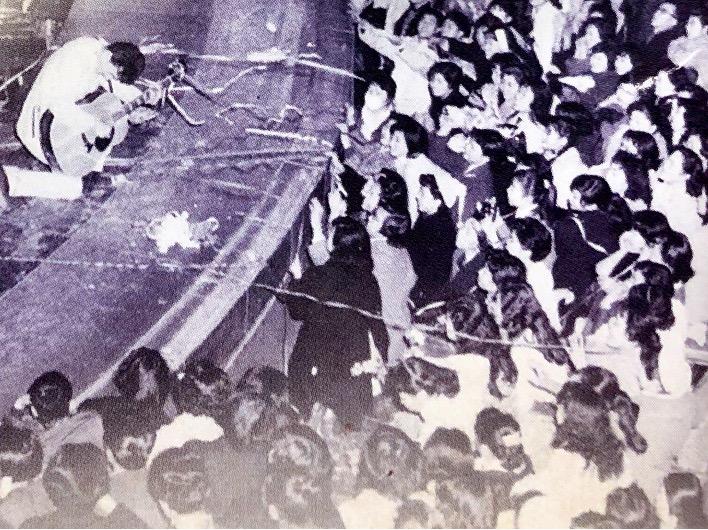

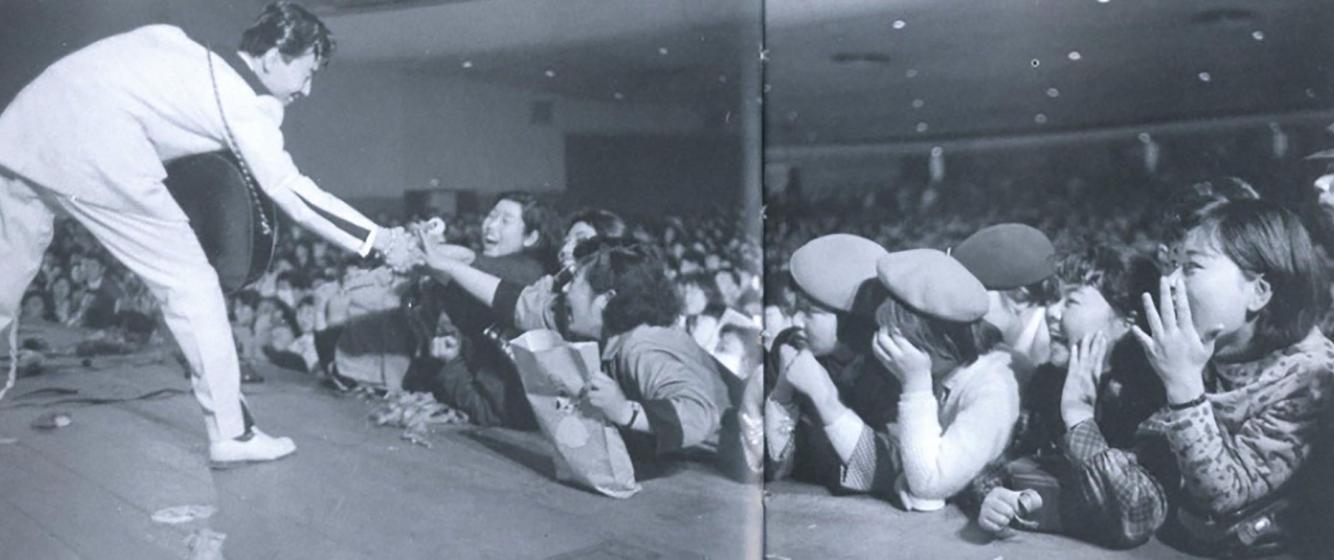

The Nichigeki Western Carnival of 1958, in which Japanese rokabirī (rockabilly) performers played to thousands of mostly frenzied young girls in Japan’s largest music venue, set Japan abuzz. While the musicians writhed on stage as they performed, young women threw paper streamers or panties at them and even dragged them off stage. Further rockabilly performances at the Shinjuku and Osaka in April, caused more pandemonium, setting off a moral panic fueled by the emerging medium of television and fears over the behavior of Japanese youth.

TV, which began broadcasting in Japan in 1953, popularized rokabirī. Some young girls, who had watched rokabirī performances on television at home or at coffee shops, caught rokabirī fever, skipped school, and ended up joining the ranks of the young girls at concerts. If Elvis, with his hip-shaking on stage, seemed scandalous in America, then imagine the uproar it caused in Japan, where it was common for singers to stay still while singing. The unconventional actions of the singers seemed to come from the realm of the grotesque. The Shûkan Asahi described one singer’s gestures: “[He] points both legs inward, lowers his back, and bends his legs at a 35-degree angle. And then he thrusts the guitar in the direction of tomorrow, and waddles like a child with polio.”[1]

Rockabilly guitarist writhing on stage at the Nichigeki Western Carnival

Social critic Katō Hidetoshi theorized that the postures of singers symbolized the awkward social positions of Japanese teens:

