In 2014, Bora Kim, a Korean graduate student in the US wondered in her thesis what would happen if she created a K-pop band of non-Koreans. She auditioned six members and labeled the group EXP Edition, short for “experiment”. This group, made up of white performers, would become, in the words of the BBC, “The world’s most controversial 'Korean' band.”

After Kim’s MFA program ended, four of the members decided to try their luck in Korea, undergoing hours of training. Their Korean debut came in the summer of 2017, when they released a music video and performed live on a Korean variety show. What followed was a flood of hate from fans. Some accused the band of cultural appropriation - disrespectfully exploiting Korean culture.

The outrage over EXP showed a selective view of who can and cannot do K-pop. K-pop groups featuring non-Korean Asians like TWICE or EXO did not receive criticism. Lisa (Lalisa Manobal) of BLACKPINK, who is of Thai nationality, sang her solo album in Korean. The group XG, made up of all Japanese members, appeared on Korean TV music shows in 2022, speaking in fluent Korean, and singing in English. None of them were called out like EXP Edition.

Perhaps, part of the controversy reveals an unwritten code: non-Koreans in K-pop are acceptable if they are Korean American, part Korean, or recently, Asian. Thus, the “K” in “K-pop” has transformed into a term that describes “Asian” pop.

Why not use the term “Asian”? It is a “pan-ethnic” term that lumps together groups with distinct cultural identities. Importantly, it is a Western concept that is generally not used in Asia. Unfortunately, this idea of a common heritage was used by the Japanese during colonial rule in Korea to justify forced assimilation policies such as the prohibition against Korean-language media during the war years. The idea of “Asia '' justified Japan’s “Greater East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere '' in which Japan would lead a coalition of Asian nations against white European rule. So one can see why people in Asian countries would avoid this term.

The “K” in K-pop instead strongly resembles the American concept of “Asian American,” a political term invented by Japanese American Yuji Ichioka and Chinese American Emma Gee in the Third World Liberation Strikes of 1968 at San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley. This term defined an alliance of mainly Chinese American and Japanese American students who fought alongside other groups like the Black Student Union for more diversity and ethnic studies in college. Since Asians grew up in the US facing similar issues of racism and the Vietnam war, and were also lumped together by the rest of society, it made sense to work together .

This term for a political alliance became a category to describe various ethnic groups, who often had nothing in common. Although this term was vague (does it include Filipinos, Indians, and people from the Middle East?), it became popularized with the explosion of Asian immigration after immigration law changes in 1965. In the 1980s a new generation of Asian Americans found a common identity with each other, especially on college campuses. Gradually, the “American” was dropped and now the term is often just “Asian”.

Even today, “Asian” holds little meaning for people from Asia. After all, many did not experience life as a minority, and so the issues facing Asian Americans like lack of representation failed to resonate with them. For example, the movie “Crazy Rich Asians” was successful in the US, and Asian Americans saw the film as a symbol of ethnic representation. However, in Japan, it was just titled “Crazy Rich'' while in Korea, the movie failed to resonate with audiences.

The “K” in K-pop however, has more flexibility and can include different Asian groups (although Korea is at the center of this identity). This is a startling development because the panethnicity of K-pop contrasts with historical movements in Korea to keep the culture free from foreign influences. Korean culture came under assault under Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945). In post-liberation Korea, American influences from bases flooded Korean cities. Therefore the government and elites strove to protect Korea’s cultural identity. One example in popular music was Lee Mi-ja’s “Camelia Lady” (Dongbaek Aggasi, 1964), which was banned for sounding too Japanese. However, this song seemed indistinguishable from other songs popular in Korea.[1] Despite outcry by nationalists about Japanese-sounding music, Korean culture had absorbed many Japanese influences, and banning a song or two would not change this.

