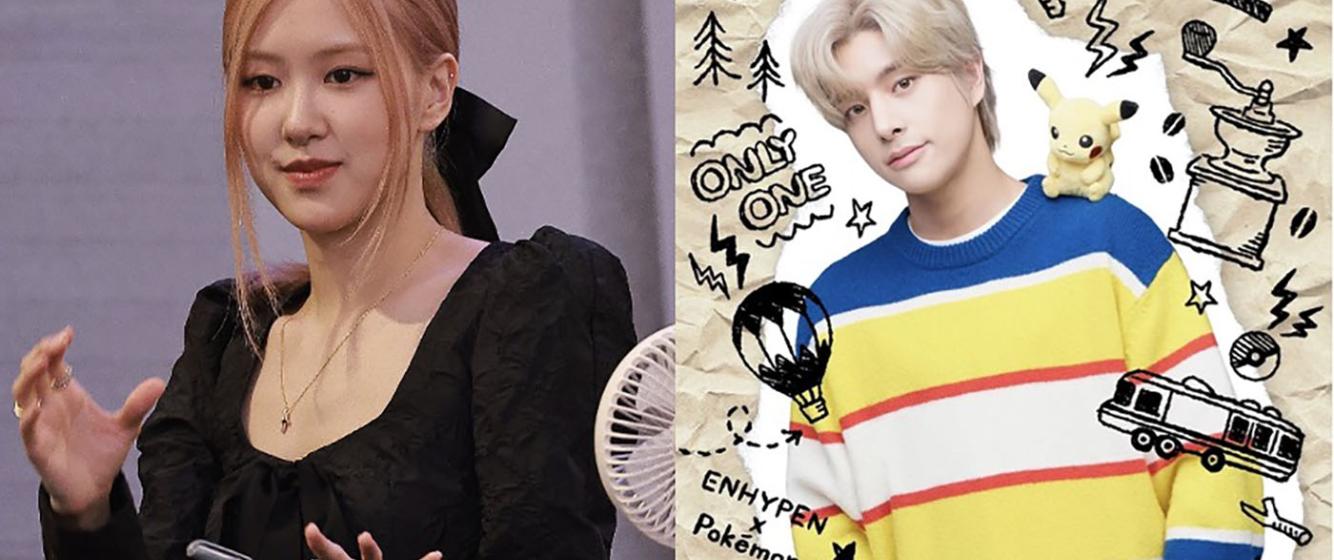

Rosé (L) of BLACKPINK, is probably the most famous Ozzie in K-pop. She was born in New Zealand to and raised in Melbourne Australia. Jae (R ) of ENHYPHEN is also from Australia.

BLACKPINK, New Jeans, Stray Kids, Enhyphen, and NMIXX: Australian K-pop Idols

I was watching New Jeans videos of, “Hype Boy” (MINJI ver.) (2022) the other day. It seems to be set somewhere in the West, outside of Korea, with suburban house parties, skating rinks, swimming pools, and a dark-skinned love interest. I couldn’t find any reference to where the video was filmed, but then I thought “why not Australia?” After all, two of the five members of New Jeans are Australians. Hanni (Pham Hanni) is a Vietnamese Australian from Melbourne. Danielle (Danielle March/Mo Ji-hye), the child of an Australian father and Korean mother, spent most of her childhood living between the two countries.

Korean-Australian K-pop stars? These idols show how globalized the world has become, and how Australia has developed a large Asian population due to changes in immigration laws in the 1990s. But while some Asian Australians fit into Australia, others faced discrimination and had struggles fitting in, and thus turned to K-pop to find their identity and employment prospects.

Ask people to name Australian singers and depending on their age, they will say BeeGees, Olivia Newton John, AC/DC, Men at Work, Keith Urban, INXS, Sia, or Kylie Minogue.

And if you ask K-pop fans like me, we will recite the “Aussie Line” of Rosé, Bang Chan, Felix, Jake, Lily, Hanni and Danielle. Most people will have no idea who they are. So, here’s a primer.

