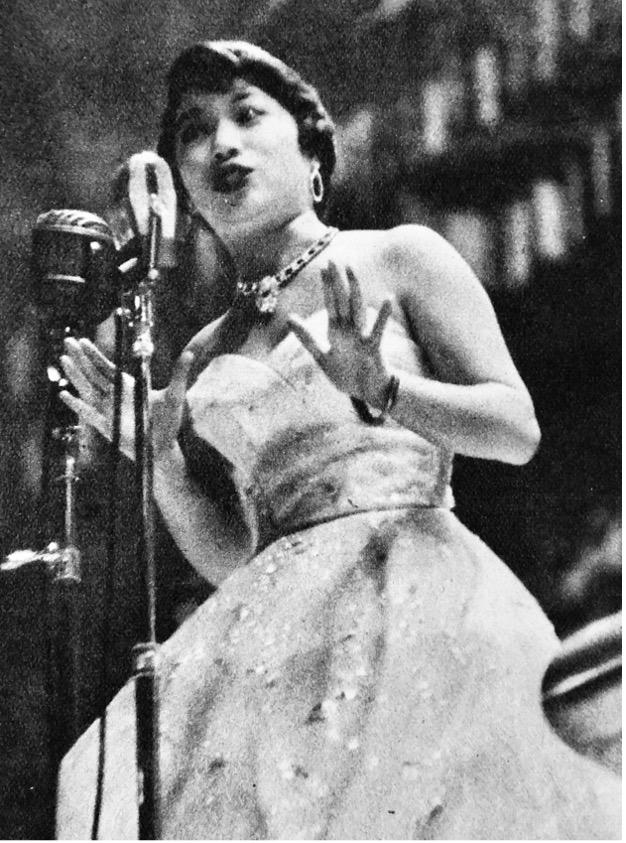

Chiemi Eri performing at a concert in Tokyo October 3, 1954. Singers like Chiemi and local jazz musicians performed for US troops on bases during the Allied Occupation (1945 – 1952) Public Domain from Sankei Graphic, Oct 24, 1954.

American Bases: Crucibles of the Pop Pacific

The scene was Japan in 1947. The bus drove to the musicians gathered with their music instruments by the train station entrance, in a Tokyo still recovering from bombing and war.

"Is there anyone who is open as a musician?" the driver inside would ask.

"You trumpet, come."

As the driver detailed what musicians they needed, the musicians gathered into the bus and formed a band on the spot to play at U.S. base clubs. This scene was repeated daily, with 20-30 buses lined up for musicians to play for various bases like Yokosuka Navy Air Corps Oppama Base or Atsugi. These musicians were among the few Japanese allowed to enter the American bases, and these gigs paid well.[1]

For musicians in Japan and Korea in the years following the war in 1945, the ability to play the latest American jazz and pop hits was important. When masses of unemployed, refugees and demobilized soldiers struggled to find work, a gig at a US military base provided a decent income. Given the competition for these jobs, musicians needed to be able to play the latest in American hits and sing unaccented English, or else lose their job to another musician.

Public Domain

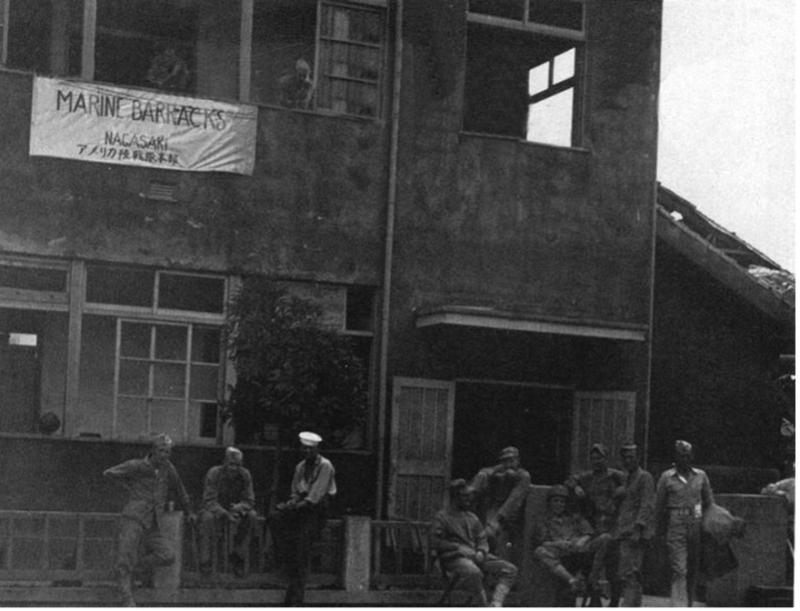

View of the U.S. Marine Corps barracks in Nagasaki, Japan, in September 1945.

