Skyline of the City of Manila, home of the Manila Sound of the 1970s. CC BY-SA 3.0, Mike Gonzales, June 2009.

Manila Sound and the Roots of Pinoy Pop

Yeah, we gonna go up

Yeah, yeah, we gonna go up

Tanging liwanag ang nakikita

Sa t'wing ipipikit aking mata

Bituin ko'y lalong nagniningning sa dilim

Walang makakapigil

Yeah, we gonna go up

Yeah, yeah, we gonna go up

Only light can be seen

Whenever I close my eyes

My star shines brighter in darkness

No one can stop it

“Go Up” (2019) SB19

SB19 a group from the Philippines sang “Go Up,” much like a K-pop group. In their video, the members dance in precise K-pop style formation on a high-rise rooftop. But they sing in a mixture of Tagalog and English lyrics.

Producers designed SB19 to resemble a K-pop group but tap into Filipino pride. A Korean company, Show BT, selected the members from hundreds of auditioners and trained them to promote a Filipino version of K-pop, known as P-pop (Pinoy Pop).

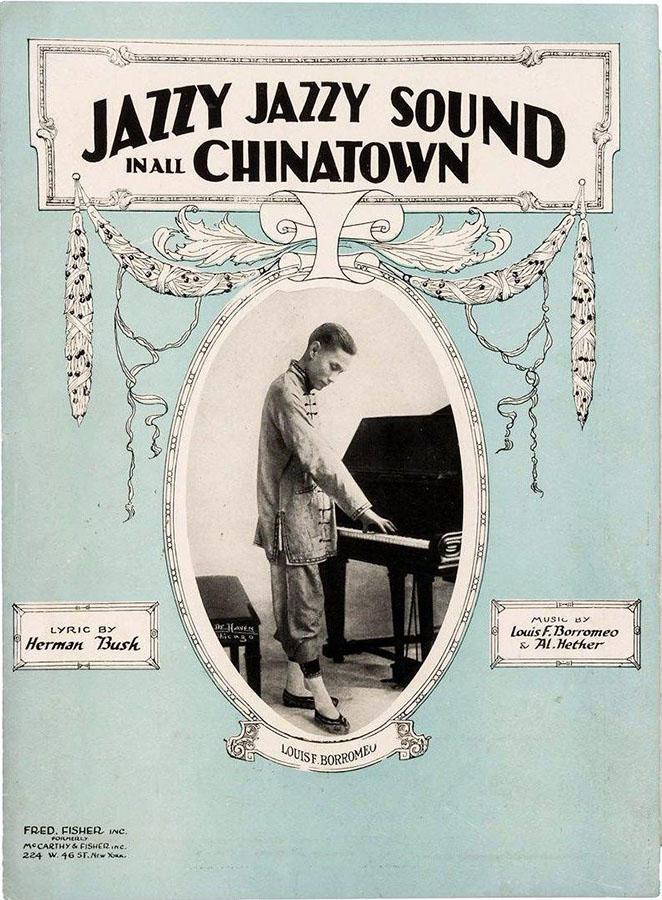

"Jazzy Jazzy Sound in All Chinatown," by Louis Borromeo (featured in cover wearing a costume).

So, is P-pop a recent phenomenon that brings the Philippines into the wider world?

Historically, the Philippines has been part of a transpacific culture. as a Spanish colony since the late 16th century, connecting the Americas with Asia. Manila served as a transpacific port connecting Spanish galleons carrying silver from Latin America with Chinese and SE Asian traders. The United States took over the Philippines in the Spanish-American War (1898). Then it crushed indigenous resistance in the brutal Philippine-American War (1899 – 1902) in which over 200,000 Filipinos died. As colonial American nationals, Filipinos did not face immigration barriers like other Asians, and were able to learn jazz in the US, and played for hotel and ocean-liner orchestras in port cities. They helped spread jazz to Japan. Filipino musicians helped advance jazz worldwide. Musicians like Borromeo Lou played in jazz bands in the US, while Filipino jazz bands spread the music to cities like Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Tokyo.

