Kasagi Shizuko’s performance of “Jungle Boogie” in Drunken Angel (Kurosawa, 1948)

Kasagi Shizuko, Tokyo Boogie Woogie and the Reinvention of Post War Japanese Popular Culture

Tokyo boogie woogie, a cheerful rhythm

Makes the heart throb and excited

Resounding across the ocean, Tokyo boogie woogie

The boogie dance is the world’s dance

The burning heart’s song in a sweet singing voice of love

Dancing with you tonight again, under the moon

Tokyo boogie woogie, a cheerful rhythm

Makes the heart throb and excited

This era’s song, the heart’s song, Tokyo boogie woogie

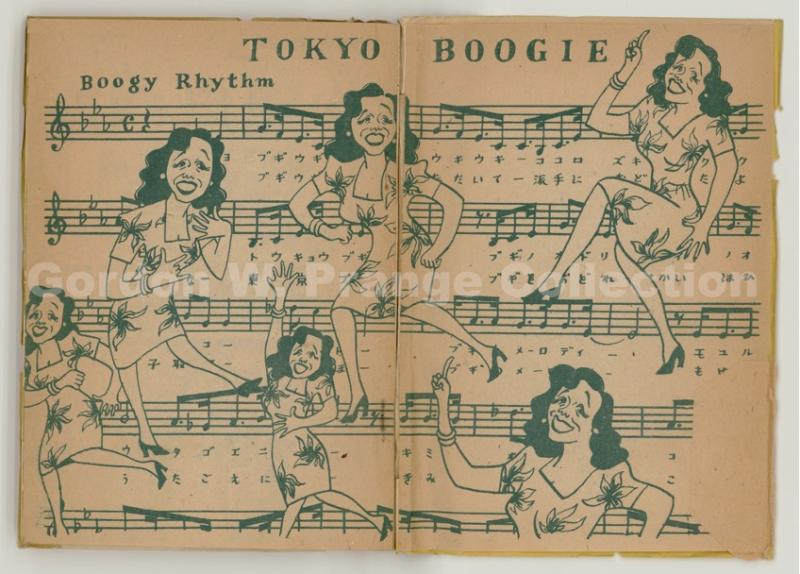

Tokyo Boogie Woogie (1947)

Kasagi Shizuko (1914 – 1985) is renowned for her energetic performances of jazz-influenced “boogie-woogie” songs composed by Hattori Ryōichi (1907-1993). These songs, legendary for “cheering up” the Japanese population in the devastation of the immediate post-war years, made Kasagi a household name. Today, a younger demographic knows only her most famous song “Tokyo Boogie Woogie,” largely through cover versions. What a shame because the story of how a farm girl became Kasagi Shizuko, Queen of Boogie Woogie, is also the story of how women of her generation confronted the challenges of the war and beliefs about women’s place and behavior.

Early career

Born Kamei Shizuko in August 1914 in rural Shikoku as the illegitimate daughter of a seventeen-year-old heir to a landowning family, she was adopted by a friend of her teenage mother in Osaka. Despite the circumstance of her adoption, the young Shizuko would experience a warm upbringing and was a favorite of customers in her parents’ public bathhouse, often performing for them on a makeshift stage in the dressing room and taking traditional dance lessons.

