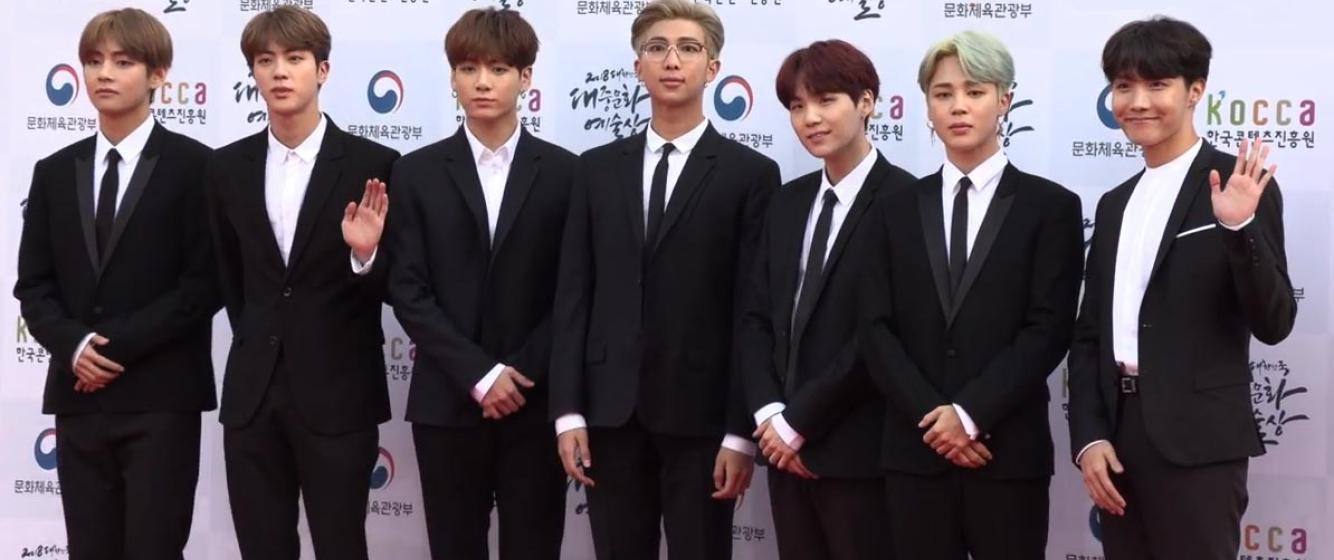

BTS on the red carpet of Korean Popular Culture & Arts Awards on October 24, 2018. By NINE STARS, CC BY 3.0

Introduction to the Pop Pacific - REMIX

(First posted March 9, 2023; Updated March 8, 2024)

Now that we’ve run this blog for a year(!), we will be revisiting and updating older posts. Enjoy!

“K-pop. J-pop. What’s the difference? Is it just that one is from Korea and the other from Japan?”

As a professor who has taught a class on K-pop and J-pop for over ten years, I get asked such questions all the time.

These blog posts focus on the “Pop Pacific,” a space of creation of transnational music like K-pop and J-pop, and media like anime. The ancient Polynesians looked at the Pacific as a path connecting people rather than as a barrier separating them. The same can be said about Korean, Japanese, and American music originating from transpacific contact zones such as Japantowns and Koreatowns in the U.S, cosmopolitan cities in East Asia, or American military bases. Sojourners who traveled across the Pacific, such as Asian Americans, military personnel, or migrants played a key role in this transnational culture.

Here are some stories I tell to explain the Pop Pacific.

First, in 1995, I encountered K-pop when I was a graduate student spending a week in Korea, on a layover from Hawaii to Japan. While walking down a bustling street with friends, I heard a recording of songs like Kim Gun Mo’s “Wrongful Encounter” (Jalmotdoen mannam 잘못된 만남 1995) blaring from a street vendor. It sounded like something you would hear in a nightclub, but with incomprehensible lyrics, since I didn’t know any Korean at that time. Tell a Korean friend you like something, and he’ll buy it for you, and I ended up with a handful of Korean music tapes.

Kim Gun Mo’s “Wrongful Encounter” (1995) one of the first K-pop songs I heard.

Later on, I played these for friends and the songs would always elicit their amusement.

“What are you listening to?” they would often ask.

“Korean pop music!” I replied, wondering why people felt amused. Perhaps it wasn’t cool to listen to Korean pop music unless you were Korean. Back then, Korea was considered a place to buy cheap souvenirs, like T-shirts, or expensive commodities such as ginseng at a shop in the tourist district of Insadong, if one visited at all.

