First posted May 18, 2023 as “‘K’ as Asian America”; Updated March 14, 2025.

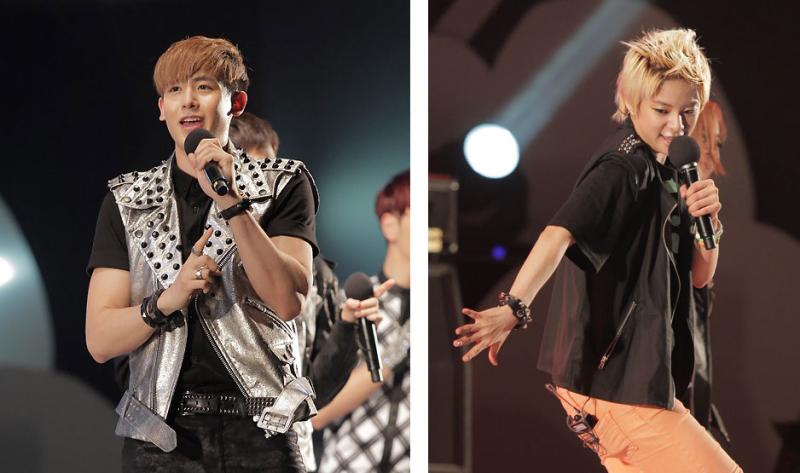

EXP Edition performing on Korean TV

In 2014, Bora Kim, a Korean graduate student in New York’s prestigious Columbia University wondered in her thesis what the true meaning of K-pop is within a transnational context. What would happen if she created a K-pop band composed of non-Koreans? She auditioned six members and labeled the group EXP Edition, short for “experiment.” This group, made up of white performers, would become, in the words of the BBC, “The world’s most controversial 'Korean' band.”

After Kim’s MFA program ended, four of the members decided to try their luck in Korea, undergoing hours of training. Their Korean debut came in the summer of 2017, when they released a music video and performed on a Korean variety show. What followed was a flood of hate from international fans. Some accused the band of cultural appropriation, disrespectfully exploiting Korean culture. Perhaps these criticisms addressed a central question: what is Korean culture, and who gets to determine it?

Following EXP Edition, in 2020, Korean producer Monica Lee created KAACHI, the UK’s first K-pop girl group. With three white members and one mixed race Korean, their debut generated much hate from mostly English-speaking K-pop fans that the comments on their videos were turned off. Facing criticisms of cultural appropriation or insufficient training, this group subsequently broke up.

The criticisms of cultural appropriation by international audiences demonstrates a selective view of who can and cannot perform K-pop. It also demonstrates how even in this increasingly transnational world, Western hegemony shapes our understanding of race, ethnicity, and culture. Groups featuring non-Korean Asians like 2PM, f(x), TWICE, or EXO, did not receive criticism. Lisa Manobol, Thai member of BLACKPINK has become the most-followed K-pop star on Instagram. The group XG, made up of all Japanese members, appeared on Korean TV music shows, speaking in fluent Korean and English. None of them were called out like EXP Edition or KAACHI.

Perhaps, the controversy reveals an unwritten code: non-Koreans in K-pop are acceptable if they are Korean American, part Korean, or recently, Asian. Thus, the “K” in “K-pop” has transformed from describing “Korea” into a term suggesting an Asian song in Korean or English. K-pop reflects this Anglo-Asian fusion culture, with its music, fashions, use of English words and now identity.

Asian: political alliance or ethnic category?

“Asian,” which is a “pan-ethnic” term, lumps together groups with distinct cultural identities. Importantly, it is a Western concept generally not used in Asia. People in Asia did not experience life as a minority in a white world, and so the issues facing Asian Americans, such as economic issues, lack of representation or anti-Asian violence, fail to resonate.

The “K” in K-pop resembles the American concept of “Asian American,” a political term invented by Japanese American Yuji Ichioka and Chinese American Emma Gee in the Third World Liberation Strikes of 1968 at San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley. This term defined an alliance of mainly Chinese American and Japanese American students who fought alongside other groups like the Black Student Union for more diversity and ethnic studies in college.

Asians were previously lumped together as “Orientals” in the 1930s. Student activists repurposed this identity to become a political alliance. Since Asians grew up in the US facing similar issues of racism, poverty, and the Vietnam war, and were also lumped together by the rest of society, it made sense to work together.

.

Asian American protestors at a 2014 protest in New York. Photo source: By Marcela McGreal, CC BY 2.0.

Over time, this term for a political alliance to battle racism and discrimination transformed into a descriptive category for diverse ethnic groups with little in common. Despite the vagueness of the term (did it include Filipinos, South Asians, and people from the Middle East?), it became popularized with the explosion of Asian immigration to the US after law changes in 1965. In the 1980s a new generation of Asian Americans found a common identity with each other, especially on college campuses. Gradually, the term “American” was dropped in popular usage and now the term is often just “Asian” outside of college campuses.

“K” from “Korean American” to Asian panethnicity

While popular perspectives about K-pop from English-speaking audiences suggest that "K" is a representation of Korean culture, its origins derive from disparate locations. By 2010, the “K” in K-pop began to encompass different Asian groups (with Korea at the center of this identity) and represented Asian pop culture with heavy American influences. This is a startling development because the panethnicity of K-pop contrasts with historical movements to keep Korean culture free from foreign influences. One of the reasons for this shift is that Korean Americans popularized K-pop in the 1990s by giving the music an “authentic American” feel. Korean Americans or Koreans who grew up in the US were members of 1990s first generation groups such as H.O.T, Sechs Kies, S.E.S, SOLID, G.O.D, or UPTOWN. Korean Americans such as Tiger JK (Seo Jung-kwon) or Korea Canadian Tablo (Daniel Armand Lee), popularized the Korean hip hop scene in the late 1990s, and Teddy Park (of 1TYM), later produced songs for groups such as 2NE1 and BLACKPINK.