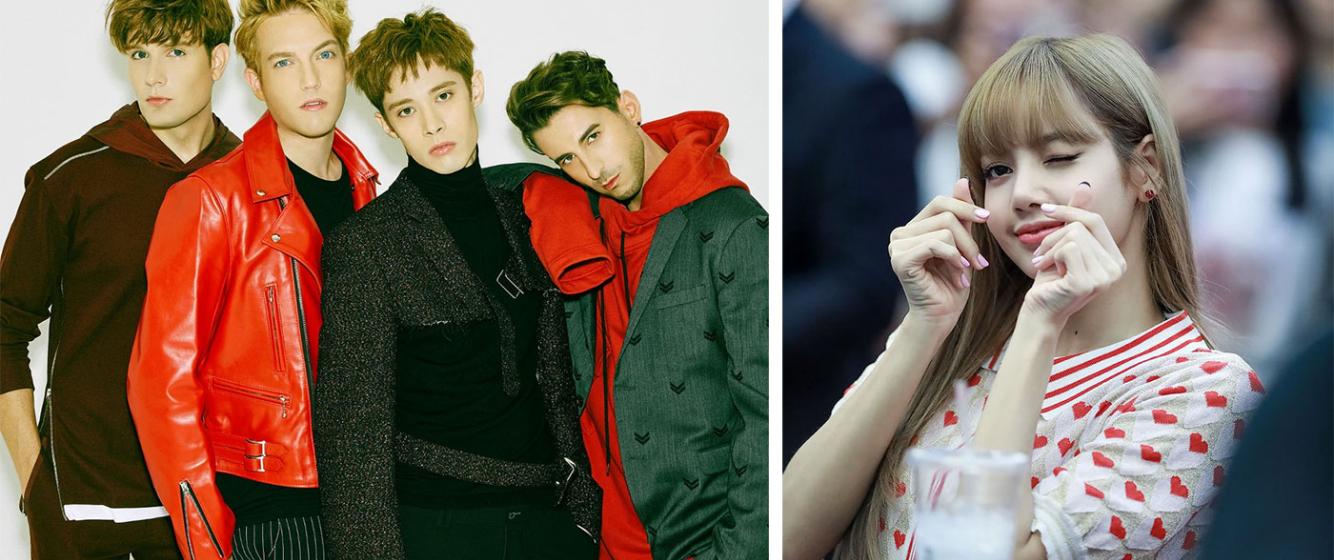

Three of the members of the influential K-pop group g.o.d (L )were Korean American or grew up in America. Teddy Park (of 1TYM), who grew up in California, produces hits for groups like BLACKPINK (R)

The “K” in K-pop widened to include the U.S. definition of “Asian”, and now represents an Asian pop culture with heavy American influences. One of the big reasons for this shift is that Korean Americans popularized K-pop in the 1990s. Korean Americans gave K-pop an “authentic American” feel to audiences. They played a vital role in bringing the “Asian American” concept to K-pop. Korean Americans or Koreans who grew up in the US were members of late 1990s groups such as H.O.T, S.E.S, G.O.D, SOLID, UPTOWN or 1TYM. Korean Americans such as Tiger JK (Seo Jung-kwon) or Tablo (Daniel Armand Lee, a Canadian who graduated from Stanford University), popularized the Korean hip hop scene in the late 1990s, and Korean American producer Teddy Park(of 1TYM), produced songs for groups such as 2NE1 and BLACKPINK.

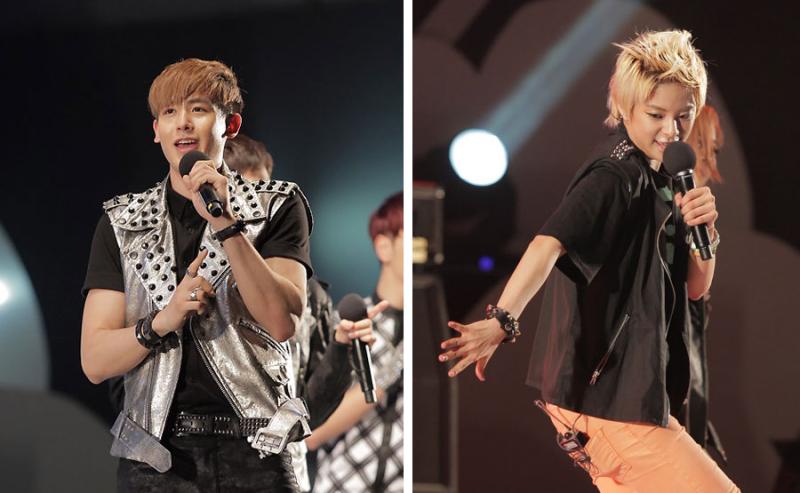

Photos by 와사비콘텐츠 -, CC BY 2.0 kr and 와사비콘텐츠 - f(x) 에프엑스 서울광장 데니의 뮤직쇼 메가콘서트 피노키오 hot summer by 와사비콘텐츠, CC BY 2.0 kr.

Thai American Nichkhun of 2PM (in 2011) and Taiwanese American Amber Liu (in 2011) opened the door for non-Koreans to perform in K-pop (so long as they were Asian).

Once Korean audiences became used to Korean American performers, it became easier in the early 2010s to accept other Asian Americans like Thai American Nichkhun Buck Horvejkul of 2PM and Taiwanese American Amber Liu of f(x). By the mid-2010s, it became acceptable to have performers from Asian nations perform K-pop so long as they sang in Korean or English.

Because of the key role of Korean Americans, K-pop has gradually widened to accept Asian performers and “K” can also refer to “Asia”. Admittedly, this is problematic because it privileges Korea, but K-pop now encompasses Asian panethnicity..

[1] Seung-Ah Lee. "Decolonizing Korean Popular Music: The “Japanese Color” Dispute over Trot" Popular Music and Society, Vol. 40, no. 1, 2017. P. 104.

Comments

A beautiful article that…

A beautiful article that speaks to the times of our contemporary moment.

Beginning with his exploration of EXP Edition, Dr. J powerfully connects K-pop to the Asian American movement of the 1960s. He asks us to reflect on our gatekeeping of K-pop. The article then guides us into understanding how gatekeeping from fans threatens to reproduce the racial constructs of Western hegemony.

Finally, the article asks us to consider expanding our understanding of "K-pop." Why do we fall in love with the music, the carefully choreographed dance routines, and the lovely members themselves? Perhaps it speaks to the ways in which we are diverse, but also very much interconnected.

Thank you, Dr. J!

Add new comment