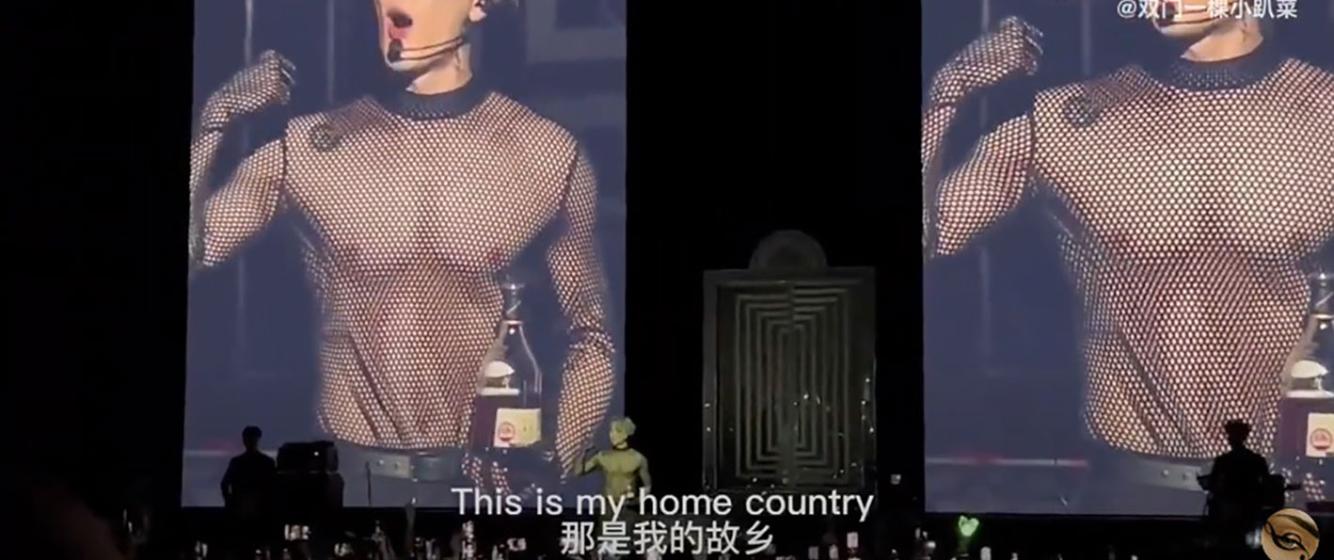

On January 12, 2023, in London while on his world tour, Hong Kong-born performer Jackson Wang, who left the K-pop group GOT7 in 2021, gave a speech on stage passionately defending China from Western media criticism.

Wang proclaimed to cheers from the audience:

This is my home. This is my home country.

Listen, listen, there’s so much f***** media talking about b*******, it’s not like China.

Media, f******* media. Propaganda b*******.

If you travel to China one time, you’ll feel like, damn, this is a dope place.

His speech met with approval from Chinese online fans. However, he was also undermining some of the key components of the Chinese government’s policies. In 2021 the government announced a ban on effeminate boy bands. Yet, Wang wore garish makeup and a black see-through mesh shirt. In earlier concerts, he drank on stage, gave lap dances to fans, swore in English, and preached a message of being true to one’s self, “As long as you keep it to yourself, you know what you are doing, you are self-protected, and you know your standard, that is what Team Wang is all about.” This was a far cry from the message of cultural conformity the Chinese government promoted. As a performer, Wang encapsulated the ambiguity of being a national performer in a transnational genre. His antics reflected China’s “Generation N” who grew up under free market reforms: nationalistic, but also influenced by world popular culture trends.

Chinese performers reflect the ambiguous relationship between pop culture and the Chinese government. Performers must be careful of running afoul of government censors and nationalistic online opinion in China, while the Chinese government struggles to control the growing cult of celebrity fan culture. After the Communist takeover in 1949, the People’s Republic of China mostly cut off western cultural influences. With the market reforms of Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, China became a hybrid market socialist economy under political control by the Communist Party. Over the next several decades, the Chinese economy exploded in growth, living standards dramatically improved, and Chinese youth took up Western music, movies, and fashions. The recent generation of Chinese youth, known as “Generation N” is highly nationalistic, representing a generation of Chinese youth educated under a nationalistic curriculum and proud of China’s transformation into a wealthy superpower. But what they are proud of is vague and diverse: the Chinese government, Chinese culture, or individual Chinese like entrepreneurs and scientists transforming China?

By Wild And Sexy - https://wildandsexy.tistory.com/entry/d, CC BY 4.0; By wjs852 - 190601 음악중심 미니팬미팅 잭슨 (1), CC BY 4.0.

Jackson Wang as member of GOT7 (2014) (L), Wang at a mini fan meeting outside "Show! Music Core" studios, 1 June 2019 (R)