.

Thai American Nichkhun of 2PM and Taiwanese American Amber Liu of f(x) opened the door for non-Korean Asians to perform in K-pop. Photos by 와사비콘텐츠 -, CC BY 2.0 kr and 와사비콘텐츠 - f(x) 에프엑스 서울광장 데니의 뮤직쇼 메가콘서트 피노키오 hot summer by 와사비콘텐츠, CC BY 2.0 kr.

Over time, it became acceptable to have performers from Asian nations perform K-pop. S.E.S (1997), first embodied the pan-Asian concept, being composed of ethnic Koreans from Korea, Japan and Guam. A decade later, 2NE1, debuting in 2009, featured Sandara Park, an ethnic Korean raised in the Philippines. Artists like Thai American Nichkhun Buck Horvejkul of 2PM (2008) and Taiwanese American Amber Liu of f(x) (2009) were not even ethnically Korean.

EXO singing a Chinese version of their hit “Growl” (Páoxiào 咆哮, 2013)

The advantages of having Asian performers to appeal to markets outside Korea became apparent to producers. EXO (2011) used to boast four Chinese members, while Miss A (2010) boasted two. GOT7 (2015) had Chinese American, Thai and Hong Kong members. TWICE (2015), with its three Japanese members, could appeal to the lucrative Japanese market (although a Taiwanese member’s waving of the Taiwanese flag caused political troubles with China). Thus, K-pop provided an alternative to the US market for Asians to become famous internationally.

BABYMONSTER features artists from Korea, Thailand, and Japan

In recent K-pop groups, half or a majority of members are not even Korean. 15 of the 25 members of NCT are from China, Korea, Japan, Thailand, and Asians from the US and Canada. (G)I-DLE boasts a majority of non-Korean members from Thailand, and Greater China. SM Entertainment’s AESPA has Korean, Japanese and Chinese members. YG Entertainment created BABYMONSTER, a Korean-Thai-Japanese group. Half of LE SSERAFIM are from Japan and the US. UNIS, with Japanese and Filipino members, were greeted by cheering crowds during their visits to the Philippines.

K-pop has widened to accept Asian performers and encompasses Asian panethnicity. This identity can be applied to the Anglo settler nations of the Pacific Rim: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the US.

Nearly 1 in 5 Canadians identify as Asian. Asians make up about 15% of the populations of Australia and New Zealand. In the US, Asians are still a small minority at only 6% of the population. But looking at the West coast, Asians make up 15.5% of California’s population and 10.8% of Washington state. In Hawai‘i, taking into account people of mixed Asian background, 57%, or a majority of the population is Asian.

We have now reached a critical mass where it is normalized in these nations to see Asians speaking English fluently. “Asian” identity has also become normalized in these countries.

Conclusion: K-pop beyond panethnicity

Katseye performing with Los Angeles Rams cheerleaders at the 2024 MAMA

In 2020, Billboard launched the “Billboard Global Excl. US chart,” which covers hits of 200 nations excluding the US. If one conceives of the US as a “white” nation (although it is much more diverse with only 59.2% of the population being white) then K-pop parallels the “Global Excl. US chart”.

Mixed race Filipino American singers like Olivia Rodrigo, Bruno Mars, Allan Pineda Lindo (APL.DE.AP of Black Eyed Peas) or Gabriella Sarmiento Wilson (better known as H.E.R) have achieved mainstream success worldwide. These singers, while proud of their Filipino ethnicity, deemphasize it in their marketing, and we know them mainly as American artists. Unlike K-pop artists, they have the advantage of being recognized by their music rather than their ethnicity.

K-pop promotes ethnic identity as a marketing tool. When giving a lecture to students in Jeju, I was asked if I consider the group Katseye to be K-pop. There are no ethnic whites except for Megan (mixed Chinese Singaporean and white from Hawaii), Daniela (Venezuelan American) and Manon (Swiss-Italian-Ghanian). Of the remaining members, Sophia is from the Philippines, Lara is Indian American from Los Angeles, and Yoonchae is from Korea. Their backgrounds are part of their popularity - because they are from ethnicities underrepresented in mainstream American music.

But then, who has the cultural authority to define the “K” in "K-pop"?

Perhaps the worldwide popularity of K-pop comes from it being an alternative to American music. Having a group with mainly white performers, like in EXP, would challenge this alternative space. Most Western non R&B groups are all white, or perhaps with a non-white added in for representation, such as mixed Pakistani-white Zain Javadd "Zayn" Malik from the British-Irish idol group One Direction.

K-pop became an alternative space for Asians marginalized by the US music industry. Thus, it fit well with the panethnic identity of “Asian” and having majority white performers violated this unwritten code of K-pop. This hatred towards groups like EXP and KAACHI risks reproducing the racism that led fans to alternative spaces such as K-pop. What a shame - music is not supposed to divide us. Anyway, let’s hope future groups bring us together instead.

Discussion questions

- How has the meaning of “K” in “K-pop” changed according to the article?

- Why does the article compare this to the idea of being “Asian American”?

- Why are Asian (not just Korean) members like Japanese members of TWICE now accepted in K-pop groups?

- Today, Asians are more visible in places like Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. How might this change how people see K-pop as “Asian” rather than only “Korean”?

- Can you think of an example from your own country or region where a brand or term took on a broader meaning beyond its original identity?

- Why do songs using English or showing different cultures reach more people?

- What does the changing definition of “K-pop” show about cultural identity and globalization?

Add new comment