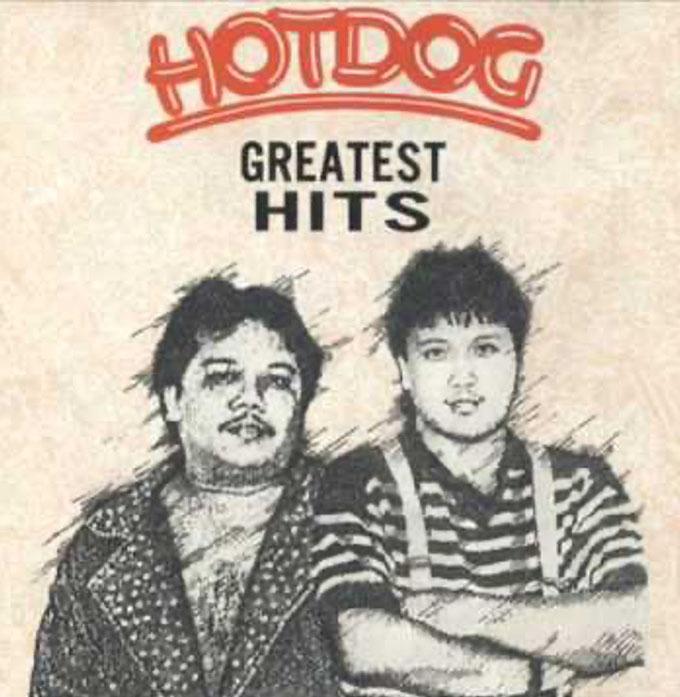

Hotdog, pioneer of the Manila Sound. Screenshot from Marco Aldenese, “Hotdog – Manila”

Although the Philippines became independent in 1946, Filipinos, like postwar Koreans and Japanese, continued to embrace American culture because of US bases and economic ties. American-influenced popular music that developed in the 1970s was dubbed the ‘Manila Sound.’ Dennis and Rene Garcia of the band Hotdog pioneered it in "Ikaw ang Miss Universe ng Buhay Ko" (You're The Miss Universe of my Life, 1974). This genre flourished from the mid to late 1970s combining Filipino sounds with rock and roll, disco, jazz, and funk.

After President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on September 23, 1972, he and wife Imelda sponsored music to distract public attention from the military takeover. These political events were led by Imelda Marcos' singing performances. Her singing was part of a narrative constructed during martial law. Ferdinand Marcos played the strongman while Imelda played the beautiful muse. Filipinos love performances and whenever Imelda performed during political rallies, this created positive feelings for the audiences.

Public domain photograph.

The Marcoses at a ceremony in 1979.

The Marcoses sponsored events like the Manila Film Festival (now Metro Manila Film Festival or MMFF), or the Metro Manila Pop Music Festival. The Beatles performed in the Philippines, but their snubbing of a Marcos breakfast party led to their harassment while leaving the country. The Manila Sound flourished with support from the Marcos government, reflecting the convoluted relationship between music and politics in the Philippines. Hotdog’s song about Miss Universe came out after Filipina Margarita Moran won the Miss Universe pageant in 1973, and during the excitement over Manila hosting a major international event like the Miss Universe pageant in 1974.

Yet, music was also a vital avenue to express dissent during martial law, despite government censorship and threat of arrest. For example, Heber Bartolome's "Oy utol, buto't balat ka na'y natutulog ka pa" ("Hey brother, you are skin and bones yet you are still sleeping," 1975), starts out with these lyrics:

Masdan nyo ang ating paligid, (Observe our surroundings)

akala mo'y walang ligalig. (you think no danger exists)

May saya at mayroong awit, (there's gaiety and song)

ngunit may namimilipit at siya'y humihibi (but someone is wrenching and crying in pain).

