Kealiʻi Reichel’s “Ka Nohona Pili Kai” (“The Living By the Sea,” 2003), a beautiful Hawaiian language song, extols the peacefulness of living in a seaside home. This melodic and soothing song is so wildly popular in Hawaii that you can hear it on the radio, at music festivals, and high school graduations. It is also Reichel’s beautiful interpretation of a song from Okinawa.

Keali'i Reichel. By Charles Haynes, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Okinawan singer Rimi Natsukawa released “Nada Sousou” (“Tears are falling,” 涙そうそう) in 2002, and this lovely melody became her signature hit. She often sings the song to the accompaniment of an Okinawan shamisen. The lyrics are a touching remembrance of a deceased relative.

However, even this was a cover of a song written by the Okinawan band BEGIN, and performed by Japanese (non-Okinawan) singer Moriyama Ryoko in 1998. Moriyama wrote the lyrics to mourn the death of her brother. BEGIN later popularized their own cover of the song in 2000, and the version released by Natsukawa came after that.

Rather than say this is a copy of that, or that is a copy of this, these singers acknowledge that they are creating a common music and invoking each other. Reichel performs in Japan to applause from audiences who recognize it as his interpretation of an Okinawan hit. Natsukawa performed on TV with Konishiki, a Hawaii-born singer of Samoan ancestry (and former sumo ozeki champion) performing both versions of the song. Begin, who wrote this song, often performs in colorful Okinawan kariyushi shirts, which were inspired by the aloha shirts that a Okinawan hotel president noticed on a visit to Hawaii in the 1970s. The song is an example of a shared Pacific culture.

Perhaps this shared culture reflects the similar historical trajectories of Hawai‘i and Okinawa. Both were independent kingdoms conquered by imperial nations. The US helped overthrow the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, paving the way for annexation in 1898 while Japan abolished the royal government of the Ryukyu Kingdom and officially annexed it as Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Both Hawaii and Okinawa were ruled by imperial states that sought to erase ethnic differences - the suppression of Native Hawaiian culture under US rule, and the forced assimilation policies of the Japanese against Okinawan culture. Both experienced WWII battles: the bombing of Pearl Harbor (1941) and the Battle of Okinawa (1945).

Japan’s defeat in WWII led to a new colonial master - the Americans, who administered Okinawa until its reversion to Japan in 1972. Even afterwards, with Japan as home to the largest overseas presence of US military personnel (53,000 troops), US military bases dominated Okinawa. The people of both Hawaii and Okinawa live on heavily militarized islands due to the presence of the bases. About 10% of Hawaii’s population of 1.4 million consists of military and their dependents, while Okinawa also houses a large population of American military and their families (26,000 active duty personnel and 12,000 dependents).

Also, both locales share elements of a common culture and sense of belonging to a common transpacific culture through people (relatives) and family histories. Hawaii is home to a large population of people of Okinawan descent (about 3% of the state). After the devastation of the war, in which at least a quarter of Okinawa’s population perished, Hawai‘i Okinawans purchased 550 pigs to ship to Okinawa to help rebuild Okinawan pig farming. And both locales struggle with military-local relations, as the only other major industry is tourism. Because of the large military presence, SPAM, a food issued to US soldiers during the war, has become a part of the local cuisines in both Hawaii (spam musubi) and Okinawa (goya champuru).

Extend this logic to Korea, and one sees a larger picture of shared cultural influences. The Japanese took over the Korean Empire and ruled it as a colony from 1910 to 1945. Like in Okinawa, the Japanese government pursued a policy of forced assimilation to replace Korean culture with Japanese culture for example by banning Korean language media during the war. After liberation, Korea became part of the US Cold War empire, and today houses 28,500 American troops, third-largest overseas military presence after Japan and Germany. Just as in Okinawa and Hawaii, Spam has become a part of the Korean culinary scene, for example in budae jjigae (army base stew). In Japan, Okinawa, and Korea, American music entered and transformed the local music scene, as musicians made a living performing at US military bases. Japanese jazz legend and movie actress Eri Chiemi first performed at base clubs, learning to sing US standards such as her 1952 cover of Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz”. Korean diva Patti Kim debuted at an American base, leading to a distinguished career. The Tamamoto family siblings, who later made up the Japanese 1970s pop group Finger 5 also gained experience performing for US soldiers.

Often, national or local labels like “Japanese,” “Okinawan,” “Korean,” or even “American” actually indicate items of transnational origin. What we call Korean or Japanese popular music can only be understood in the larger context of the relations between Japan, Korea and the United States. In the postwar, both Korea and Japan were bound tightly to the United States as their main ally and cultural inspiration. While American influence helped create a hybridized culture in East Asia, Japanese and Koreans did not just accept American or Western music, but rather chose to listen to American style music created by Japanese and Korean performers. For example, in the 1960s, the rock band craze from the UK swept the US, and from there spread to Japan and Korea. This became known as “Group Sounds” in these nations, with Japanese bands like the Spiders and Korean bands like Add4.