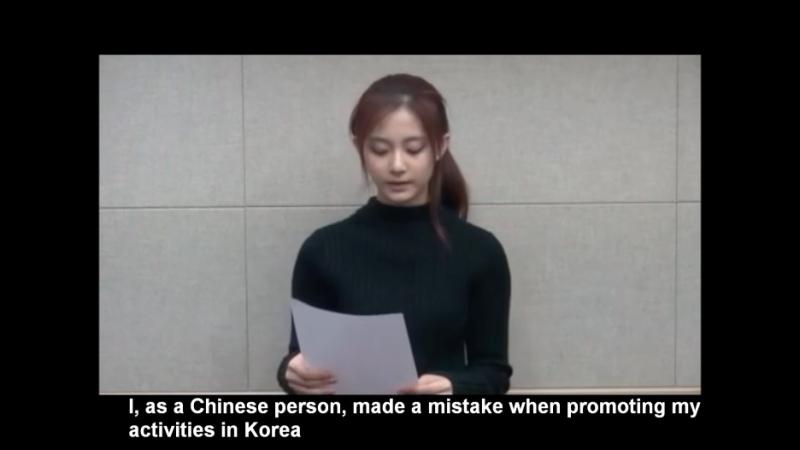

Since the 2000s, K-pop companies have aimed for the Chinese market, with its huge middle class. However, K-pop companies cannot afford to run afoul of nationalistic youth or Chinese government policies. If they do so, they face mass boycotts and even government bans. A hint of this anger came in 2016 when TWICE, a girl group with members from Korea, Japan and Taiwan broadcast a video segment where members waved the flags of their country. Tzuyu waved a flag of the Republic of China, better known as Taiwan. The problem – China considers Taiwan as a breakaway province. With TWICE facing heavy online criticism from nationalist online users, boycotts, and government blacklisting in China, JYP productions made a somberly dressed and tearful sixteen-year-old Tzuyu apologize.

TWICE member Tzuyu apologizing for waving the Taiwanese flag. Screenshot of 쯔위 사과 설명 (영어) TWICE Tzuyu apology explained (ENG).

Politics again intersected with K-pop in the THAAD controversy of 2017. The US asked the Korean government to station THAAD radars in Korea, to better track and intercept missiles that could come from North Korea. These radars could also peer into China itself, and the Chinese government considered this a threat to national security. As a result, Beijing retaliated against Korean businesses. K-pop acts were unable to appear on Chinese TV, or appear in profitable concerts. Chinese citizens called for a boycott of South Korean tourism and businesses. Lotte Group, which provided land for the radars, had to shut down its stores due to sudden official fire inspections or mass boycotts.

Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) interceptors.

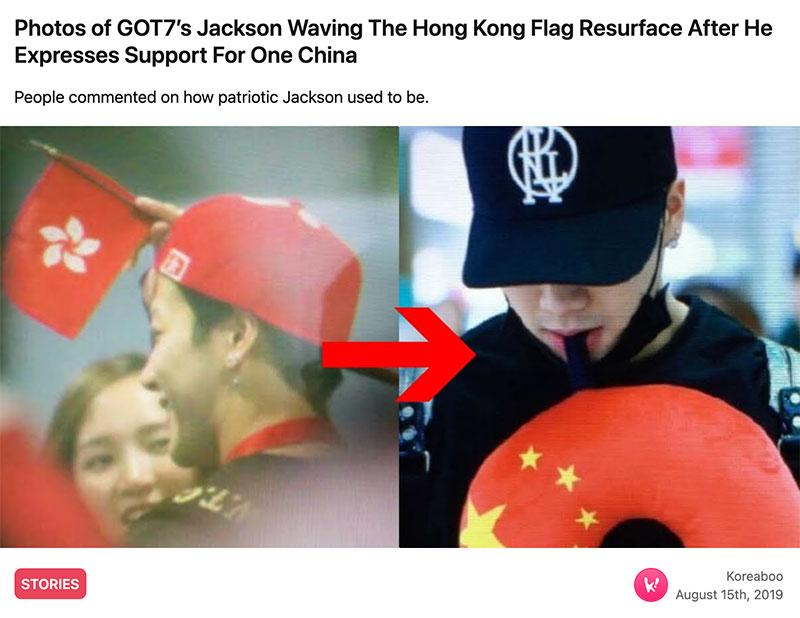

Seeing the bigger profits in the Chinese market, many Chinese members of K-pop acts sought success in China, and took up nationalistic behaviors. Earlier in his career, Wang portrayed himself as a Hong Konger and emphasized his Hong Kong roots. A former fencer who represented Hong Kong in international competitions, he had the Hong Kong flag on his clothes as well as Hong Kong's area code 852.

However, by 2016, Wang began portraying himself as a Chinese artist. When protests opposed to Beiing’s growing influence rocked Hong Kong in March 2019, Wang uploaded a photo of the Chinese flag and declared himself as "one of 1.4 billion guardians of the Chinese flag" on his official Weibo account. This led to criticism from Hong Kong fans who felt betrayed by him. In July, he accepted a Chinese flag from the audience during a concert in Chile, and wore it onstage, proudly shouting, “Call me China man”. These actions earned him praise from Chinese media outlets like Global Times, and Chinese online youth.

Screenshot of Koreaboo article showing Wang’s change from Hong Kong icon to Chinese icon.

As George Gao points out in Foreign Policy (2017), China “...wants to use media as a tool to guide public values in the Leninist tradition, and at the same time hopes to create entertainment products that are well received worldwide.”[1] Wang’s outspoken actions on stage and garish makeup were behaviors common among global pop stars, making him an appealing spokesman for Chinese soft power. However, the Chinese government discourages behaviors like Wang’s. For example, in 2021, the government put a ban on effeminate idols (娘炮 niang pao), a reaction to the androgynous look popularized by K-pop artists. The government criticized "vulgar internet celebrities" and admiration of wealth and celebrity, and yet here was Wang swearing and sipping expensive Hennessey cognac on stage.

Wang thus captured the contradiction of being a national performer in a global genre. He was a perfect representation of the new Chinese generation—strongly nationalistic but also extensively influenced by international popular culture. As the Chinese popular music market grows, will it stay within the lucrative domestic market or expand overseas?

[1] George Gao, “Why Is China So … Uncool?” Foreign Policy, March 8, 2017. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/08/why-is-china-so-uncool-soft-power-beijing-censorship-generation-gap/

Comments

Jackson Wang

Interesting turn around considering he was raised in Hong Kong. He is a contradiction. Lately his antics on stage are pretty questionable.

Add new comment