wasn't Hibari Misora

By Scott Kikkawa with an introduction by Jayson Chun.

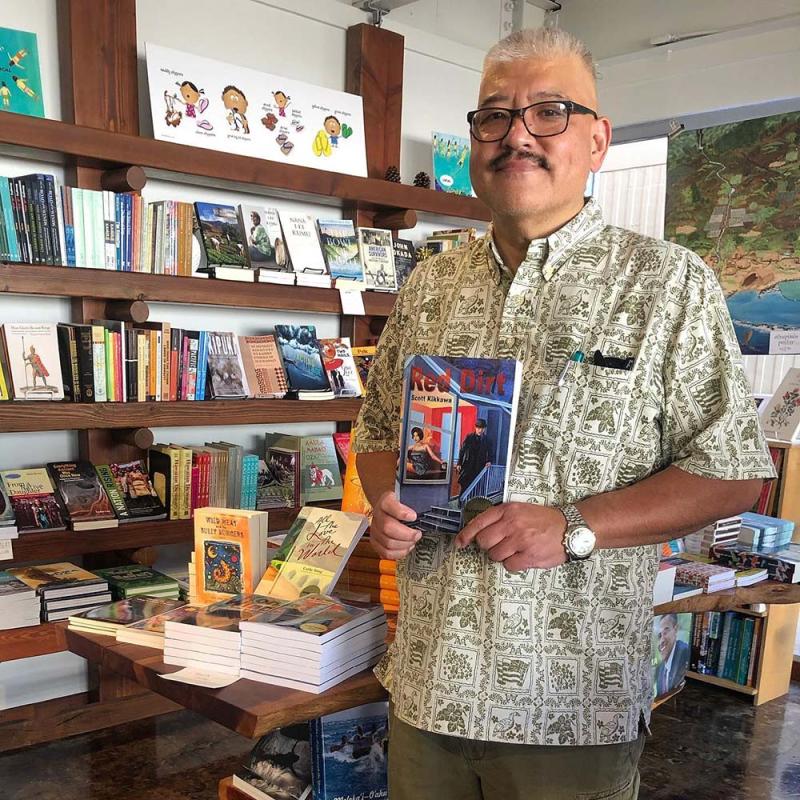

Scott Kikkawa has given many talks about Hawaii literature and noir, for example in the Reading room series.

Introduction

Today’s guest post is from acclaimed Hawai‘i writer Scott Kikkawa. A US Federal Law Enforcement officer by day, he also has a “night job” as a novelist. He made his writing debut with his award-winning novel Kona Winds (2019) published by Bamboo Ridge Press, and writes noir novels set in postwar, pre-statehood Honolulu featuring his protagonist Japanese American police detective Francis “Sheik” Yoshikawa. He has written two more noir novels set in territorial pre-statehood Hawai‘i: Red Dirt (2021) and Char Siu (2023). He has a fourth publication set for early 2026, Sporting Girl. Kikkawa also has written short stories in the Chris McKinney-edited Honolulu Noir (2024), in The Hawai’i Review of Books (THROB) and in Kyoto Journal.

His short post today ties in with the theme of transnational culture by reflecting the profound impact that Japanese singers had in postwar territorial Hawai‘i. As Christine Yano points out, the postwar years were a time where Hawai‘i Japanese, who made up a plurality of the island’s population, could reconnect with their Japanese roots. During the war, it was dangerous to explore one’s cultural identity, because the Japanese community was under heavy suspicion for disloyalty to the United States, with community leaders forcibly arrested and interned. Thus local Japanese played down their Japaneseness by using only English, avoiding Japanese foods, clothing and language. But with the end of the war and having proven their loyalty to the US, they could reestablish ties with Japanese culture. Thus, Japanese singers like Misora Hibari and Eri Chiemi came to the islands to perform to enthusiastic Japanese American audiences. Kikkawa is a fan of 1950s American style and culture, and is fascinated by how singers like Eri Chiemi learned to sing American-style jazz (usually by performing on US bases).

In an interview, Kikkawa notes how he has taken on the role of a researcher in making sure that his novels are historically accurate:

I love research and the many forms it takes. I peruse photographs at the State Archives, Bishop Museum and online. I am fortunate enough to have been given access to the Center for Labor Education and Research (CLEAR) at UH-West Oʻahu by Dr. Bill Puette. I talk to professors in the UH system who are friends of mine, and listen to my mother’s anecdotes of being a young person during the period. And I read, read, read. I have amassed a personal reference library on territorial Hawaiʻi with volumes on subjects ranging from World War II martial law to labor strikes to police memoirs. I spent a month or so researching before starting my manuscript and continued to research throughout the process of composition and revision. It never really stops.

I hope you enjoy his writing (and hope there will be more upcoming pieces from him) and how it reflects the Pop Pacific, with its eclectic mix of Japanese, American and Hawaiian culture.

- Jayson Chun, University of Hawaiʻi - West Oʻahu.

