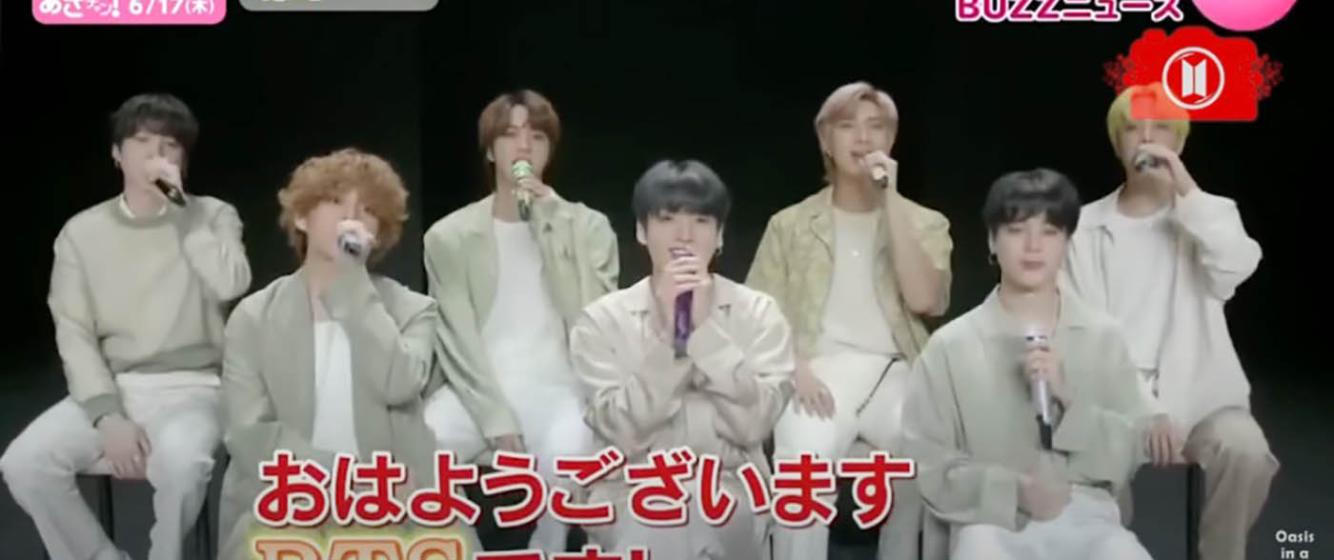

BTS on Japanese TV (posted on “Oasis in a Desert’s” Youtube account). Early in their careers, BTS regularly appeared on Japanese TV, performed in Japan and released Japanese versions of their hits.

Languages of the Pop Pacific (part 3) - Japanese

In karaoke rooms throughout Japan, there is a way for teenagers and young adults to sing K-pop hits despite being unable to speak in Korean – sing the Japanese version of the song. Along with the rise of K-pop in Japan in the late 2000s came the ubiquitous “Japanese version” of K-pop songs.

For example, BTS has released an extensive discography of Japanese songs. Here is a side-by-side comparison of the Japanese music video with the Korean version for “Blood Sweat and Tears”(2016).

And in fact, for BTS fans to know the whole BTS discography, they need to listen to the Japanese releases. “Don’t Leave Me” (2017) was released only in Japanese.

This song was from the album Face Yourself (2018), BTS’s third Japanese studio album, which racked up double platinum sales in Japan.

Other major groups like BLACKPINK, IVE, LE SSERAFIM, STRAY KIDS, well, you get the picture, have all released Japanese versions of their songs. Sometimes, their songs are Japan-only releases, and with no Korean-language equivalent.

Alongside English entering into K-pop songs, many of the top K-pop songs are translated and sung in Japanese by the original groups (the “Japanese version”). So, the idea of K-pop standing for music sung in Korean no longer makes sense. While Korean still signifies the “K” in K-pop and English is a common language for K-pop fans worldwide, Japanese is a hidden third language of the Pop Pacific.

So all this begs the question, why so many “Japanese version” releases in “K”-pop?