American bases – contact zones of the postwar Pop Pacific

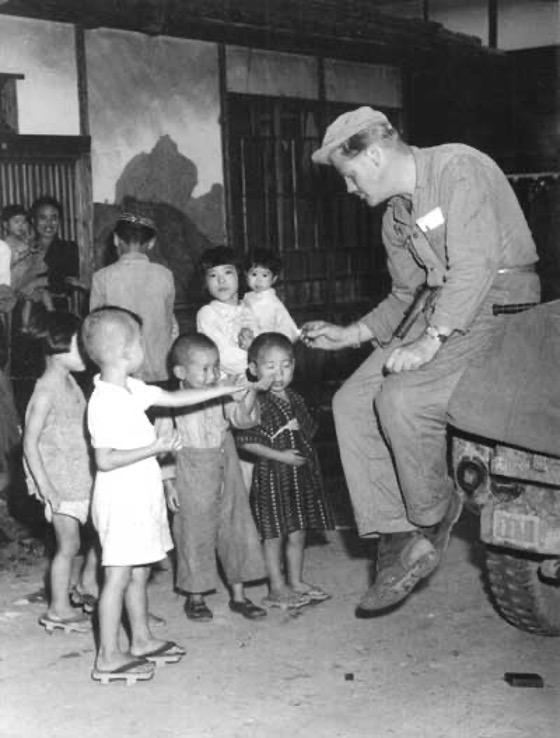

The competition between these musicians to learn and play the latest in American songs reflects the dominance of US bases in postwar and 1950s Japan and Korea. With reconstruction from war and physical survival commanding priority, most ordinary civilians lacked disposable income to buy records or see live music. Thus, musicians survived by finding employment on US bases. Military authorities wanted entertainment for the troops, and hundreds of clubs sought musicians who could play the music that American troops wanted to hear. Many singers sang for the American troops, in dedicated clubs usually off limits to natives, except for base workers and singers. During a time when most people struggled to survive, base towns provided employment for musicians and served as the crucible for the postwar music scene.

Another photo of Chiemi Eri performing at a concert in Tokyo October 3, 1954.

Musicians in both nations competed for these lucrative gigs, similar to the cutthroat competition that young people today undergo to become K-pop or J-pop idol singers. In Japan alone, there were 500 clubs, divided into different levels for officers, non-commissioned officers, enlisted men, and civilians. Clubs were also segregated by race with white and African American soldiers socializing at different clubs. Bands and musicians were ranked by a committee from A to D, with higher ranked bands being sent to the higher paying officer clubs.[2]

A similar system existed in Korea, which had over 150 camps and bases. Korean music troupes hoping to play at bases had to pass an audition supervised by entertainment industry experts dispatched by the Pentagon and were given a grade of AA, A, B, or C, and assigned to a corresponding level of shows. The top level “floor bands,” toured military bases around the country. “House bands” in the middle, played at a particular club. “Open bands” at the bottom tier, played at private clubs in surrounding base towns. Because Korean musicians had to repeat the audition every several months, this intense competition meant that Korean musicians needed to learn as many US musical styles and keep up with the latest US music hits to keep their jobs.[3]

National Archives Photo 127-N-139887

Japanese children, seeing a Marine for the first time, eagerly reach or chocolates offered them by SSgt Henry A. Weaver, III.