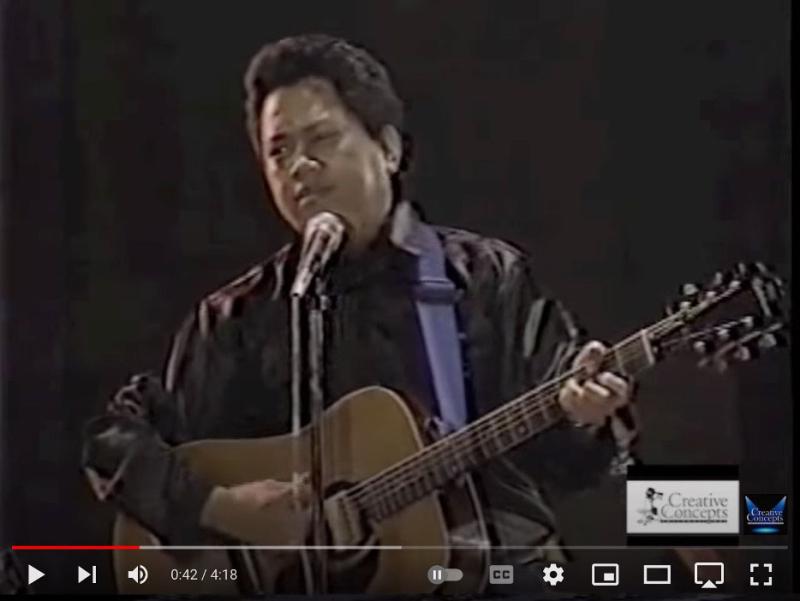

Herber Bartolome Screenshot of Creative Concepts Intl, “EDSA 4th | "Tayo'y Mga Pinoy" Heber Bartolome ✝️🙏 R.I.P. (11/15/21)”

Songs by Heber Bartolome and other dissident artists were appreciated by people already critical of the regime, even though these songs were not supported through government funding and festivals. For example, “Oy Utol” became a frequently requested song on radio station DZRJ-AM. Additionally, Jess Santiago's "Huling Balita" (Latest News) focused on the warrantless arrests, extrajudicial killings, and the desaparecidos (the disappeared) of the Marcos Regime. The 1928 song "Bayan Ko," revived by Freddie Aguilar in the 1970s, was among the movies, tv, and songs banned because of their revolutionary messages.

The Manila Sound preceded OPM (Original Pilipino Music), music composed by Filipino artists of various genres. The Manila Sound also belonged to a late 1960s and early 1970s Pacific movement to localize western music like rock or folk. Rather than doing covers of Western songs, Korean rockers like Shin Joong Hyun or Japanese rock group Happy End played original compositions with lyrics in their native languages.

Similarly, Filipino artists infused their own language into the music. The Manila Sound represented an awakening of cultural pride. As Filipino musician Moy Ortiz noted:

Before the Manila sound, there was a segment of Philippine society…that looked down on the original Filipino pop music. It was once considered badoi (low class)…. Suddenly it became acceptable to the middle class and the educated and even to some members of the elite….[S]uddenly singing Tagalog or Taglish or listening to Filipino songs or Filipino artists became cool…so as a collective we finally embraced our own stories, our own Pinoy sound unapologetically, no excuses, no disclaimers.[1]

Moy Ortiz of The Company giving a lecture on the Manila Sound. Screenshot of Intramuros Administration, “ILS Episode 37: The Nostalgia of Manila Sound.”

Ortiz points out that he was not living in Manila when this sound exploded on radio and television. Instead, these original Filipino-made and Filipino-performed songs had made it to his province. Thus, the hits of Manila sound were actually national hits.

The Philippines has always been part of a Pacific Sphere, both spreading and indigenizing Western cultural trends. SB19’s use of Korean style-pop reveals Korea’s role as a center of cultural production influencing the Philippines. Yet, the Philippines influenced the formation of an Asian jazz sphere. SB19’s sound, like the Manila Sound, adapts global music to local culture to celebrate national identity. Perhaps SB19’s song “Go up” refers to the rise of the Philippines as a center of cultural production.

Mylene T. De Guzman is an Assistant Professor in the University of the Philippines – Diliman Department of Geography. She is currently a PhD student under the Media and Communications program in the Media School, Hallym University, South Korea, where she intends to investigate the digital geographies of KPop fandom.

[1] Intramuros Administration, “ILS Episode 37: The Nostalgia of Manila Sound,” YouTube Video, 44:44, November 20, 2020, https://youtu.be/wOGzx-nejm4

Discussion Questions

- What is the Manila Sound, and when did it become popular in the Philippines?

- What does P-pop mean, and how is SB19 connected to this?

- Who are some early artists or songs mentioned as part of the Manila Sound?

- Why did Manila Sound become more acceptable among middle and upper classes, educated people, and even the elite? What changed in society to allow this shift?

- How did political events (like martial law under Marcos) influence the kinds of music produced or supported in the Philippines during Manila Sound’s era?

- How might modern artists like SB19 or BINI build on the legacy of Manila Sound to reach global audiences, while still keeping a local Filipino identity?

- What does the rise of Manila Sound teach you about how music can be a tool for cultural pride and identity?

Add new comment