Labubu: How a Dutch-Chinese designed elf became the unlikely face of transnational pop culture

Frenzied shoppers brawling in toy stores. Lines around city blocks. Fans livestreaming unboxing mystery packages. K-pop superstars dangling tiny creatures from designer handbags. This is the Labubu craze. A furry collectible figure with pointed ears, crooked teeth, and a mischievous grin. It looks like just another toy but has become the hot item that fans battle to obtain. Welcome to the Labubu phenomenon, 2025's most unexpected cultural earthquake.

Its popularity created so much chaos that UK retailers suspended sales after fights broke out. Pop Mart outlets in Korea shut down in-store sales when crowds became unmanageable. That’s why I’m not (yet) part of the Labubu craze since I hate crowds and fights (except for watching mixed martial arts).

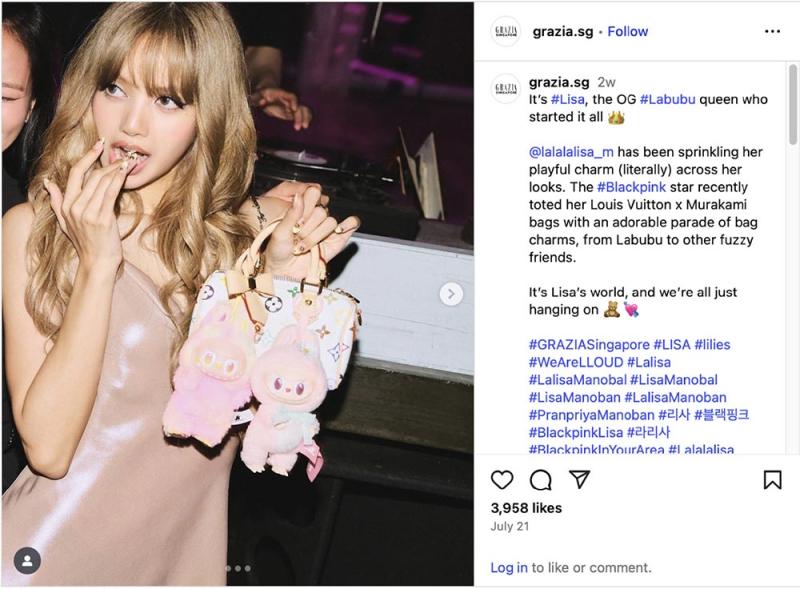

But when you can get A-list celebrities like BLACKPINK's Lisa, Dua Lipa, Rihanna, and Kim Kardashian to pose in photos themselves with the toy, you know you have a global phenomenon and status symbol. The Labubu craze shows how culture crosses borders in the 2020s.

Analysts like Ming Gao view Labubu as proof of China’s growing soft power. But for me it also reflects the Pop Pacific. This is a space where culture flows across borders and mixes in ways that resist national labels. The story of Labubu is not about one country’s success. It is about how culture now circulates in webs of influence that connect China, Korea, SE Asia, Europe, and beyond.

Nordic Roots, Global Dreams

Labubu's story began in the culturally hybrid landscapes of Hong Kong and the Netherlands. Kasing Lung, the creator of Labubu, was born in Hong Kong and moved to the Netherlands as a child. As a result, he grew up between cultures. He drew inspiration from Nordic folklore elves when creating characters for his 2015 picture-book series The Monsters. He combined elves with the ugly-cute style popular in East Asia (which manga fans like me know as busu-kawa in Japan). The result was a figure with oversized ears and teeth showing through a mischievous grin that was strange yet oddly appealing.

The characters might have stayed small if not for Pop Mart. The Chinese toy company bought rights in 2019 and adapted Lung’s art into blind-box collectibles. Each figure came in a sealed box so buyers only learned which one they had after opening it. The thrill of the unknown and the rarity of special editions drove people to buy more. The system recalled earlier crazes like baseball cards, Pokémon, or even the tulip mania of 17th century Holland. Scarcity created desire. Counterfeits soon flooded the market too to satisfy the cravings of those who wanted the limited number of Labubu. Pop Mart’s model worked. A picture-book elf became an object of international demand.