Fast forward to 2016, over two decades later, and I am a professor teaching Asian history. A young woman in class excitedly explained to me the appeal of BTS, her favorite K-pop group. In her free time, she was studying lyrics to BTS’s song “Fire” (2016).

Here’s a second K-pop story. When I was in Seoul the following year, I met students who were studying Korean to learn BTS lyrics. I sang in a noraebang (karaoke room) with a German student of Turkish descent. Our song? “Fire.”

And here’s more stories. BTS joined the ranks of international pop stars with their U.S TV debut at the 2017 American Music Awards. Thanks to K-pop, more students are eager to learn about Korean history. Even professors at a BTS academic conference I presented at in 2022 could rattle off BTS trivia with encyclopedic precision– “Suga faced financial hardship and hurt his shoulder as a trainee.” The academics also referred to BTS members by their real names - Yoon-gi, not Suga.

What a stunning change! Only five students signed up for my Modern Korea course in the 2000s, and now professors are K-pop fans! Today, students and writers worldwide view Korea as a land of cool, a place they want to visit. I mainly listen to K-pop while driving to work and started thinking that, maybe, I could write something about my experiences.

J-pop through the Arashi concert in Hawai‘i

News channels focused on the huge numbers of fans that ARASHI brought to Hawaii in 2014, due to lack of public familiarity with the group.

Let me tell you another story of a concert that I went to in 2014. While the K-pop phenomenon exploded globally and its acts became household names worldwide in the 2010s, Japanese popular music, or J-pop, languished in relative obscurity outside Japan. The Japanese idol group Arashi made its U.S debut in Honolulu, Hawai‘i in 2014, to celebrate their 15th anniversary. Their stage was the largest ever erected in Hawai‘i, about 63 feet (19.2 m) tall, 280 feet (85.3 m) wide, and 64 feet (19.5 m) deep. Japanese fans had to pay for a fan club membership and then win a ticket lottery. Winners flew to Hawaii on tour packages ranging from 270,000 to 550,000 yen (equivalent to $2,600 to $5,400). 15,000 Japanese came for Arashi, some on 18 charter flights, pouring $20 million into the local economy. A total of 167 buses – every remaining bus on the island – shuttled concert attendees back-and-forth between Honolulu and the Ko Olina resort. An estimated 100,000 to 160,000 people purchased theater tickets to watch the concert back in Japan. Fortunately, Hawaii residents like me easily purchased tickets online.

By Japanese Station - YouTube – View/save archived versions on archive.org and archive.today, CC BY 3.0.

Arashi in November 2019.

Why all the commotion? As Japan’s most popular boy band (although its members were in their thirties in 2014), Arashi dominated Japan’s Oricon song ranking charts until their hiatus in 2021. This was no small feat, given that the Japanese music market is the world's second largest, making up 20% of the world’s music sales, slightly edged by only the U.S. In terms of money, Arashi was the top artist in Japan in total sales revenue for 2013, making about $138 million dollars, not including revenue from commercials or endorsements. At that time, these sales figures were nearly 65% the size of the entire South Korean music market.

The Arashi concert featured the group descending from the sky on a helicopter.

Yet, puzzled Hawai‘i audiences knew little about Arashi. The local media had to explain who they were, and their popularity. When I stood among the thousands of fans, I was among the handful of non-Japanese in attendance. Two non-Japanese spectators, a mother and her son-in-law whose wife was home taking care of the kids, stood next to me. They received free tickets as an apology to hotel guests for the noise of the concert and asked me who Arashi was, and what all the fuss was about. It was difficult to explain. I told them Arashi seemed to appear daily on Japanese TV dramas, music shows, and commercials. While I was speaking, a helicopter carrying Arashi emerged from the sky, like gods descending from the heavens, and the arena erupted in pandemonium. They landed backstage and when they appeared on the front stage, some fans cried, others screamed. The people I was talking to were still bewildered.

Personal photo by the author (before the concert started)

Arashi stage, Ko Olina, Hawaii September 19, 2014.

This sums up J-pop, a genre relatively unknown outside Japan but comprising much of the world’s second largest music market. In contrast, K-pop from Korea, a relatively small nation of 50 million, has attained worldwide popularity. But what is the historical relationship between K-pop and J-pop?

In the early 1960s, Johnny Kitagawa, a young Japanese-American government worker in Japan, realized the hit formula for entertainment when watching the movie West Side Story: pretty boys who can sing, dance, and act. They would not be the best singers, the best dancers, nor the best actors, but they could do a little of each to appeal to teenage girls. Coming from a time when singers only sang, and dancers only danced, this was a revolutionary development. He founded an entertainment agency, Johnny & Associates, that implemented a training system (based on the US model) for his early groups like Johnny’s or the Four Leaves. By the 2000s, Johnny & Associates became Japan’s most powerful talent agency, and Arashi was one of this agency’s successful idol groups.

