An updated and expanded version of this post (April 26 2024) can be found here.

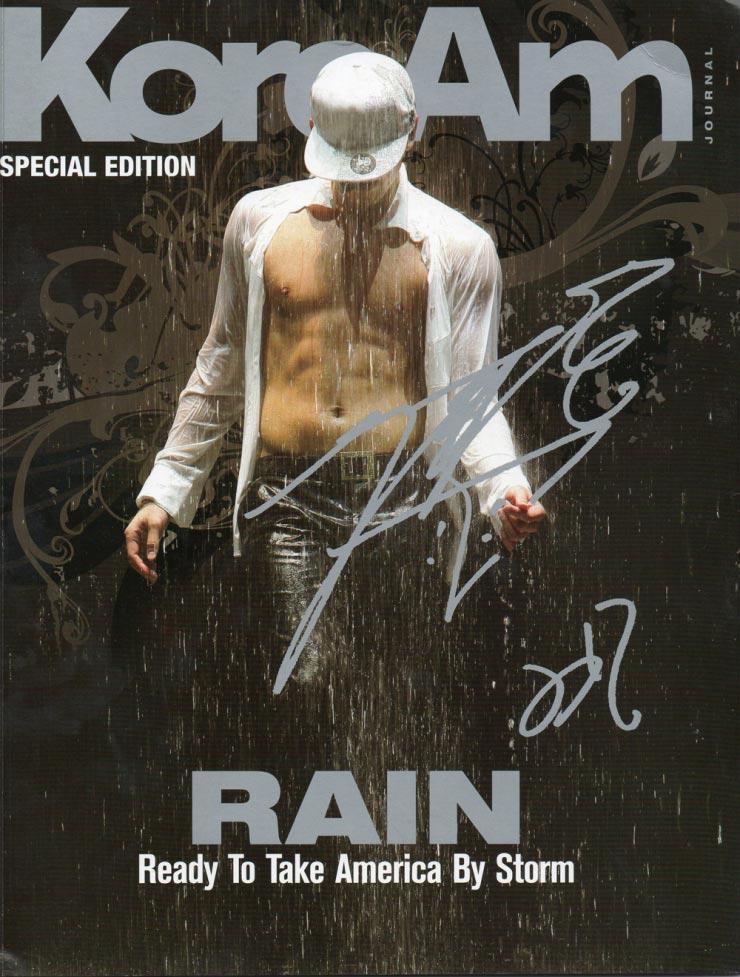

K-pop fans go crazy when a male idol like Rain rips off his shirt to display his rippling “chocolate abs” (six-pack abs) and starts gyrating his hips. Or fans get together to film themselves dancing in public to dances of groups like LE SSERAFIM’s “Fearless” (2022). Or fans in Japan go to karaoke rooms to sing the Japanese versions of songs like BTS’ “'I NEED U (Japanese Ver.)” (2017). These behaviors bear evidence to how J-pop and K-pop had diverged by the 2010s. K-pop was built on the Japanese model in the 1990s, but plowed ahead on its own trajectory in the 2000s with the rise of the digital age. Four key features of K-Pop stand out: visual appeal, synchronized dance, digital engagement, and localization.

First, K-pop is a visual medium meant to be watched, and so videos feature impossibly beautiful idols. While Japanese artists made use of glamorous idols, Korean companies took the visuality of their music to a new level. Male singers like 2 PM, one of the famous “beast idols” of the 2010s proudly showed off their rippling muscles on television, while female singers like Lee Hyori and Hyuna pushed the boundaries of what Korean society then found acceptable through their sexy figures, tight clothing and provocative dances. Korean management companies entrusted much of their songwriting to Scandinavian songwriters (referred to as “The Scandinavian pop machine”), to give K-pop a sleek modern dance sound indistinguishable from their Western counterparts to complement the beautiful idols.

Second, Koreans took dance to a whole new level. Ensemble dance became an integral part of K-pop performance, with idols dancing in unison in complex and perfectly synchronized choreography. Hit songs also had what was called a “dance hook,” a signature move repeatedly performed at key moments in the song. This focus on dance precision requires teamwork and technique honed through hours of brutal practice in the dance studios. In the model used in American entertainment, the talent is discovered by scouts or through auditions. Most young American teens would refuse to subject themselves to years of brutal physical training (with the exception of high school sports athletes). In the J-pop and K-pop models, companies look for kids as young as nine or ten to turn into stars through rigorous training. Thus, the K-pop model demands much from young trainees, since it is so visual and dance focused. While Japanese idols by the 2010s focus on cuteness and accessibility, K-pop requires that its idols dance in perfect precision. Hard work and suffering feature prominently in the narratives of idols as trainees, and fans criticize idols who are seen as being lazy in their dancing.

