Japan's best baseball player of the 1950s was an American from Hawai'i

I am an occasional spectator of baseball. Once upon a time, I was a more avid sports fan, when I needed something to help me kill time. There's no time to kill these days. I've also come to realize few things make me feel more useless than watching other people exert themselves in an athletic contest while I complain about how much my ass and lower back hurt in front of the television. Is it just me, or does anyone else see the irony?

.

I used to be more active. But even then, I had not played baseball. I didn't have the inclination to do so, and by the time I might have had a passing interest in trying, as an older teenager, it was already too late. Baseball fundamentals should be nurtured in childhood. I do watch the game from time to time, and I have an abiding admiration for the freakish talent it takes to play the game, talent I have never had. Like the ability to throw a ball the size of an apple 95 miles an hour. Or being able to hit a ball that size coming at you at that speed with a stick less than three inches in diameter. In high school, I played football and wrestled, and I wrestled in college. That was the extent of my skill set: it's easier to hit other people than a baseball.

I'm nonetheless drawn to the game in some ways. There's a certain aesthetic appeal to the game, something vaguely antique about it. The baseball cap of the mid-20th century period pairs well with an OCBD. And there are pinstripes.

Baseball has a storied mythology, with an origin disputed by scholars. In Hawaiʻi, we have a long history with the game, longer, in fact, than most other places in the United States. One of the founding fathers of the game, Alexander Cartwright, made Hawaiʻi his home. There are those who say Abner Doubleday invented the game, but we know better here. Cartwright, a contemporary of Doubleday's and member of the same New York athletic club, was responsible for some of the key characteristics of baseball. The distance between first and third bases. The three strikes. Alexander Cartwright came west, failed to strike it rich in the 1849 Gold Rush, and decided he would return to New York City going the other way around the world, via China and Europe. He made a stop in Hawaiʻi and never left, becoming King Kalākaua's Fire Chief. He also taught the game of baseball to Hawaiʻi's children.

Part of Cartwright's legacy is the popularity of the game with Japanese immigrants to the islands, largely brought in as labor for the sugar plantations. Baseball was embraced by the Japanese because it was a game which did not require great size or strength, and the Japanese at the time were a diminutive lot. They did not lack in athletic ability or skill, however, and soon became adept at the game.

One such player was a kid from the island of Maui. Kaname Yonamine was born in 1925 in Olowalu to an Okinawan father and a mother from Hiroshima. He sought a high school education on the island of Oʻahu in Honolulu at Wallace Rider Farrington High School. He adopted "Wallace" from the school's name, which soon became "Wally," which became his legal name. While at Farrington High School, Wally Yonamine played both football and baseball, and seemed destined to pursue football as a professional sport. In 1947, he would make the roster for the San Francisco 49ers, then a two-year-old franchise, and became the first Japanese American to play professional football. He played twelve games in a single season for San Francisco, but ended his football career when he injured himself playing baseball in the offseason back home in Hawaiʻi. After playing for a couple of years locally on Oʻahu, Yonamine headed for the U.S. mainland in 1950 and played baseball for the Salt Lake City Bees, the farm club for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. Yonamine turned in strong performances over 123 games, and Lefty O'Doul, the San Francisco Seals manager, suggested to the American occupational forces in Japan that Yonamine play baseball in Japan as a way of easing postwar tensions between Japan and the U.S. A baseball ambassador, both Japanese and American.

.

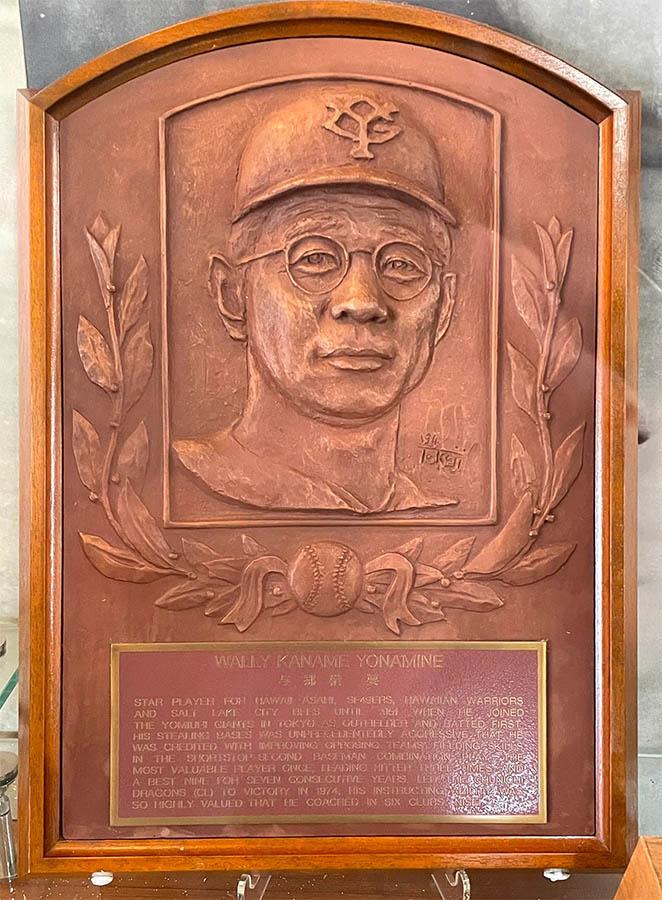

A permanent exhibit—a miniature museum, actually—dedicated to Wally Yonamine in the passenger terminal of the Daniel K. Inouye International Airport in Honolulu.