To the teens, doesn’t the oppressed posture in rockabilly symbolize the sense of oppression they receive from adults? They can forcefully straighten their backs if they want to and can move like grown adults. However, whenever they straighten their backs up, adults firmly push them back down. This is the meaning of the rockabilly posture. They lower their backs a great deal to escape being pushed down by adults. They are attempting to resist. However, when they are in this low posture, the energy that one normally vents by stretching out has nowhere to go. Their energy is released through waddling like a child with cerebral palsy. Because they cannot naturally release their voices, they end up doing strange screams.[2]

Little did Katō know that the singers improvised these poses based on American album covers since it was hard to get film of rockabilly performances. But his words reflected the unease that Japanese felt over the direction of the youth and rokabirī.

Season of the Sun (1955) and the fears of youth gone crazy

What caused the moral panic? By the early 1950s the prewar values of obedience clashed with newer American-influenced values of individualism. Adults believed that youth, confused by American reforms, were channeling their dissatisfaction into violence causing a surge in juvenile delinquency. In 1954, there were four times more juvenile arrests than in any of the prewar years. In Osaka, graduates beat up a teacher and trashed their school after commencement ceremonies.[3] Also, university students seemed to be caught up in the crime wave. In 1956, of the 5,664 students arrested for major crimes, about one in five were from universities.[4]

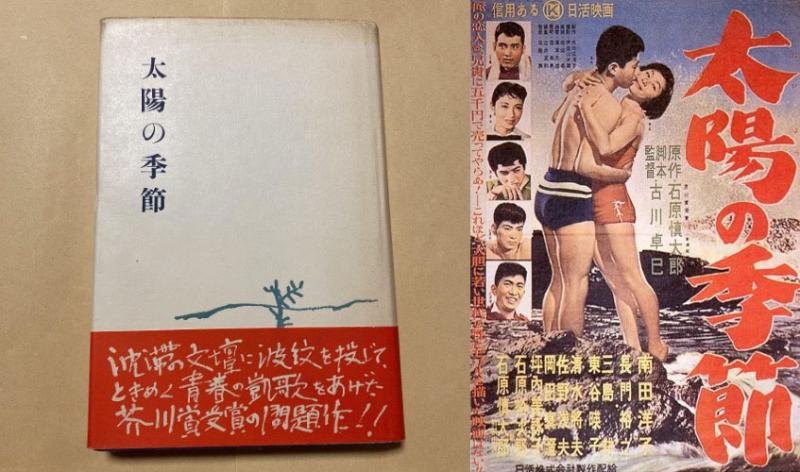

Ishihara Shintarō’s 1955 novel, Season of the Sun (Taiyō no Kisetsu), which dealt with the lives of well-to-do but amoral and violent high school students, fueled the concerns over youth. This novel both criticized and sensationalized the youth who could only express themselves through mindless pleasure and violence, such as brawling and sex. This novel won Ishihara the Akutagawa prize in Japanese literature and drew attention to the problems of youth. [5]

Fans throwing paper streamers onto the stage at the Western Carnival (1958)

Movies took their cue from this novel, glorifying the values that Ishihara intended to critique. Nikkatsu studios turned the work itself into a 1956 hit film starring Ishihara’s brother. The scenes of the main protagonists, a high school boxing team who spent their days drinking, brawling, and chasing girls, shocked and titillated the nation. Taiyō no Kisetsu spawned a whole genre of teen delinquency films known as Taiyōzoku-eiga (Sun-tribe movies) and fanned the debates surrounding postwar youth delinquency. The critique of rockabilly duckwalking on stage at the Nichigeki Western Carnival fit perfectly into the national debate over youth gone wild caused by the Sun tribe films.

The fear of “Violence Classroom” (1955)

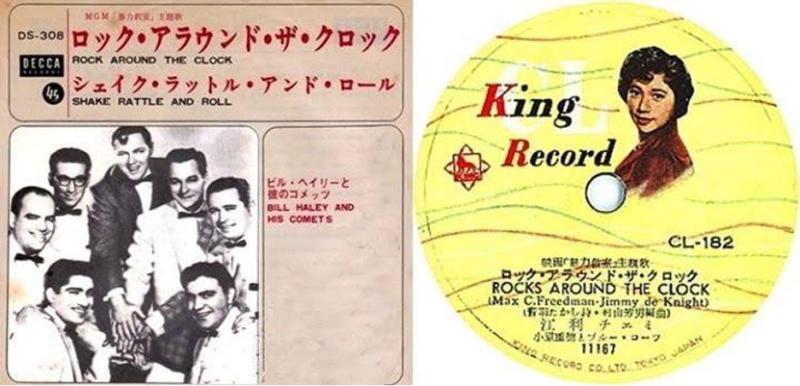

The movie Blackboard Jungle (1955), which set off a controversy in the U.S, was released in Japan during the debate over Ishihara’s novel. The movie was about juvenile delinquents in a New York high school. The theme song, Bill Haley and the Comet’s rockabilly cover of “Rock around the clock”(1955), played in the opening scenes to set the tone of delinquent youth. The playful song thus became an anthem for youthful rebellion.[6]