_

“Tuition” (1940) shows how Korean students were made to learn and speak Japanese in the classroom. This forced assimilation has made Japanese a problematic language in Korea

Historical problems of Japanese in Korean pop culture

Japanese is one of the problematic languages in K-pop, and reflects the complex history between the two nations, colored by 35 years of Japanese colonial rule over Korea. During this time, Japanese became an official government language. Japanese colonial policy after the March First nationalist protests for Korean independence in 1919 allowed some limited space for Korean radio broadcasts and newspapers, but the colonial government sought to eventually assimilate Koreans into Japanese culture. With wartime pressures, by 1940, the government accelerated a forced assimilation program and prohibited the use of Korean in schools, government or the media. Koreans were heavily pressured to change their names to Japanese names, if they were to access government services. It is this ruthless period of forced cultural assimilation that Koreans remember the most of Japanese rule.

After Korea was liberated from Japanese rule in 1945, the situation reversed. Japanese now became taboo, much like how Korean had become taboo during the last years of colonial rule. The Korean government enacted a ban on Japanese popular culture, and Japanese language broadcasts. Even after a loosening of restrictions in 1998, it is still forbidden to play Japanese language broadcasts on Korean terrestrial television broadcasts.

Rise of the “Japanese versions”

Money speaks louder than nationalism, and the 2000s saw an explosion of “Japanese version” K-pop songs. The Korean government sponsored a push to export Korean popular culture after the 1997 IMF crisis in order to generate revenues for the nation. Korean pop music companies, doing their part for Korea, aimed at the lucrative Japanese market, the world’s second largest. After all, the Korean market was only one tenth the size of Japan’s market. SM Entertainment groomed second generation K-pop singers such as BoA or DBSK for Japanese consumption by teaching them Japanese language and manners. In 2000, the thirteen-year-old singer BoA, who was trained for two years to sing and speak in Japanese, successfully debuted in Japan as a partnership between SM and Japan’s Avex Group. Listen to her hit “Listen to my heart” (2000) sung wholly in Japanese.

Just ten years after BoA’s debut, K-pop artists surged in popularity in Japan through streaming services such as YouTube. They were not trained for the Japanese market, but they could easily broadcast translated songs to Japan via streaming services. Given the grammatical similarity between Japanese and Korean, it was fairly easy (compared to English) to translate Korean lyrics into Japanese. Thus came the birth of the “Japanese version” of songs.

KARA started this trend of “Japanese version” K-pop songs. Originally a mid-level Korean group, KARA debuted in Japan with “Mister” (2010), a translated song with a video produced for the Japanese market that featured KARA confidently dancing and gyrating their hips to the camera.

KARA radiated a sexiness and confidence that had disappeared from J-pop female singers. Their image as strong, confident women unleashed a tidal wave of translated “Japanese version” K-pop songs. Sonyeo Sidae (소녀시대), known as Girls Generation in the West, translated their name into “Shōjo Jidai,” the Japanese reading of the Chinese characters 少女時代that made up their name. Their Japanese version of “Gee” (2011) set over an edited version of their Korean video, helped them to attain popularity in Japan.

More Japanese version K-pop songs followed from numerous artists. BIGBANG achieved success with Japanese language versions of their songs, like “Fantastic Baby (Japanese ver.)” (2012)

TWICE further boosted the popularity of Japanese versions songs by starting a trend of having Japanese members in groups. Three of the nine members of TWICE were Japanese, and young girls in Japan who watched the group could imagine themselves as K-pop singers while singing Japanese versions of their songs. Beside Japanese versions of their songs, TWICE also made Japan-only releases. “BDZ” (2018) was designed for the Japanese market and there is no Korean language version of this song.

Following in TWICE’s precedent, many of the popular girl groups today like LE SSERRAFIM or IVE have Japanese members, to play into young Japanese girls’ fantasies that they too could become a K-pop star if they trained hard. LE SSERAFIM, which has two Japanese members, made a completely new video for “FEARLESS -Japanese ver.-” (2023).

Thus many K-pop songs have Japanese versions, and recently, many groups have Japanese members. What does this tell you about the Japanese market for K-pop?