Maybe the people who organized Yonamine's move to Japan thought he'd be a natural fit because his parents were from Japan. When he arrived, he was anything but. Yonamine, who had grown up playing ball in the U.S., played with a quintessentially American style which rankled Japanese fans. I had erroneously assumed growing up that Japan had somehow "acquired" baseball in the postwar years from occupying U.S. forces. I came to learn eventually that Japan has had baseball almost as long as Hawaiʻi has, having been introduced to the game in the late 1800s, when it became a popular collegiate sport there. They had a different style of play. Japanese runners trotted to first base on a ground ball; Yonamine ran through first basemen to beat the throw. He broke up double plays. He dove for catches in the outfield. Aggressive. American. Angry fans jeered him and threw rocks and bottles. They regarded Yonamine's style of play as "dirty."

Yonamine did not speak Japanese well, though he grew up in a household with parents who were born in Japan. Despite his Japanese name and face, he was regarded as a foreigner. He had been the subject of racist stereotyping among white sports reporters when he played ball on the U.S. mainland. He became the target of anti-foreign sentiment in Japan as an American. He was brought to Japan to bridge a gap, being both Japanese and American. He was to find out that he wasn't both—he was neither.

It's something I've had a taste of myself.

Wally Yonamine would eventually persevere and become a beloved Japan baseball icon through sheer force of will. He would earn the respect of his Yomiuri Giants teammates by staying in the same third-class hotels and riding the same third-class trains they did. He was one of the few players of the time in Japan to sign autographs for fans, including a boy named Sadaharu Oh who would grow up to be a legendary hitter. The accolades he garnered in the 1950s are unmatched by any other player in Japan in the same decade. He won seven consecutive "Best Nine" awards from 1952 to 1958, three batting titles, and the Central League MVP of 1957. His Yomiuri Giants won four championships. Wally Yonamine was Japanese baseball in the 1950s.

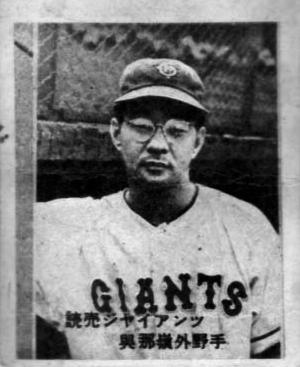

This photograph is in the public domain

Yonamine, as a Yomiuri Giants centerfielder, at the height of his career.

Over time, Japanese players would embrace Yonamine's "dirty" American style of play, and today Japanese players are just as aggressive on the field as their American counterparts. He would go on to have a successful career as a professional manager. After his baseball management career ended in the late 1980s, he would split time between Los Angeles and Japan running a pearl business with his wife.

I've spent several hours researching baseball in Hawaiʻi in its territorial period and have started to research baseball in Japan in the postwar period in preparation for the manuscript I'm currently working on, which sends my detective to Japan in 1955 in search of a fugitive. I had seen Wally Yonamine's statistics, but it wasn't until I learned about his life during his early Japanese baseball career that themes emerged that resonated with me, themes I could identify with personally. Themes that are shaping the novel as I work on it. As Japanese Americans from Hawaiʻi, we are in many ways culturally stateless individuals, neither Japanese nor American, despite many optimistically believing we are both.

In a way, though, it's special to be neither. We are our own thing.

We just need to run over a first baseman on occasion to remind folks of the fact.

.

Meiji Jingu Stadium in Tokyo, home of the Tokyo Yakult Swallows of the Central League, as seen in July 2025. One of the oldest baseball stadiums in Japan, Meiji Jingu has been around since 1926. It will soon be demolished.

_______________________________________

Scott Kikkawa is a fourth generation Japanese American raised in Hawai'i. Currently a federal law enforcement officer, the New York University alumnus is the author of three noir detective novels set in postwar Honolulu—Kona Winds (2019), Red Dirt (2021), and Char Siu(2023) and numerous other short stories. He can be contacted at scottkikkawa@gmail.com

Discussion Questions

- Yonamine was seen as “neither” American nor Japanese, despite his heritage and upbringing. Have you or someone you know ever experienced this feeling of not fully belonging to a particular group or culture? How did that shape identity or experience?

- Yonamine was expected to act as a bridge between Japan and the U.S., but instead he was treated as an outsider by both. What does his story reveal about how societies treat people with hybrid or transnational identities?

- How does Wally Yonamine’s story show that sports can be both a source of unity and division? Can you think of another example—past or present—where an athlete challenged cultural or racial expectations?

- If you were to write a short article or blog post about a figure—sports, music, or pop culture—who crossed cultural borders like Yonamine did, who would you choose? What personal story or connection would you start with? (and send it to us if you are satisfied with your writing)

Comments

Discussion Questions

Add new comment