Enter K-pop: The Lisa Effect

I first heard about Labubu from my students at the University of Hawai‘I - West O‘ahu when they were debating how to get them. When I asked why they cared, the answer was simple. Lisa from the K-pop group BLACKPINK had been seen with the toys. That was enough. One celebrity sighting transformed interest into obsession.

Of course, Labubu’s popularity was more than just Lisa. The BBC reported that Labubu first became big in China around 2022 as the country emerged from the pandemic. Demand spread into Southeast Asia, showing the power of China’s regional reach. But the transformation from niche collectible to regional to global phenomenon occurred when Lisa posted photos of her Labubu collection. Her followers, known as Blinks, eagerly engage with anything their idol shows interest in, and Labubu became the latest obsession. And with over 100 million followers on Instagram, her influence was immediate. She sparked a collecting frenzy and shelves in Asia, Europe, and North America soon emptied. Fans hunted for vending machines and online shops. The toy had crossed from regional to global.

Lisa’s effect shows how cultural products spread today. She is Thai, performing in a South Korean created group, promoting a Chinese-made toy created by a Hong Kong artist in The Netherlands. The toy became a transnational object that could not be pinned to one nation. TikTok and Instagram amplified the wave. Clips of Lisa with her Labubu sparked waves of unboxing videos, parodies, and fan-made content. The craze multiplied with every repost.

Social media turned Labubu into a worldwide event. This craze was a bottom-up phenomenon built by the fans themselves. Fans built communities by sharing finds and trading rare editions. Unboxing videos became rituals. People filmed themselves opening blind boxes to capture the suspense. These easy to make videos (just film yourself opening a Labubu blind box and make exaggerated reactions) offered cheap entertainment and proof of value. They also invited viewers into a wider circle of collectors and fueled sales. Labubu became less about the toy itself and more about social presence. No wonder my students in Hawai‘i were excitedly talking about Labubu! And no wonder this craze passed me by since I hardly use social media.

The Pop Pacific Paradigm

Labubu fits what I call the Pop Pacific model. The Pacific, since the time of the ancient Polynesians, has long been a highway linking people. Today culture spreads in webs, not single directions. Labubu’s story touches Hong Kong, the Netherlands, China, Korea, Thailand, and global fandoms. In the past the United States and Europe were the dominant source of pop culture. Now Asia-Pacific products spread worldwide on their own terms. The toy’s identity is layered. Some call it Chinese while some see it as K-pop related. Others just see something fun. National labels matter less to young consumers than whether the product feels fresh and shareable.

A Reddit user described how they first thought Labubu looked creepy. As a Reddit user wrote in My Labubu Love Story:

“The very first time I saw a Labubu, I’ll be honest… I thought: “What the heck is this weird little creature?” 😅 I didn’t get it. It looked odd, kinda creepy, and definitely not “cute” in the usual way. But then… I saw another one. And another. …And suddenly I was like: “Wait… they’re kinda adorable?” “Hold on… I think I love them?””

That moment of shifting perception is at the heart of the craze. It is about repetition, familiarity, and community confirmation. Culture spreads not because people analyze it but because they slowly come to feel it.

And my wallet is thankful that I still don’t feel it (yet).

China’s Soft Power Surprise (or is it?)

China’s state media celebrated Labubu as proof of national creativity. The BBC reported that the Chinese state news agency said that Labubu ""shows the appeal of Chinese creativity, quality and culture in a language the world can understand", while giving everyone the chance to see "cool China". But Ming Gao calls it accidental soft power and points out that unlike Cool Japan or Korea’s cultural export strategies, Labubu’s success was not planned by the government as a form of overseas soft power promotion. As seen with my students, it simply caught on.

The success contrasts with struggles of other Chinese cultural exports. Chinese films can be huge domestically but struggle overseas because they're too specifically Chinese, requiring knowledge of Chinese history, culture or patriotism that international audiences lack. You get the feeling that these movies had to be approved by government officials in Beijing somewhere along the way. For example, The Battle of Lake Changjin (2021) portrays the Chinese as clever heroes outsmarting and outfighting overconfident and technologically superior Americans in the Korean War. These movies, while domestically successful, failed to gain traction internationally (obviously in the lucrative American market) due to their overtly nationalist themes and heavy-handed messaging.