Probably the most famous K-pop Aussie is Rosé ( Roseanne Park /Park Chae-yeong) from BLACKPINK, the world’s most streamed group. The idol group STRAY KIDS, wildly popular worldwide, has two Australian members. Felix (Felix Lee/Lee Yongbok) and Bang Chan (Bang Christopher Chan), who both grew up in Sydney. Jake Sim (Sim Jae-yoon), of ENHYPHEN, grew up in Brisbane. Lily (Lily Jin Morrow) the lead vocalist of NMIXX, was born and raised in Victoria, to a Korean mother and Australian father. And as mentioned earlier, New Jeans boasts a sizable Australian contingent.

I am not Australian, so I dug deeper and found out that these K-pop idols reflect how Australia has become “a new Asian country.” In 2021, about 17.4% (or 1 in 6) of Australians are Asians, making up 4.6 million out of a population of 25.7 million (about the population of Texas). This is double the percentage of Asian population in the United States (7.2%).

The rapid growth of the Korean-Australian population came after immigration reforms in 1995. The “White Australia” policy of 1901, intended to keep the nation white and difficult for Asians to migrate to Australia, ended in 1975. By the 1990s, Australia’s economy was increasingly intertwined with Asia (especially China). By 2007, East Asian countries accounted for almost fifty percent of Australia's total trade in goods and services, more than its trade with North America or Europe.[1]

Immigration underwent huge changes in 1998, with a campaign to increase the number of international students to grow the nation’s foreign earnings. Professor Peter McDonald, in a paper on Asia Pacific migration to Australia, noticed that foreign income from international students became the nation’s third largest export in value after iron ore and coal. For many Asian students, the easier prospect of permanent residence in Australia compared to other countries became a motivation to study there.

In New Jeans’ “Hype Boy” video, Minji texts in Korean, while her black love interest texts in English. The use of Korean would not be out of place in Australia. Large-scale Korean migration happened in the 2000s. and as of 2021, there are 105,560 Koreans in Australia. Many came to Australia to escape the cutthroat competition and rat race in Korea and almost half of the Korea-born in Australia arrived in the last ten years. As a result, the young Australian K-pop stars were children who moved with their parents or were born there in the early 2000s.

K-pop idol group New Jeans. Hanni (center) and Danielle (right, in red) are from Australia.

However, observers notice that many Australians are not ready to accept the idea of the nation’s Asian future and perceive themselves as a Western nation. Differing Australian governments fluctuated in their support for multiculturalism, reflecting the public’s ambivalence.[2] In an opinion piece, Professors Pan and Gao of the University of Melbourne noted, Asian immigrants are still underrepresented in key leadership roles in society and politics, accounting for only 3.1 per cent of senior leaders in business, politics, government, and higher education. Anti-Asian feeling was exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, which many people associated with China, and Asians. More than eight in 10 Asian Australians reported discrimination during coronavirus pandemic. The professors concluded it was unlikely that anti-Asian racism would disappear unless ‘Asianness’ is embraced as part of ‘Australianness’. “Hype Boy” makes reference to this racism, as in Hyein's version of the video, she has a crush on white asthmatic boy, but in the end, he is hanging out with his friends and they are seemingly mocking her dancing.

Stray Kids in January 2023. Felix (far left) and Bang Chan (second from right) are from Australia.

For many Asian Australians, who grew up in a society where they were growing in number but still marginalized, K-pop with its hip westernized images, and relatable Korean idols, represented a way to accept their ethnicity and break stereotypes of being an outsider. Charlene Behal, who wrote of how being Asian-Australian wasn’t something that she acknowledged, remembers her sister introducing her to Felix from Stray Kids.

‘Look at this cute guy, he’s Australian.’

Hold on. What?

This captivated my interest. I’d never seen an Asian-Australian guy in a boyband before, let alone two. One music video led to another and it wasn’t too long until I ‘fell in love’ with Felix from Stray Kids, and fell into the wonderful rabbit hole that is the Hallyu Wave.

I thought it was so cool that I could relate to an idol on that level of being both Asian and Australian. I was 17 years old, and I discovered a whole new view of what it can mean to be Australian. It was the representation I never knew I needed.