However, Matsumoto Jun of Arashi caused a firestorm among Korean fans by suggesting that BTS’ success came from the model developed in Japan by Kitagawa. One of the reasons for the Korean fury over Matsumoto’s comments was Japan’s brutal rule over Korea from 1910 – 1945, when the Japanese colonial government enacted policies of forced assimilation, such as banning Korean language media in the 1940s. This history understandably makes many Koreans loathe to acknowledge Japanese influence. While Koreans made major innovations on Kitagawa’s model, Matsumoto had a point: K-pop and J-pop must be understood in historical relation to each other. Japanese pop music heavily influenced K-pop. Performances by K-pop BTS, or BLACKPINK include recognizable idioms – dancing and singing idol groups and energetic fan chants accompanying stage performances, something familiar in the world of Japanese pop since the 1960s.

Idol group NIZIU represents the fusion of J-pop and K-pop – Japanese singers trained in Korea – and also represents how much these genres have in common.

The influence went both ways in the 20th century. Just as Japanese popular music influenced Korean popular music, Korean music highly influenced Japanese popular music. Koga Masao, one of the godfathers of prewar Japanese music, was inspired by the songs of the Korean workers he heard in colonized Korea. Fast forward to 2024: Korean-trained Japanese idol groups such as NIZIU appear regularly on Japanese TV and K-pop outperformed western music in popularity in Japan, with Western pop only accounting for a mere 0.3 percent of the Billboard Japan Hot 100 chart for 2023, lagging behind K-pop which took up approximately 20 percent.

Personal photo

Author Jayson Chun with BLACKPINK sign, Osaka Japan, Dec 24, 2018.

Therefore, most of the popular music in East Asia really is transnational music influenced by the US, Japan and Korea but described by national labels like “K” (Korea) or “J” (Japan) . Both K-pop and J-pop share strikingly similar idioms: use of English, idols dancing as a group, fans doing fanchants, idols acting demurely for a mass audience, with music indistinguishable from western music.

What we call “K-pop” is mainly idol pop in Korea, but even non K-pop genres are heavily influenced by American genres, such as indies singers using acoustic guitars, K-drama OST singers using Western melodies, or trot singers belting out songs backed by western instruments, using western melodies and notation. This is not surprising since Asian Americans or Asian sojourners who lived in America played a key role in establishing J-pop and K-pop.

BTS at the White House in 2022

The flow of culture also reaches from Asia to America. BTS attained such popularity that they spoke out against Asian hate at the White House in 2022 as part of Asian American-Pacific Islander month. The only problem? None of the BTS members were American. Fans on both sides of the Pacific didn’t seem to mind because the distinction between Asian and Asian American had become melded in K-pop.

Afterward

Condensed version of the BBC report on Kitagawa.

Four Leaves member Kita Kōji went public in 1988 with accusations of sexual abuse by Kitagawa, only to be met by a collective silence from the mainstream Japanese news outlets. TV stations and newspapers were afraid to offend Kitagawa and lose access to his popular idols. Kitagawa died in 2019, and afterwards the BBC revealed his rapes of hundreds of young male trainees, and the coverup of his atrocities by the Japanese media and music industry.

In the Internet Age, news travels fast and across borders and the BBC report could not be ignored. Survivors of his abuse like Okamoto Kauan stepped forward and detailed the violations that Kitagawa inflicted on them. Now associated with the stench of Kitagawa’s depravities, Johnny & Associates in 2023 split into two agencies “Smile up” to provide reparations for Kitagawa’s sexual abuse, and “Starto Entertainment,” to manage their currently existing acts.

Both BTS and Arashi went on hiatus by 2023. BTS members did so for mandatory military service and to focus on solo albums, and Arashi, to pursue individual projects. Fans are eagerly awaiting when all BTS members finish their military service and reunite.

I still listen to K-pop in my car, but now I listen to a lot more J-pop. In the end, what’s the difference?

Discussion Questions

- What is “Pop Pacific”?

- How did the author’s view of K-pop change from 1995 to now?

- The author says that K-pop and J-pop are “transnational” music forms. What does that mean? (HINT: look at how K-pop and J-pop were shaped by places like Korean/Japanese neighborhoods in the U.S., military bases, and migrations.

- What tensions arise from Japanese influence in modern K-pop (e.g. comments about who influenced whom), given the history between Korea and Japan?

- The author notes that today many students want to study Korean history because of K-pop. What are other examples where pop culture encouraged people to learn more about another country or language?

- If K-pop and J-pop are now very similar, does it matter which label we use? Why?

Add new comment