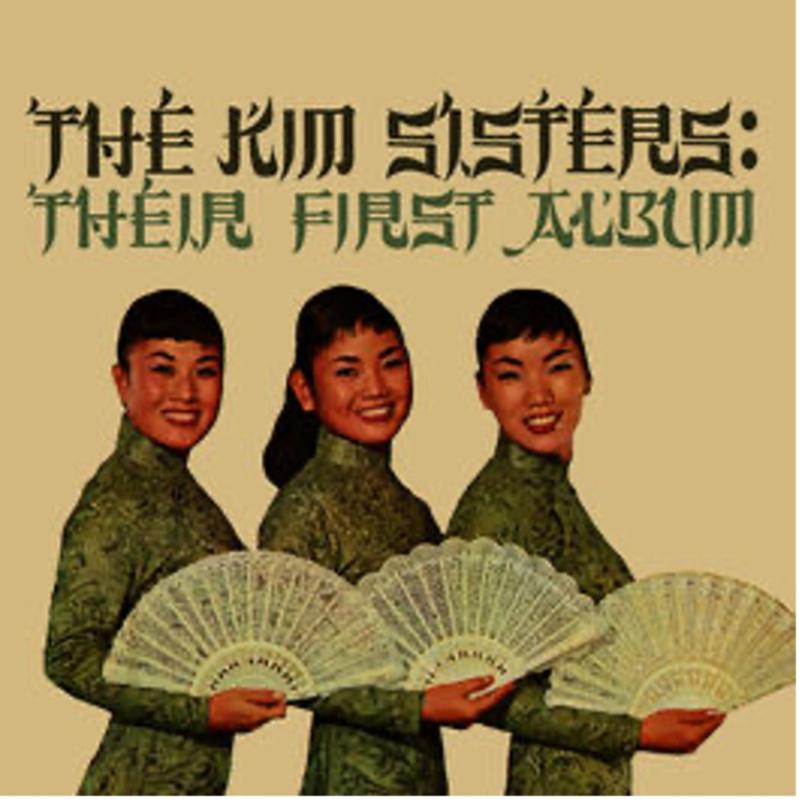

The musicians who played at the bars consisted of musicians who played in prewar jazz cafes or cruise ships, demobilized ex-military band members, and a younger group of musicians willing to learn the newest US hits. In Korea, without sheet music available, the only way to do this was to record the armed forces radio network broadcast on tape, transcribe each instrumental part, and then practice day and night in the management company warehouse.[4] If one listens to Japanese and Korean singers of the 1950s and early 60s, one is struck by their near native English pronunciation, intonation and phrasing, as seen in a young Yukimura Izumi. Because of the intense competition for gigs at US bases, being able to sing a song in perfect English meant the difference between employment and unemployment. Thus singers would repeatedly listen to US recordings until they could perfectly emulate the singers. It also helped to be female and attractive to appeal to US troops who were mostly young men. As Michael Furmonovsky points out, the military base camp was “an incubator for the careers of legendary female vocalists and movie stars Eri Chiemi (1937–82) and Yukimura Izumi (b. 1937).”[5] The same could be said for Korean singers. Patti Kim (Kim Hye-ja), one of Korea’s top divas, debuted in 1959 performing for American soldiers and by 1960, she was invited to appear on Japan's NHK TV, the first Korean performer to appear on a Japanese television show. The Kim Sisters debuted as young teenage singers at US bases in the 1950s singing for American soldiers. They spent the years 1953 – 1959 performing US songs at bases and eventually became popular entertainers on U.S. television. In fact, the Wonder Girls video “Nobody” (2009) was a tribute to them.

Public domain

Yukimura Izumi in the 1950s.

The US presence in Japan declined after the Korean War, and in Korea in the mid-Sixties. Yet, their legacy is profound. Although the base music scene died down, musicians could play at civilian clubs due to the growing Japanese economy. Many musicians turned to playing Japanized versions of US cover songs such as "Tennessee Waltz" by Chiemi Eri.

The Kim Sisters, popular in the US in the 1960s, also made their debut performing at US Bases.

Many of the base musicians became big bands backing musicians on TV song programs in the 1960s. Also, many of the staff involved in the base music scene learned to do music business in their jobs. As we shall see in future posts, businesspeople like Watanabe Misa parlayed their experiences managing talent for US bases into entertainment management companies. Who would have thought that the motley group of musicians hanging out on street corners would lead to the rebirth of East Asia’s music industries?

[1] Symposium: Yokohama, the city of jazz (2) ~Talking about the era of “Mokambo Session”~, October 10, 2004, https://www.yurindo.co.jp/static/yurin/back/yurin_443/yurin2.html.

[2] Michael Furmanovsky, “From Occupation Base Clubs to the Pop Charts: Eri Chiemi, Yukimura Izumi, and the Birth of Japan’s Postwar Popular Music Industry,” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal no. 59, 2021.

[3] Pil Ho Kim and Hyunjoon Shin, “The Birth of “Rok”: Cultural Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Glocalization of Rock Music in South Korea, 1964–1975,” positions 18:1 Spring 2010.

[4] Furmanovsky, 2021.

[5] Furmanovsky, 2021.

Discussion questions

- How did musicians get jobs at American bases after WWII?

- Why were these base gigs important for musicians in Japan and Korea in the late 1940s and 1950s?

- Why does the author describe U.S. bases in Japan and Korea as “crucibles of the Pop Pacific”?

- Can you think of a place or institution in your country that helped launch a new cultural movement—like these bases did?

- Why might working in base clubs help someone later become a music manager?

- What does this story tell us about how cultural exchange and survival strategies can spark new industries and styles—especially in tough times?

Add new comment