Transnational K-pop (part 1)

An updated and expanded version of this post (April 26 2024) can be found here.

The charismatic Korean singer Park Jin-young, known by his stage name of JYP, stood in front of potential investors in 2018 to discuss plans for his music company JYP Entertainment. He joked in fluent English that he did not like to do events like this, but his friends told him that if he did, then the stock price of the company would go up. His big announcement ? He was going to assemble a Japanese girl group. This would fulfill his vision for the globalization of K-pop through “globalization by localization.” All the members would be Japanese, but trained in Korea, and the group would be aimed at the Japanese market.

Korean netizens felt reluctant to accept the idea of a K-pop group with all Japanese members. The K-pop blog Koreaboo listed some of the comments from Korean internet users:

- “What do you mean a Japanese group…just take care of the kids you already have….”

- “Just go to Japan and call it J-Pop, don’t wrap it up as a K-Pop to sell it”

- “After suffering so much because of American disease in the past…now it’s Japanese disease? You must have been jealous after watching SM and YG succeed in Japan”

- “They won’t succeed. He must be fooling himself after TWICE succeeded, but an all-Japanese group…”

Regardless of the controversy, NIZIU, as this group was later named, debuted in 2020 after an extensive search of thousands of applicants from eight Japanese cities, Hawai‘i, and Los Angeles and a televised competition show where 26 contestants were whittled down to the final 9 members. NIZIU’s pre-debut single “Make you happy”(2020) topped the Japanese Oricon chart and hit 100 million video streams within 15 weeks of charting on the Japanese hot 100, the fastest female artist to do so. A few months later, they were invited to perform at the prestigious New Year Eve show, the 71st NHK Kōhaku Uta Gassen.[1] Commercial endorsements followed, turning the nine girls into national stars in Japan.

But what the comments from Koreans seem to be asking above is, how does one define K-pop? Perhaps it might be good to examine JYP’s reasoning to come to a definition. He conceived of NIZIU as part of the third stage of “globalization by localization”. The first stage was to export Korean content overseas, like Korean music and dramas. The second stage was to discover foreign talents and mix them with Korean artists. For example, JYP blended Thai American Nickhyun into the group 2PM, which won over Thai audiences. This led to further blending of foreign talent with Korean artists like GOT7, TWICE, and Stray Kids. The phenomenal popularity in Japan of TWICE with its three Japanese members led to the natural progression of making an all-Japanese girl group. In JYP’s own words,this Japanese K-pop group was like TWICE with all Japanese girls.

Unspoken in JYP’s speech was the huge question: why have an all-Japanese group aimed exclusively at Japan? Political relations between Korea and Japan were worsening in 2018. However, his strategy makes sense when considering the Japanese music market, the world’s second largest in 2017 making up roughly 16% of the world’s music market. With K-pop having made inroads in Japan in the 2000s, JYP felt he could better appeal to the lucrative Japanese market if his groups had all Japanese members who embodied the cutesy look popular in Japan.

One could be forgiven for the confusion as to whether this was J-pop, K-pop, or just pop. All the girls (except for Nina, a Japanese American) came from Japan. Yet, three had trained in Korea under JYP and spoke Korean. Their debut video featured Korean locations with small Korean-language signs in the background. They even released a Korean-language version of “Make you happy”. Thus, this was a Japanese group created by JYP working with Sony Music Entertainment Japan, using the appeal of Korea for branding. This group defined the next stage of the diversification of K-pop. Was there such a thing as transnational K-pop? As the Joongang Daily noted:

As K-pop becomes increasingly globalized, it is growing similar to other genres of music like rock, hip-hop and classical music. In the past, K-pop was only created by Korean entertainment companies and sung by Korean artists, but now, it can now be made by anyone in the world, according to their tastes.

A casual fan would face much confusion. On the one hand, K-pop groups BTS and JYP’s TWICE released English language singles and Japanese versions of their songs, some only for the Japanese market, such as BTS’ Japanese-language hit, “Don’t leave me” (2018). Three of four members of YG entertainment’s BLACKPINK boasted international ties. Jennie (Jennie Kim) attended school in New Zealand, while Rosé (Roseanne Park) was a Korean New Zealander. Member Lisa (Lalisa Manobal), from Thailand, released her solo debut song “Lalisa”(2021) in Korean and English. Maybe K-pop singers represent a “brand” more than a musical genre. For example, McDonalds, as an international brand localizes its products, offering shrimp burgers in Japan, bulgogi burgers in Korea, and a spam breakfast set in Hawai‘i.