Role of the Japanese market

_

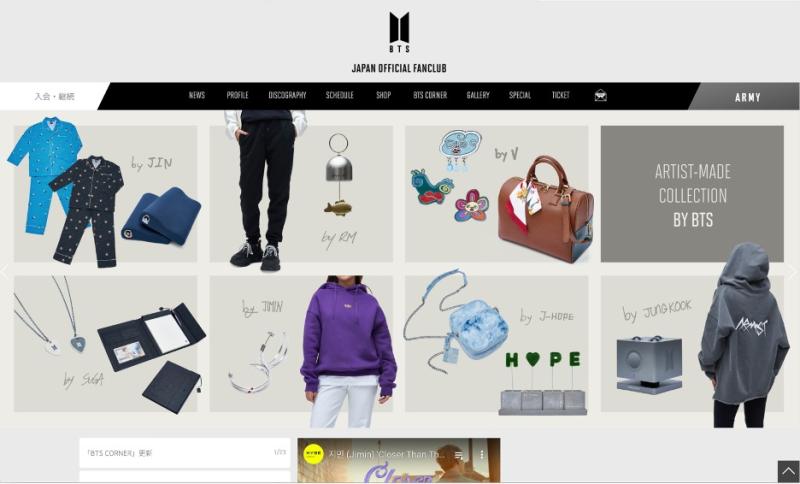

BTS is so popular in Japan, that they have an official Japanese fan club separate from the BTS Global Official Fanclub. (screenshot of BTS Japan Official Fanclub)

Given the size of the Japanese market compared to the rest of the Asian market, one could say that Japanese became an unofficial language of the Pop Pacific through the Korean wave. Interestingly, in Japan both Korean and Japanese versions coexisted to propel K-pop’s popularity. I spoke to several young Japanese women in the mid-2010s, and they told me that the Korean version was the “real” version of the song that they played at school with friends, but the Japanese version was for singing at karaoke. Korean was the language that gave K-pop prestige, while Japanese was the language that generated revenues and financed the production of the Korean wave.

While concert tours to North America, Europe or Southeast Asia have grown in number, the Japanese concert circuit is still reasonably profitable. Japanese fans are devoted and spend a lot of money on expensive concert tickets and merchandise. Japanese grammar is similar to Korean, and a Korean can become reasonably conversant in Japanese with a year of intensive study. When BTS first appeared on American TV, only leader RM could confidently understand and speak in English with other members speaking in short English sentences. But on Japanese TV, most BTS members could speak in Japanese.

The Japanese market is so lucrative for BTS that there are two official BTS fan clubs: a world fan club, and a separate Japan-only official fan club where one can buy Japan-only merchandise. There is not even a separate Korean or American fan club for BTS, just a BTS Global Official Fanclub.

Conclusion: Japanese as a language of the Pop Pacific

With worldwide success, BTS released English language singles, performed in the US, and stopped their concert appearances in Japan before going on a hiatus for members to do their obligatory military service. One Japanese BTS academic fan wistfully told me that many Japanese fans like her felt used, and that BTS forgot their Japanese fans once they became world famous.

But this does not mean the end of Japanese versions of K-pop songs. Other groups are more than willing to take their place, and use Japan to help springboard them into world fame. Although as of 2024, the Japanese yen has weakened considerably cutting into profits, K-pop groups continue to aim at the Japanese market. Groups like SEVENTEEN, despite featuring no Japanese members, have Japanese-only releases, such as “Not Alone" (ひとりじゃない, 2021), which hit platinum on the Japanese charts.

So, K-pop groups regularly release Japanese language versions of their songs and often Japanese-only singles. These songs helped to spread the popularity of K-pop in Japan, still one of the world’s biggest music markets. Yet, these groups are forbidden by law to perform these Japanese-language songs on Korean TV broadcasts on major stations. Thus we have a strange dynamic in the Pop Pacific, which reflects the convoluted relationship between Japan and Korea. Pop culture is more than just entertainment but reflects a deeper history.

Discussion Questions

- Why do K-pop groups make Japanese versions of their songs?

- Why was the use of the Japanese language avoided in Korea historically?

- Why does the article describe Japanese as a “hidden third language” of the Pop Pacific? Why do so many K-pop songs have “Japanese versions”?

- Can you name a song or show from your culture that uses a language with historical difficulties?

- What does including Japanese alongside Korean and English in K-pop tell us about globalization and cultural negotiation?

Add new comment