Since this blog post began with Hawaii, it should end with Hawaii. Hawaii is also one of the centers of the pop pacific. Portuguese immigrants brought guitars to the islands in the mid-19th century. The steel guitar (kika kila in Hawaiian), invented in 1889 by Native Hawaiian teenager Joseph Kekuku, influenced not just Hawaiian music, but also genres such as country music, rock and roll and the blues. As a Smithsonian article notes, after the illegal US-sponsored overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom in 1893, followed by the annexation of Hawaii to the US in 1898, Hawaiians such as Kekuku left the islands and traveled the US as performers. There, Hawaiian performers introduced the steel guitar to other musicians, who then adopted this instrument to country music and the blues. Michael Wright in Acoustic Guitar Magazine asserts that Hawaiian music fueled America’s interest in playing guitars. The pedal steel guitar even spread to Nigeria where it became part of the juju music scene in the late 1970s.

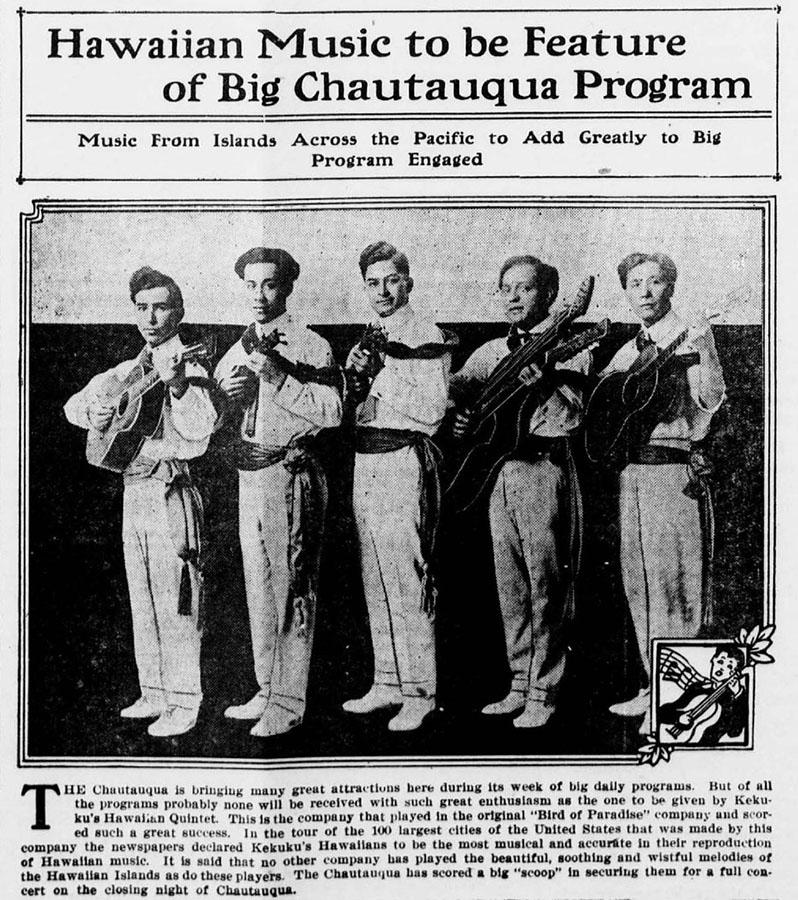

A picture of the Kekuku's Hawaiian Quintet in a 1916 newspaper.

Today, the Pop Pacific blending of the Pacific, America, and Asia continues in Hawai‘i. The steel guitar has largely fallen out of favor with young people in the islands, and Hawaiian music is now mostly slack key guitar (A guitar re-tuned by native Hawaiians and played plucked) or Jahwaiian music (a blend of reggae and Hawaiian sounds). American, Japanese and Korean tourists flock to Hawaii, and there are Japanese and Korean language broadcast stations. Hawaii artists like Ito Yuna, Angela Aki or Def Tech have also been popular in J-pop in the early 2000s. As you can see, Reichel’s and Natsukawa’s interpretations of “Nada sousou” show the shared historical and cultural connections of the Pop Pacific.

Discussion Questions

- What similarities do Hawai‘i and Okinawa share in their histories of colonization and militarization?

- How does the story of “Nada Sousou” illustrate the idea of a shared Pacific culture rather than a simple case of cultural copying?

- Both Hawai‘i and Okinawa have U.S. military bases that shaped local economies, food (like Spam), and music. How do military presences create cultural exchange, and what tensions do they also create?

- The article notes how American influence in Japan, Okinawa, and Korea produced hybridized music rather than one-way cultural domination. Do you think “hybrid culture” is a fairer way to describe globalization than “Americanization”? Why or why not?

- The steel guitar, invented in Hawai‘i, went on to influence country, blues, and even Nigerian juju music. Can you think of another example where a local invention or tradition reshaped global culture?

- The author describes Hawai‘i as a “center of the Pop Pacific.” How does this idea change the way we think about Hawai‘i—not just as a tourist destination, but as a cultural crossroads?

Add new comment