Scene from Tokyo March. Public Domain. 1929

Tokyo March

Popular songs in early twentieth-century Japan were often battlefields in culture wars of great intensity. At stake was the meaning of Japanese modernity. Nakayama Shimpei and Saijō Yaso’s 1929 best-selling song “Tokyo kōshinkyoku” (Tokyo March) lay smack in the middle of these culture wars. In fact it was at the vanguard of that social change.

One verse of “Tokyo kōshinkyoku” says:

At the romantic Marunouchi Building

Somewhere near that window

There’s a man who’s crying while he writes

The rose he found during rush hour

Reminds him of that girl

“Tokyo kōshinkyoku” arrived only six years after the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923) leveled the city. As Tokyo reconstructed itself, Japan embarked on a new round of modernization. Tokyo became a magnet for migrants coming to improve their prospects. Japan’s famous “salaryman” white-collar workers originated there in the 1920s. The increasing population, a rebuilding boom, and Japan’s new position after World War I meant unprecedented economic growth. The rise of the narikin - the new rich - seemed to move the city in this period. This upper-middle-class avant-garde invested in business. Their children led the modernizing of culture and consumerism of the decade. The song is a Tokyo midsummer night’s dream in images of the modern metropolis as it was seen by these moga (Modern girls) dressed in the latest Western fashions and hairstyles and their mobo (Modern boy) companions.

“Tokyo kōshinkyoku” served as the theme song for a silent movie of the same name. It was also a nostalgic remembrance of the Tokyo of the past. Both film and song were redolent with a sense of loss, and of possibility always at the edges. Lovers pass in the night near the entertainment district of Asakusa. One is on the train and the other on the bus. Asakusa, the old entertainment district, was a source of nostalgia as Ginza became a fashionable Westernized upper-middle-class hangout.