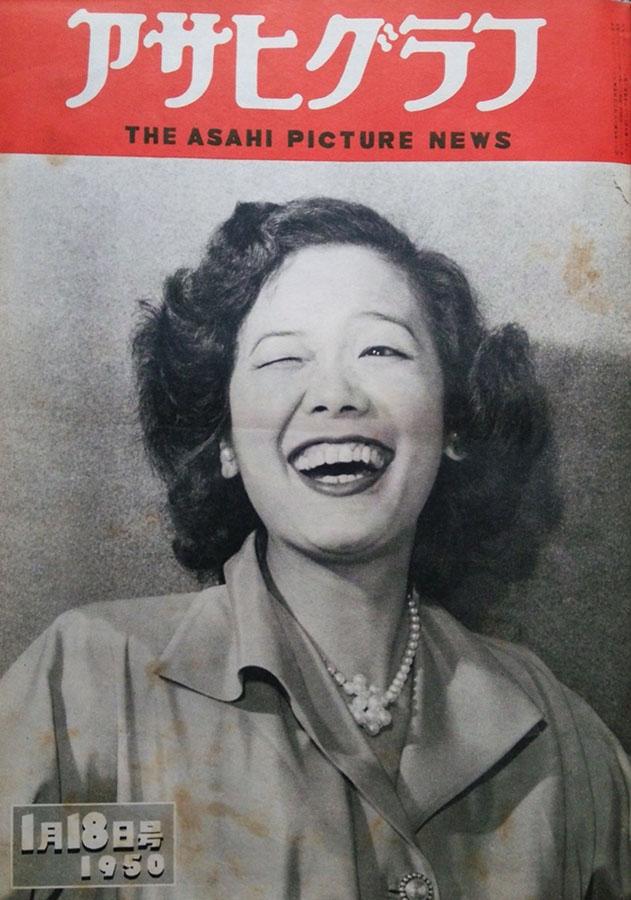

Kasagi Shizuko on the cover of Asahi Graph, Jan 18, 1950

Like many young rural women, Kasagi escaped to the urban areas to pursue her dreams. An accomplished dancer by the time of her graduation from elementary school, she would audition for the upscale Takarazuka Opera, an organization that promoted itself as a training school in the arts for middle-class girls with a good family background. Despite passing all the entrance tests, she was rejected because of her diminutive body size. Undeterred and with support from her adoptive family, she talked her way into a trainee position in the Shochiku Music and Drama Club, the more downscale Osakan rival to the Takarazuka girls dancing and entertainment troupe. In August 1928, under the stage name Mikasa Shizuko, the talented fourteen-year-old was given the chance to appear on stage with the newly formed Asakusa (Tokyo) branch of the dance troupe, where she made friends with other recruits who would go on to become famous entertainers.

The troupe was reorganized in 1934 as the Osaka Shōchiku Girls Opera Company (Osaka Shōchiku Shōjo Kagekidan). It moved away from mixing western and traditional dance and singing styles and instead adopted a much more Americanized delivery built around exuberant tap dance routines, jazz-influenced songs, and a focus on individual stars. This evolution clearly suited Kasagi’s developing vocal style and on-stage performance persona and by late 1933, she was ranked among the top ten stars of the troupe.

Prewar Japanese jazz diva

Still, Kasagi remained largely unknown during the mid-1930s, eclipsed by other stars. In April 1938 she got her big break when she was selected to join the Shōchiku Gakugekidan, a variety theater troupe based in Tokyo. Here, Kasagi met upcoming composer Hattori Ryōichi, who noticed the diminutive singer’s powerful voice and untamed dancing style. According to his account, Hattori was taken aback by the way in which the sickly-looking Kasagi transformed herself once on stage. Wearing high heels and 3-centimeter false eyelashes, the diminutive Kansai- accented singer showcased an energetic and untamed dancing style fused with skills honed in the tough world of Osaka’s entertainment business. These, as well as her unique rhythmic phrasing, marked her as a potential vehicle for Hattori’s interest in incorporating elements of the swing jazz style that had swept the United States two years earlier.

Kasagi with her daughter

Within months, he concluded that the Kansai-accented singer was best equipped to be a vehicle for his dream of creating a Japanese version of the American swing jazz style. Inspired by his new muse he composed “Rappa to Musume” (Trumpet and a Girl, 1939) for Kasagi, encouraging her use of scat-style singing for the first time in Japanese music history. The record, regarded by enthusiasts as the best jazz recording of the pre-war era, led the media to proclaim Kasagi "Queen of Swing.” In the next two years, she would have numerous hits with songs such as “Sentimental Dinah” and “St Louis Blues.”

Tribulations of the war

By 1940, however, the wartime political situation and government crackdown on what was seen as decadent western jazz derailed the trajectory of both of their careers with Kasagi effectively being banned from dancing and singing jazz music by local authorities. Like Hattori, Kasagi would hunker down during the war years, reluctantly singing patriotic or Japanese folk songs for workers in factories. The one bright spot in this period of her life, one in which her brother died in the war, was an unexpected relationship with a fan, Waseda University student Yoshimoto Eisuke. Nine years her junior, Yoshimoto was the oldest son of Yoshimoto Sei, the widowed wife of the founder of the Osaka-based Yoshimoto Kōgyō entertainment agency. Not surprisingly, the highly unconventional relationship was opposed by Yoshimoto’s powerful mother but in 1945, because of both of them losing their accommodation in the firebombing, the couple began to live together. Despite the many hardships of in the period following the war in 1945-46, Kasagi would later call her short time with her lover as the happiest time of her life and in October 1946, with her career beginning to revive, she became pregnant.

Icon of the disadvantaged in Postwar Japan

The couple’s happiness would be cruelly curtailed, however, when Eisuke became seriously ill with tuberculosis, dying just weeks before the birth of her daughter Eiko. Not surprisingly the depressed entertainer considered retiring from show business and announced her determination to devote her time to raising her daughter as a single mother. Fortunately for Japanese music history, she was encouraged by Hattori and others to continue her career and in a dramatic meeting, Hattori presented the singer with his newest creation, “Tokyo Boogie” a song written explicitly for her.

Recorded in January 1948, the up-tempo optimistic “Tokyo Boogie Woogie” became a major hit. It was recorded in late August 1947 with the Columbia Orchestra in front of a crowd of enthusiastic GIs who had been invited to the recording by the English-speaking lyricist Suzuki Masaru (Sakoguchi 2010: 80- 81). The recording itself was released by Columbia in January 1948 and became a major hit following its adoption by NHK radio in March.