By comparison, Labubu felt light, playful, and open. That difference explains its broader success.

But there are limits to Labubu’s appeal. Labubu did not gain traction in Japan. Matt Alt points out that Japan is already saturated with cute mascots so Labubu is no different than other domestic cute mascots. And Alt points out that negative news about China affects how Japanese audiences see Chinese products. I also argue that even local news like Chinese tourists behaving badly, can help create negative feelings towards China (although the vast majority of Chinese I met in China were friendly, polite and considerate). With toys like Hello Kitty and Chiikawa (which is wildly popular among Chinese) already in shops, Japanese consumers see no need to chase Labubu, a toy associated with China.

Yet in other places the toy succeeded by sidestepping heavy messaging. It showed Chinese creativity without slogans or an obvious political agenda. Perhaps this is how Jackson Wang, a Hong Kong-born former K-pop idol, who now proudly calls himself "China Man," remains popular among K-pop fans overseas. To these audiences, he plays up his international appeal rather than his Chinese national identity through collaborations with other Asian or Western artists.

The Question of Identity

One key issue is whether Labubu’s appeal comes from being Chinese. For most fans the answer is probably no. Collectability, celebrity association, and cuteness drive demand. Some fans on Reddit acknowledge Pop Mart is Chinese. Others confuse it with Thailand probably because of Lisa. This resembles how Japanese anime like Astro Boy was once stripped of local references for export. Later its Japanese-ness became a selling point as Japanese elements made it popular.

Chinese products may be on the same path. The video game Genshin Impact, for example, looks Japanese and has a Japanese name but is produced by Chinese company MiHoYo. Many players assume it is Japanese upon first sight. National origin is thus blurred as Labubu’s origins are mixed. A Hong Kong artist in Europe designed it. A Chinese company produced it. A Thai idol promoted it. Global fans embraced it. It represents hybrid identity rather than a single nation.

Looking Forward to the Future of Transnational Culture

Labubu signals larger trends for popular culture. Culturally hybrid products will dominate and will not fit neatly into one country’s culture. Social media will keep accelerating their reach. Commercial success will merge with cultural value. For China, Labubu suggests that creativity and playful design may generate more influence than state-led projects. Accidental soft power may be stronger than official campaigns or nationalist messaging. After all, I don’t see Americans clamoring to see movies where the Chinese hero outsmarts and defeats the Americans. Over time products that seem hybrid may reshape how people think of Chinese culture. Instead of pure national branding, China could become linked to creative blends.

The Pop Pacific will continue shaping culture. What matters is appeal, emotion, and community. Young people carry pieces of these cultures in bags and pockets. The forces that once came through Hollywood or state campaigns now arrive through Instagram posts and TikTok videos. Labubu is proof that influence spreads in unexpected ways.

As for me? I have not bought a Labubu yet. The long lines are enough to keep me away. Instead I spend time at gashapon machines looking for Dandadan anime figurines. Perhaps that makes me just another participant in the same psychological reward system as blind boxes, chasing the thrill of the unknown in tiny plastic capsules. Labubu itself may not draw me in, but the cultural shifts it represents are impossible to ignore.

Discussion Questions

- Ming Gao calls Labubu a form of accidental soft power for China. What does that mean? How is it different from traditional government-planned cultural influence?

- How is Labubu a product of the Pop Pacific? What does this term mean, and how does Labubu reflect that idea? Can you think of other pop culture examples that blur national or cultural lines?

- Why did Lisa from BLACKPINK have such a huge impact on Labubu’s global success? How do celebrities shape what becomes popular across countries?

- Labubu was created by a Netherlands-based Hong Kong artist, sold by a Chinese company, and promoted by global stars. Is it still useful to say a cultural product belongs to one country?

- What role did TikTok and Instagram play in making Labubu a global craze? Why do people enjoy unboxing or collecting videos, and what does this say about how we build community today?

- Labubu succeeded where many state-approved Chinese films failed. Why do playful hybrid products work better internationally than nationalist movies like The Battle at Lake Changjin?

- Have you ever bought or followed something because a celebrity posted about it? How does your own experience with trends compare to the Labubu story?

Comments

Discussion Questions

Add new comment