Third, Korean companies compared to J-pop companies made extensive use of digital media in the 2010s. J-pop companies seemed advanced when related to American companies, because of the Japanese reliance on a wide range of media outlets of magazines, tv shows, movies, and radio to build audiences. Taking it a step further, Korean companies used video sharing sites like YouTube to allow artists to promote their music, interact with fans, and distribute music. Why this change? By the 2010s, digital downloading and piracy made it difficult to generate profits from physical CD and DVD sales. Thus, the Korean companies gave away their music for free online, hoping that publicity from the songs would translate to commercial endorsements, concert sales, merchandise sales, and CD purchases.

In fact, digital fan engagement through social media defines K-pop. Fans could meet through bulletin boards to discuss their favorite idols. Many idols, now constantly post from social media accounts or run live streams from their rooms, creating a sense of closeness with their fans. Also, these fans often give their own time and money to promote the idol, such as purchasing billboards advertisements, gifting bags of rice at concerts, or repeatedly watching their favorite idol's YouTube videos to drive up the number of views. Many fans perform dances of their favorite groups in public and share these videos online. Rather than take down this content, Korean companies saw and still see them as a free promotion for idol groups.

The focus on impossible beauty standards, demands to constantly practice dance moves, and need for extensive digital engagement with fans can cause mental stress to the idols as many are young adults who lack experience in the world outside of trainee life. Every minute detail of their lives is managed by the entertainment companies. On top of that, internet bullying is common, as fans often criticize any idol behavior they find distasteful, such as failing to wear a bra in public. Negative fans, known as “antis” take particular pleasure in attacking vulnerable idols, and this has led to tragic suicides.

This obsession with appearance, overworking, and bullying reflects deeply rooted issues within Korean society. External appearances are extremely important, along with a sense of decorum in one’s public manners, more so than in the U.S. Watch any K-drama and you’ll realize that this is a hierarchical society, where those on the top have extraordinary power over those on the bottom, and bullying is common. One is to put one’s work life ahead of family life through long, hard hours in the workplace. No wonder burnouts and poor mental health as a result of stressful working conditions are so common in Korea. Young fans all over the world can relate to the stresses that the idols feel - they themselves are also in a worldwide neoliberal pressure cooker, even in a “Communist” society like China. Young people, too, engage in digital bullying or criticism, which adds to the fascination they feel with the digital lives of K-pop idols.

A publicity shot of 2PM

Last of all, K-pop localizes their cultural offerings. This reflects the international influences on Korea. While J-pop companies localized to a limited extent by recruiting talent overseas, Koreans took it to a whole new level in the 2000s by including non-Koreans in their groups to increase their overseas appeal. The classic idol group, 2NE1, achieved much popularity in the Philippines because of member Dara (Sandara Park), a Korean who grew up in the Philippines. Thai member Bambam's presence in the group GOT7 contributed to the group's popularity in Thailand. Even songs underwent localization when numerous K-pop groups would release Chinese, Japanese, and English versions of their music. Sometimes, only a Japanese version of a song would be released like KARA’s “Jet coaster love” (2011).

So, K-pop uses dances from around the world. The members often come from outside Korea. The songs can be sung in languages such as English, Japanese, or Chinese. What is Korean about this? Confused? Perhaps we should look at the words of scholar John Lie “...it really says a lot about South Korea. If you think about all the major social and cultural changes that have happened in the last 20 years, (you can see that) K-pop really exemplifies all of that.” Rather than look at stylistic or musical characteristics, the series of blog posts will examine K-pop and J-pop as transnational cultural products, the result of historical interactions between Korea, Japan and the U.S throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. As you will see in my future posts, J-pop reveals a history of Japan coming to terms with the existence of American bases in a defeated nation in the late 1940s and 1950s, issues of a growing consumerist economy in the 1960s to 1980s, and a nation struggling with economic stagnation in the 1990s and beyond. K-pop shows a Korea struggling with the postcolonial issues from liberation from Japanese rule and the establishment of a heavy US military presence in the 1950s, economic growth under a dictatorship in the 1960s to 1980s, and a postdictatorship democracy struggling with issues of generational change.

Add new comment