In the next year, during which she appeared and sang in several movies, Kasagi would become perhaps the most widely recognized singer in the country. With her energetic performances striking a chord, she would come to be seen by many women as one who could understand the privations of the post-war world of homelessness, disease and the daily struggles and humiliations of finding food and clothing in the black market.

Drawing of Kasagi superimposed over Tokyo Boogie Oogie (1948)

Among her most loyal admirers was Tokyo’s large community of so-called panpan sex-workers who, having seen Kasagi perform while pregnant, naturally saw the singer as the voice of female emotional resilience and perseverance. They would often, according to Hattori, bring flowers to the stage and effectively acted as an informal fandom (Sakoguchi 2010: 94-98). Kasagi, who openly gave her support to sex worker rehabilitation centers, emerged as the voice of hope for not only these women but for hundreds of thousands of war widows, abandoned and orphaned teenagers, elder sisters taking care of siblings and many others struggling to cope with a world of shortages, black markets, disease, and daily humiliations (Kawaguchi 1996: 51).

Later career as icon of a new postwar Japan

With strong support from the most disadvantaged sectors of immediate post-war urban Japan, Kasagi rebuilt her life and became the voice of Hattori’s dream of a musical expression that could contribute to Japan’s revival. Now free from wartime restrictions, Hattori worked tirelessly to provide his muse with an outpouring of jazz-infused compositions that in combination with her vocal delivery, vibrant dance style, and modest but optimistic demeanor, perfectly matched the country’s mood rejecting the hierarchical, status-based society blamed for the rise of militarism. During 1948-50, he worked tirelessly to provide her with an outpouring of jazz-infused compositions that in combination with her vocal delivery, vibrant dance style, perfectly matched the country’s mood. This included “Jungle Boogie” (1948) which she performed by growling with raw sensual energy in Kurosawa Akira’s movie Yoidore Tenshi (Drunken Angel, Kurosawa, 1948). “Kaimono Boogie” (Shopping Boogie, 1950), sung in the Osaka dialect, was an ode to the postwar craziness of doing daily grocery shopping.

Her musical and performance template would attract imitators. By 1952, Kasagi would find herself increasingly eclipsed by child star Hibari Misora, who would become Japan’s premier solo artist. Her response to this decline in popularity was to reinvent herself as a comedic actress, appearing in several movies alongside Japan’s comedy giant Enoken (Enomoto Ken’ichi) who was among her biggest supporters. In the mid-1950s, Kasagi, now in her forties and no longer the lithe dancer of a decade earlier, essentially retired from performance, concentrating on movies and TV shows while raising her daughter. Although her roles became increasingly small, she was able to boost her flagging career in the 1970s when handed the role of a judge on a popular TV singing show and the main role in a commercials for face soap.

By the time of Kasagi’s death from breast cancer in 1985, her career as a singer was largely unknown to those born in the 1950s and 1960s. After her passing, Kasagi’s life has been commemorated through CD compilations, TV serial dramas, as well as successful stage musicals based on her life. Indeed, it would be safe to say that Kasagi’s transcendent post-war success are now well-enshrined in Japanese popular culture. Her performances and the reaction to them, especially by young women, also gave Kasagi the strength to cope with her personal grief and achieve an unprecedented status as a single mother who embodied the post-war tenacity, resolution, and fortitude of women of her generation.

This blog post is adapted from a longer article by Michael Furmanovsky and Patrick Patterson, “Exploring the Life of Singer Kasagi Shizuko Through NHK's Asadora (Morning Drama) “Boogie Woogie” (2023)"

Works Cited

Hosokawa Shūhei. 2005 “Kasagi Shizuko no suingu suru koe” [Kasagi Shizuko’s Swinging Voice]. 17-36. National Institute of Japanese Literature. https://ronbun.nijl.ac.jp/kokubun/01101153

Hosokawa, Shūhei. 2007. “The Swinging Voice of Kasagi Shizuko: Japanese Jazz Culture in the 1930s.” In Patricia Fister and Hosokawa Shūhei, eds., Japanese Studies Around the World 2006: Research on Art and Music in Japan. Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies, 159-85.

Kawaguchi, Emiko. 1996. “Senji kara sengo e kakete no sensō mibōjin' no seikatsu to ishiki” [Life and Consciousness of War widows during and after the War]. Japan Society of Lifeology. 1: 41- 53.

Sakoguchi, Sanae. 2010. Bugi no jō – Kasagi Shizuko [Shizuko Kasagi: The Boogie Queen]. Gendai Shokan.

Michael Furmanovsky is a Professor of Cultural Studies at Ryukoku University. He teaches classes on American culture and movie history, while also being active in the field of Japanese popular culture. He has written articles on most genres of western popular music in Japan including jazz, country, rockabilly, folk, pop as well as studies of pre- and post-war women's fashion and the Shochiku girls entertainment dance troupes. He can be contacted at mfurmanovsky@gmail.com

Add new comment