---------------------------------

Underrated: The Showa Era's best female vocalist wasn't Hibari Misora

.

Eri Chiemi in Los Angeles, circa 1953. Public Domain photo.

I have an aunt who is an avid fan of Hibari Misora. Aunty Gracie is the youngest of my grandparents’ eight children, and the rest of them are gone now, including my father who was closest in age to her at eight years her senior.

Aunty Gracie is now the matriarch, and as such, her word is incontestable. She’s such a Hibari fan that her daughter, my cousin Corinne, named her own daughter Misora.

Don’t get me wrong, I think Hibari is a great entertainer. Her world-famous rendition of “Kawa No Nagare No You Ni” is an anthem which is Japan’s equivalent of Barbara Streisand’s belting out “On A Clear Day”. The song has been covered by international artists. It might be fair to say that Hibari is Japan’s best-known female vocalist.

Best-known, but, for my money, not the best.

I’m not trying to pick a fight with Aunty Gracie. I’m just saying that when it comes to great female vocal performances of mid-century Japan, nobody comes close to Eri Chiemi.

To be fair, within Japan, Eri may have had just as much notoriety as Hibari in her lifetime. She, Hibari and Yukimura Izumi starred in the “Sannin Musume” movies together (think Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra and Jules Munchin in “On the Town”, and you’ll get the general idea of what these pictures were like) and all had their share of deserved attention.

Clip the 1955 film “Janken Musume” featuring (l to r) Yukimura Izumi, Eri Chiemi and Hibari Misora. Hibari is in yellow on the left, Yukimura is in blue in the middle, and Eri is dressed in red on the right.

But when it comes to who is best known overseas, inevitably Hibari is the only name among the three that registers any recognition. This is especially true among Hawai‘i Japanese Americans, though both Hibari and Eri had toured the islands in the postwar period. Those who know Eri’s work are almost like a secret society.

I myself discovered her as I was searching for kayoukyoku music while writing the first draft of my first novel, Kona Winds. I found a collection which included the likes of Hibari, Frank Nagai, and The Peanuts (these were the two miniature kimonoed girls in the birdcage in Godzilla vs. Mothra).

I think I was half-asleep listening to the collection until I heard Eri’s “Kushimoto Bushi” with its Latin beat and driving brass backing her big voice. It was a revelation.

True, both Hibari and Eri have colorful backgrounds (Hibari had a domineering stage mother and organized crime handlers) but Eri’s is ever-so-much cooler: she was married to Takakura Ken (Gangster-movie tough guy leading man, a Japanese DeNiro) and died choking on her vomit in her sleep at age 45 in 1982. Like a rock star.

Above all, though, was Eri’s voice. She had a traditional enka voice and she had a jazz voice. Versatile. Damn good at both. I once heard a scratchy recording of her singing “Love is Here to Stay” backed by the Count Basie Orchestra. Count Basie. Holy shit. I thought it was Ella Fitzgerald at first.

I think that saying Hibari Misora was a better singer than Eri Chiemi is like saying Doris Day was a better singer than Nancy Wilson. Maybe apples and oranges to a certain extent, but, come on.

I’m fortunate to have a friend, Professor Michael Furmanovsy of Ryukoku University in Kyoto, who shared his research with me as I prepare my next crime fiction manuscript. Few in the English-speaking world know more about mid-century Japanese popular music than Michael, and he, too, appreciates the work of Eri Chiemi.

Eri Chiemi made her big breakthrough in Japan with her 1952 cover of Tennessee Waltz, sung in both English and Japanese.

.

Chiemi Eri performing at a concert in Tokyo, 1954. She, like many other local jazz musicians, performed for US troops on bases during the Allied Occupation (1945 – 1952) Public Domain from Sankei Graphic, Oct 24, 1954.

So, it’s with apologies to Aunty Gracie that I say there’s really only one Showa-era kayoukyoku singer I listen to when scrawling my first drafts, and it ain’t Hibari Misora!

- Scott Kikkawa

------------------------------

.

Scott Kikkawa is a fourth generation Japanese American raised in Hawai'i. Currently a federal law enforcement officer, the New York University alumnus is the author of three noir detective novels set in postwar Honolulu—Kona Winds (2019), Red Dirt (2021), and Char Siu (2023) and numerous other short stories. He can be contacted at scottkikkawa@gmail.com.

Discussion Questions

- Who does the author say is the best female singer of her time (not Hibari Misora)?

- Why did Eri Chiemi sing American jazz and perform on U.S. military bases?

- Why do you think Hibari Misora became more famous globally than Eri Chiemi?

- What does the author’s discovery of Eri's music (while writing his novel) tell us about rediscovering "hidden" cultural figures?

- In your own culture, is there a talented person who was overshadowed by a more famous figure? How might they be rediscovered today?

- Why do you think recognizing figures like Eri Chiemi—even if less known—matters for understanding cultural history and identity?

Add new comment