Behal writes of how Australians in K-pop allowed her to embrace her identity and feel part of a community. Indeed, it is no wonder that half of K-pop fans in Australia have Asian heritage and many have taken to performing K-pop dance covers in public.

The experiences of K-pop idols show the reverse migration of Australian Koreans who went to Korea seeking opportunities. The Australian music market is still relatively small, and so an Asian Australian would have a good chance breaking out in the K-pop market. As pointed out in reddit threads and YouTube videos, K-pop is aimed at the world market, and having an English speaker in an idol group helps. I wrote in a previous post how K-pop replicated Asian American panethnicity, where people from parts of Asia can become K-pop stars. In Australia, there has emerged a critical mass of young Asian youth who speak English and have the Western aura that characterizes K-pop.

Yet, these young teens are still Australians who are asked to move to a distant country. Thus, a young Roseanne Park, who would become Rosé of BLACKPINK, thought her father was joking when he suggested she audition for a Korean entertainment company. As she told the Sydney Morning Herald in 2017,

"In Australia, I didn't think that there was much of a chance for me to become a singer – especially to become a K-pop star ... I was living so far from the country that it never really occurred to me as a possibility."

On the other hand, Jake Sim, watching BTS’ performance at the American Music Awards in 2017, decided that he wanted to become a K-pop idol. While on a family vacation in Korea, he auditioned and won a spot on a Korean audition program, eventually becoming a member of ENHYPHEN.

Reflecting the diversity of experiences, many Korean Australians found moving to Korea a foreign experience. Felix of Stray Kids could barely speak Korean while his teammate Bang Chan was born in Korea and was more familiar with the culture.

Of course, these stars can make cultural blunders, like when Danielle of New Jeans sparked an uproar among Korean fans by referring to “lunar new year” as “Chinese New Year”. This online message, which some Koreans saw as pro-Chinese and anti-Korean, led to criticism from internet users and her subsequent apology. Thus, Korean Australians, like many other diaspora members, can face criticism for being “too western” or culturally insensitive.

K-pop shows how the world is interconnected. K-pop groups like BLACKPINK can tour Australia, and be guaranteed to find an audience of cashed-up fans, for example selling out the 15,000-seat Rod Laver Arena in 2019. By being popular among the diaspora worldwide, K-pop has brought together Asian American and Asian Australian fans through social media.

So, when watching Australian K-pop idols, realize that their stories are like Felix, Bang Chan or Jake’s, and resulted from changes in immigration laws in the 1990s. As Professor Simon Marginson predicted in 2012 during the heyday of Australian multiculturalism,

“In the long-term, Australia will become an Anglo-European-Asian hybrid. We will mix British heritage governance, law and business with elements of Asian culture and demography: a kind of Hong Kong in reverse.”[3]

For those of us who live outside the land down under, the rise of Australian K-pop idols tells us it is time to look at Australia as an Asian nation.

[1] Ien Ang, “Australia, China, and Asian Regionalism: Navigating Distant Proximity,” Amerasia Journal , January 2010.

[2] Ruth Phillips, “On On ‘Being Australian’: Korean Migrants in ‘Post-Multicultural’ Australia,” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1 2021

[3] Simon Marginson, “Australia must overcome superiority complex to learn from rising Asia,” The Conversation. May 10, 2012. https://theconversation.com/australia-must-overcome-superiority-complex-to-learn-from-rising-asia-5620

Discussion Questions

- Who are some of the most famous Australian K-pop idols mentioned in the article? Do you know of any others?

- What immigration changes in the 1990s helped increase Australia’s Asian population, eventually influencing the rise of Asian-Australian K-pop stars?

- Why might Asian Australians see K-pop as a way to embrace their identity in a society where they sometimes face racism or feel excluded?

- K-pop groups often include English-speaking members to reach international audiences. Can you think of other entertainment industries (music, film, sports, etc.) that use similar strategies to appeal to global fans?

- What does the rise of Australian K-pop idols suggest about how we should view Australia—not only as a Western nation, but also as part of Asia

Add new comment