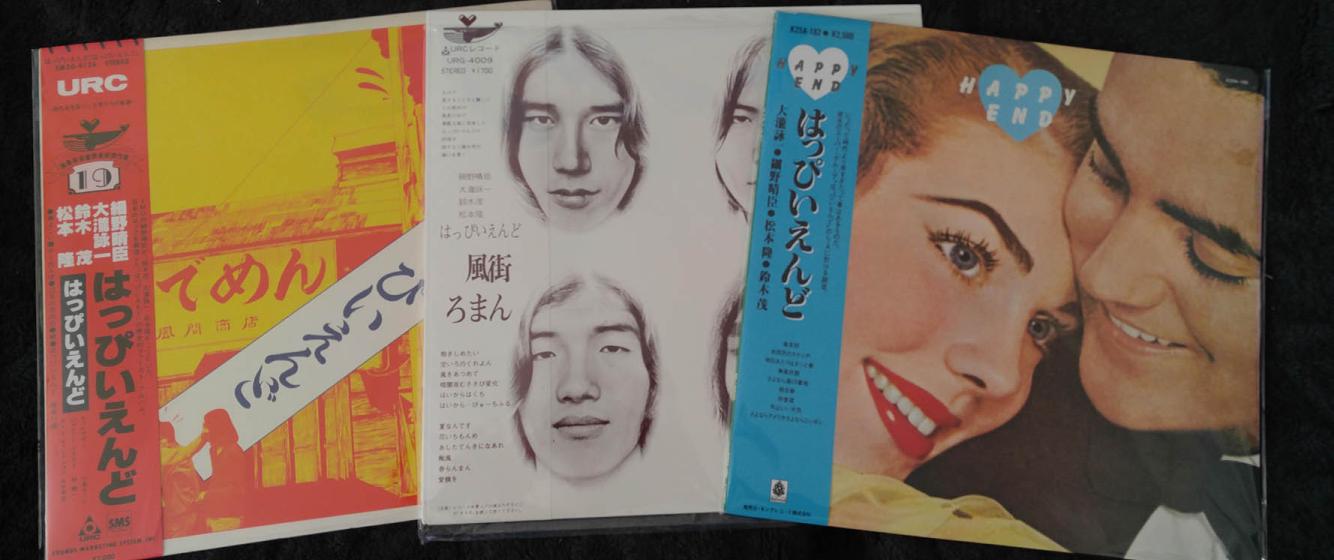

Happy End’s Happy End: The Band that Made “Japanese” Rock

In 1971, Japanese Folk Music juggernaut Okabayashi Nobuyasu, Like America’s Bob Dylan, shocked his fans at the (in)famous 1971 Tokyo concert by electrifying his music. He played an electric guitar on stage for the first time, and was backed by a group of college students who were also playing electrically amplified instruments. This band, which came to be known as Happy End, had at least as much of an impact on Japanese pop music as did Okabayashi, though they took it in a different direction.

Happy End made Rock and Roll possible in Japanese. Not J-Rock, which is a marketing category invented in the 21st century. This was Rock, and the fact that Happy End sang it in Japanese was perhaps one of the key things that made it part of the global Rock movement. To get there, the members of Happy End had to pay their dues touring small theaters and bars in out-of-the-way towns, skipping classes, and meals, changing clothes in gas station restrooms, and spending nights, when they could, at each others’ parents homes to save on hotel costs.

Touring around the country to build a fan base and a record deal is a story that is as old as popular music itself. It often begins, as it did for Happy End, with a group of college kids bitten by the music bug. Happy End had been Okabayashi Nobuyasu’s electric debut backup band. By 1972 they were becoming a phenomenon themselves.

Happy End never intended to play folk music like Okabayashi. None of them even owned an acoustic guitar. They were all inspired by the college rock scene of the late 1960s, not its folk antecedent. Their model was the American rock band Buffalo Springfield. From the beginning, they aspired to be something new.

Inoue Yosui's 1972 song "Kasa ga nai" (I Have No Umbrella) exemplifies the shift in early 1970s Japanese music from protest songs to personal expression.