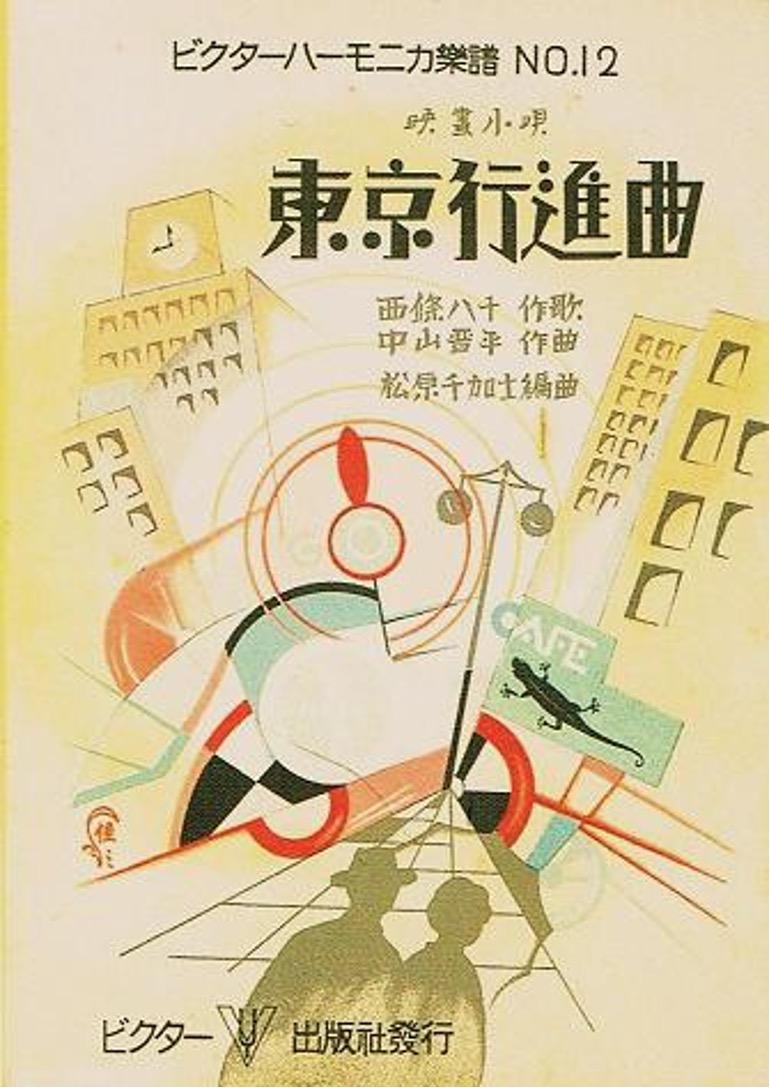

Sheet music for the song “Tōkyō kōshinkyoku (東京行進曲)

The song was unrealistic and dreamy. Most in Tokyo could not live this Westernized middle-class dream. Youth working in the factories or shops for low wages could not afford to tour the city’s various districts and go to movies in far-off Shinjuku. The forlorn lost love of the man in the verse served as a dramatic device for those who could not afford the luxury of letting their emotions rule their working lives. But the desire was there, and the popularity of the song led to real change. The Odakyu department store company, noticing that people called their train to Shinjuku the Odakyu line, decided that would be its name, just as it is in the song.

Social class and the daily reality of sex work for women are dominant themes in the movie and the song. In the film, a factory girl loses her job and becomes a geisha to pay her bills. She meets a wealthy industrialist. He immediately recognizes her as his illegitimate daughter. By chance, she also meets his son and they become engaged. When they learn they are siblings, the wedding is off. In the end, she marries his best friend. She gets the money, but no happiness. The complex reality of Tokyo life before and after the earthquake were the real stars. Saijō Yaso’s lyrics for the song originally even referred to a romantic image of a “long-haired Marxist boy” (this verse did not make the final cut due to government fears of socialist movements among the growing urban working classes).

Reiji Ichiki, Isamu Kosugi and Shizue Natsukawa in the movie Tōkyō kōshinkyoku (東京行進曲) directed by Kenji Mizoguchi , 1929. Oshie marries her brother's friend and leaves for a world tour.

Similarly, Ginza was a new hangout for youth. During its reconstruction, the former attempt at modernizing the district, known as Ginza Bricktown, came down bit by bit. Historians disagree as to how popular the Meiji era (1868-1912) brick town actually was, and even just how much of it was actually made up of Western-style brick buildings - the source of its name - but popular songs refer to its broad sidewalks and exciting nightlife. The newer Ginza stirred memories of the old. Nakayama and Saijō concentrated on that nostalgia. It seems to have complimented their theme of speed, demonstrated with verses about trains and subways. They seemed to be channeling exciting futuristic possibilities of the good life supported by the drudgery and misery of the working class a la Fritz Lange. The trains and buses, hubbub, and love are not taken ipso facto as evidence of happy youth culture. Life is lived for passion, not the other way around.

The Japanese in the first half of the twentieth century thus expressed themselves through the ways in which they created and consumed popular music. Regular people could see themselves in popular culture. They could buy, or not buy, copies of the songs or tickets to the movies. Popular song composers such as Saijō Yaso and Nakayama Shimpei were well aware of this fact. They were in the business of writing songs that evoked dream worlds, but those worlds still had to be recognizable to their listeners. This meant that songs were not simply formulaic representations of working-class or middle-class fantasies. “Tokyo kōshinkyoku” goes on, for example, to say in another verse:

Longing for the past when the streets in Ginza were lined with willow trees

A young beauty becomes a nobody with age

Dance to the jazz music and down liquor into the night

And the rain that is the tears of the dancers will sprinkle at the break of dawn.