Then there were groups produced in a K-pop style, and yet identified with a national label. JO1 (pronounced “Jay-oh-one”), an eleven-member boy group, was produced in 2019 for the Japanese market via a joint venture of Japanese and Korean companies. The "J” refers to Japan, while the "O1" refers to the first year of the Reiwa, the Japanese period the group was introduced. This group was formed through a Japanese version of a Korean survival show, in which trainees compete to join the group. Although all members were Japanese, this group trained and recorded in Korea with Korean producers for their first single “Infinity”(2020), giving them a sound and look similar to K-pop groups.

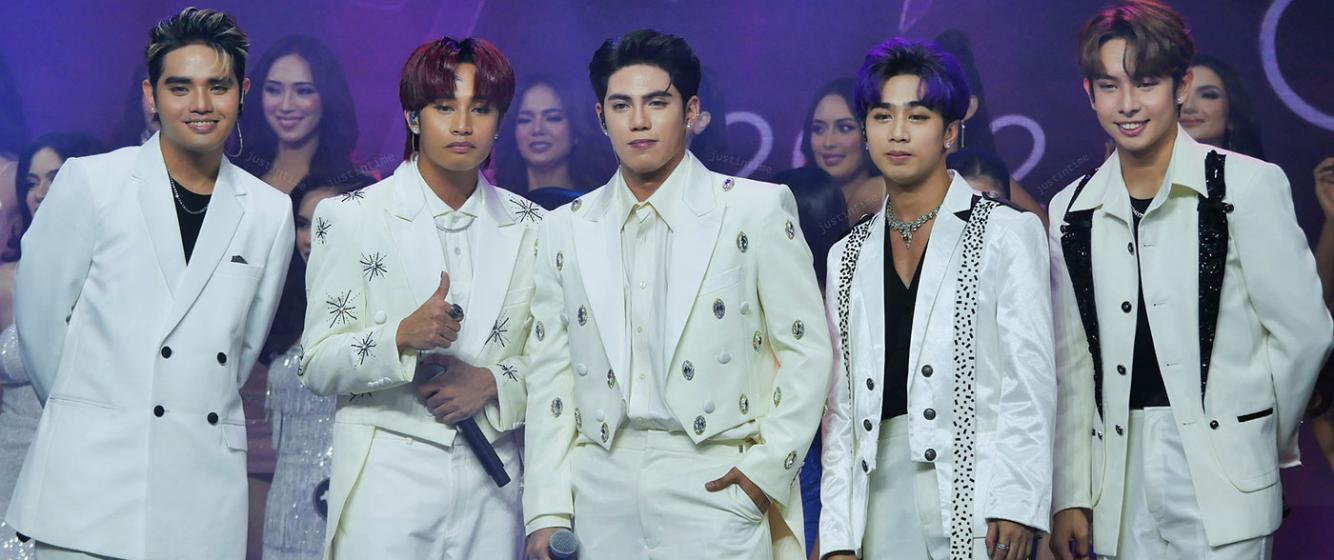

SB19, from the Philippines, further blurs borders. This group was recruited and trained in the Philippines to promote P-pop (Pinoy Pop). Yet, this group is the product of a Korean company, ShowBT Group, founded by Korean Seong Han “Robin” Geong. His goal was to localize K-pop in other Asian markets like the Philippines. SB19 was criticized by some in the Philippines and overseas for trying to be Korean. Their single WYAT (2022) was sung in English and set in a diner like other K-pop videos, but before one calls them a sellout, remember that English is one of the official languages of the Philippines.

Ninety One, a Kazakhstan group created in 2014, also used the K-pop androgynous look of dyed hair, colorful clothes, makeup, and jewelry. They promoted Q-pop, music from Kazakhstan with videos and music similar to a K-pop video. While this may have offended older and rural Kazakhs, Ninety One promoted “Q-pop” (Qazak Pop) as Kazakhstan music, and sang in the Kazakh language to promote its use in everyday life. They gained popularity among urban youth exposed to a multicultural world, yet seeking something Kazakh.

National labels on a transnational phenomenon promotes local identity in a globalizing world. So when a local Hawaii newspaper interviewed me about Hawaii’s version of K-pop group, Crossing Rain, I half-jokingly referred to it as H-pop. It would be an appropriate term since the members were recruited and trained as a group, like other Korean trainees, but they represented the spirit of Hawaii: K-pop style but made in Hawaii, like transnational K-pop all over the world.

[1] "NiziU「Make you happy」ストリーミング累計1億回再生を突破 歴代最速タイ". Billboard Japan. Oct 14, 2023. https://www.billboard-japan.com/d_news/detail/93146/2 Retrieved February 07, 2023.

Add new comment