They sang songs that were critical of the problems of the world, sure. But in those songs they were more interested in individual feelings than in solving the social issues. Happy End was not unique here. This was the trend in the early 1970s. The music became more personal, more emotional, and less about protest. Inoue Yosui’s song “Kasa ga nai” (I have no umbrella) is a classic example. Described by Michael Bourdaughs in his book Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Japan, the song mentions the problems of the world, but the singer is clearly more concerned about his own problem. He wants to go visit his girlfriend, but it is raining and he has no umbrella. The song is all about a personal experience, though it occurs in the context of major social and political problems.

This is “New Music” - Japan’s 1970s pop for a new world in which the shape of the social order is already decided.” For Okabayashi before 1971, the social order was malleable, full of potential, and humans had free will. His 1971 song “The Long Road to Freedom” (Jiyu e no nagai michi) makes it clear that he sees it as, if difficult, also possible to find freedom. That changed in the span of only a few years. For Inoue Yosui after 1972, the social and political institutions that support capitalism were the only reality. No new future was possible. The only thing a young person could do was worry about their inner emotional life. In a very real way, people had no umbrella to protect them from capitalist reality. They had no way to change the status quo. So Happy End sang about living within the status quo. Rather than protest music, this was inner life music. Perhaps Happy End’s most well-known and prolific member, Hosono Haruomi, got his start here singing songs about living within a carefully structured society in which inner life was the only way to escape a political reality that felt set in concrete.

Happy End: Natsu nan desu (no English available)

Happy End's biggest claim to fame today is that they were the first Japanese rock band to sing in Japanese. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the biggest philosophical argument among Japanese rockers was whether rock had to be sung in English. Some thought it was possible to sing it in Japanese. The problem was that Japanese is not a language with lots of stress in the pronunciation of words. The rhythm of English is very clear stress on the first syllable of mose words. This makes it relatively easy to sing English words within a 4/4 time signature song. Japanese, on the other hand, has a different rhythm and a different style of emphasis. To sing rock in the rhythmic way that it works in English requires one to sing in a way that actually sounds kind of foreign. Singing with an accent. The question was whether this would make any sense to listeners. Happy End came down on the side of Japanese. They did so, according to them, because it never occurred to them not to sing in their native language. They just felt more expressive that way. This despite their habit of listening to American rock. This seems obvious now, in hindsight, if we recognize that their focus was on an inner life. Japanese was the key to their own inner life, and thus necessary for their music. They were inspired by Buffalo Springfield, but they were not looking to sound like Buffalo Springfield.

In that sense, then, Happy End is the birth of a truly Japanese rock sound. This does not place them at the head of the history of "J-rock," whatever the definition of that may be (see my earlier post "Jpop is JWAVE pop”). Instead, it makes them a critical part of global Rock history. Just Rock, unqualified by a national modifier. They were a development within the history of Rock more broadly. Theirs is a part of the story of Rock's diffusion worldwide in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Happy End (Band).” In Wikipedia, March 29, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Happy_End_(band)&oldid=1216120773.

“Nobuyasu Okabayashi - 自由への長い旅 (Jiyū e No Nagai Tabi) (English Translation).” Accessed May 27, 2024. https://lyricstranslate.com/en/jiy%C5%AB-e-no-nagai-tabi-long-journey-freedom.html.

Bourdaghs, Michael K. Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop. Asia Perspectives: History, Society, and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Seraki, Dimitri. “New Rock and Happy End - Origins of Japanese Rock.” Fullfrontal.Moe (blog), December 2, 2021. https://fullfrontal.moe/new-rock-and-happy-end-origins-of-japanese-rock/.

Tobe, Name Nobuyasu Okabayashi Role Singer Albums Mirumaeni, Watashi Wo Danzai Seyo, Kuruizaki, うつし絵, ラブソングス, セレナーデ, Oira Ichi Nuketa, et al. “Nobuyasu Okabayashi - Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia.” Alchetron.com, August 18, 2017. https://alchetron.com/Nobuyasu-Okabayashi.

Add new comment