This verse provides another example of life imitating art. In the period before the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, the streets of Ginza were lined with willow trees. Some were used as meeting places for friends and lovers. After the earthquake, when Ginza was rebuilt, those willows were removed, and the streets of Ginza were lined with hedges. The song used the image of the willows to evoke nostalgia for the past. In “Ginza no yanagi”(The Ginza willows, 1933) Saijō and Nakayama pulled off the same nostalgic reference again, this time in a song specifically about the trees that also reminded people of both “Tokyo kōshinkyoku” and the pre-earthquake Ginza. In response to the popularity of these songs, the city replanted willow trees along streets in Ginza. Formulaic or not, popular music can have a real effect on culture.

This is visible in popular culture “booms” in which songs supposedly instigated crowd-like behavior. One such boom was a suicide jumper trend that the Tokyo Mainichi Shimbun reported in 1933.

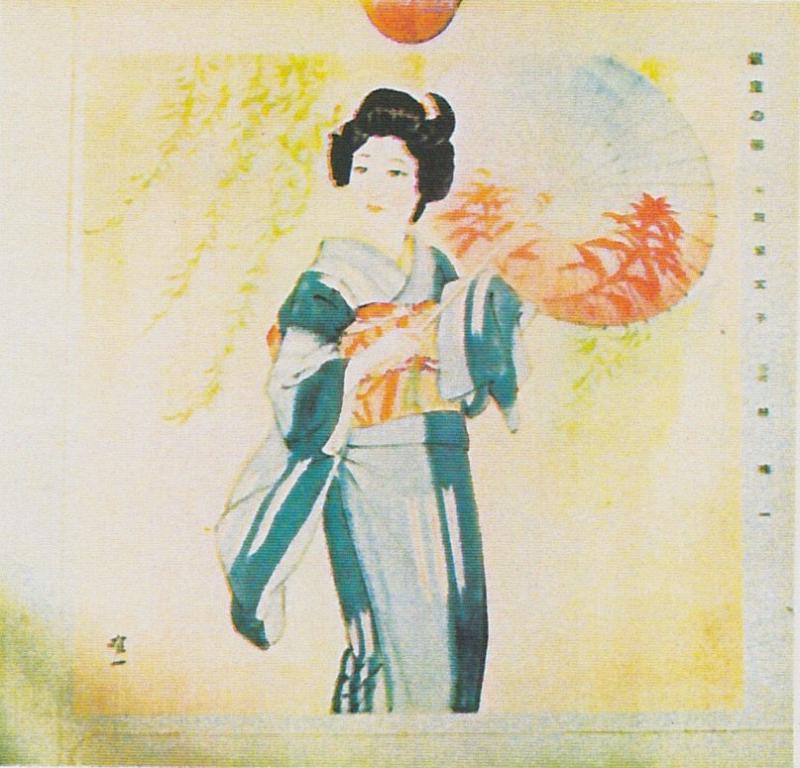

Public Domain.

Record cover for the song Ginza no Yanagi (the willows of Ginza).

On January 9, 1933, a girl student committed suicide by throwing herself into the caldera of Mt. Mihara on Ōshima Island in Izu and this set off a jumping suicide boom. Sixty people successfully committed similar suicides from January into April, and one hundred and sixty attempted such suicides… In February, sales of a popular song called “Kurai nichiyōbi” [Gloomy Sunday] were stopped because it supposedly contributed to a mood of suicides and love suicides.

Whether those who committed suicides listened to “Kurai nichiyōbi” is not clear. The press thought that such a link existed. The song’s distributors removed it from the market (there may have been some police or government pressure). The perception of the power of popular culture is clear.

Patrick Patterson, Music and Words: Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952, New Studies in Modern Japan (Boston: Lexington Books, 2018), 1952. 109-112.

Barbara Hamill Sato, “The Moga Sensation: Perception of the Modan Garu in Japanese Intellectual Circles During the 1920’s,” Gender & History 5, no. 3 (1991): 363–81.

Saburo Sonobe, Nihon Minshū Kayō Shiron (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, 1962).

Saburo Sonobe, Enka Kara Jazu E No Nihonshi (Shokosha, 1954). 358.

Showa Ryūkōkashi (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, n.d.).46.

Add new comment