Retitled the more provocative Violence classroom (Bōryoku kyōshitsu暴力教室) in Japanese, the Ministry of Education designated the a movie with a warning (要注意作品). This movie, like in America, gave rockabilly an association with teen delinquency. Japanese teens in the rokabirī zoku (rockabilly tribe) adopted rockabilly fashion such as leather jackets or pompadours, horrifying parents. To capitalize on the movie’s notoriety without offending parents, Chiemi Eri even sang a jazzier non-rockabilly cover of "Rock Around the Clock" (1955) with different Japanese lyrics and scat singing, thus removing some of its rebellious connotations.[7]

Bill Haley and the Comet’s cover of “Rock around the Clock” alongside Eri Chiemi’s jazzier non-rockabilly cover.

The public attack on rokabirī , which gained national prominence through the Nichigeki Western Carnival just a year after the movie Taiyō no Kisetsu, was part of a larger effort to regulate postwar youth. Reformers called for stricter parental control and planned to reintroduce prewar morals courses into the curriculum. [8] In 1958, after TBS television broadcast a rokabirī concert that attracted much criticism, the station stopped broadcasting rockabilly performances for two years. Facing much pressure, rockabilly died out.

TV as the wave of the future

But TV showed Watanabe Misa from the Nabepro entertainment agency that managed the Nichigeki Western Carnival, a new business model. By 1960, half of homes throughout the nation had a television, creating a critical mass of audiences able to watch nationwide programming. Impressed at the reaction to the daytime TV rockabilly broadcast, Watanabe and her husband developed an entertainment model to take advantage of this new medium. The singers at the carnival became NabePro entertainers with a softer sound and appeared on TV as family-friendly entertainers.[9]

Ishihara Shintaro’s “Taiyo no kisetsu” (season of the sun) and its movie adaptation in 1956 reflected and fed the moral panic over youth gone crazy.

Rokabirī, feared by the press and parents, lay the foundations for the Japanese pops of the 1960s. The Watanabes would lead NabePro to dominance in Japan. Hori Takeo, the organizer of the event, would part ways with the Watanabes and establish his own agency "Horipro". The rockabilly concert series laid the foundation for two of Japan’s major entertainment agencies in a new business paradigm combining television and music. Tobita says, “…that the equating of the “entertainment world” with the “entertainment business” in modern Japan started with the Nichigeki Western Carnival.”[10]

In 2004, the “Rockabilly Three Guys” of Masaaki Hirao, Mickey Curtis, and Keijirō Yamashita announced they would hold a concert in Tokyo, the first time the three of them performed together since the 1958 Western Carnival. Hirao said, "If the carnival is a class reunion, the next concert will be a battle. Kei-chan is country rock, Mickey is jazz rock, and I am rock and roll.”[11] The rockabilly performers split off into different directions, reflecting how this concert influenced Japanese pops, marking the beginning of Japanese pops aimed at teens (which will be the subject of a future post).

Personal note

In the late 1990s I was ready to write about rokabirī and the Taiyōzoku for my dissertation. Then I bumped into another graduate student who knew much more than me about this topic. With my confidence deflated, I decided to write about something else. What a joy to revisit this topic a quarter century later! Much thanks to Professor Michael Furmanovsky, who shared with me his treasure trove of sources.

Part of this article uses material previously published in my book “A Nation of a Hundred Million Idiots”?: A Social History of Japanese Television 1953 – 1973.

[1] Shûkan Asahi , 17 March 1953 quoted in Hidetoshi Katō, Rokabirī No Imi Suru Mono (the Meaning of Rockabilly) [Hōsō Asahi (April 1958), Internet] (April 1958, accessed 14 July 2003); available from http://katodb.la.coocan.jp/doc/text/2369.html

[2] Kato, “the meaning of rockabilly,” 1958.

[3] "Black Cloud in Japan," Time, 9 April 1956, 102-104.

[4] "Learned Criminals," Time, 8 July 1957, 34.

[5] "The Rising Sun Tribe," Time, 17 December 1956, 37.

[6] David Deacon-Joyner, “‘(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock’—Bill Haley and His Comets (1954),” Library of Congress, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-boa….

[7] NAKAMURA Toshio, “When Was the Music Called ‘Rock Day’ Rock Born? ..."Rock Around the Clock" (「ロックの日」ロックと呼ばれる音楽が誕生したのはいつなのだろうか?...「ロック・アラウンド・ザ・クロック」),” Adult’s Music Calendar (Otona no Music Calendar) , June 9, 2015, http://music-calendar.jp/2015060901.

[8] "Black Cloud in Japan," 104.

[9] Michael Furmanovsky, “Rokabirī,” Student Radicalism and the Japanization of American Pop Culture, 1955-60” Intercultural Studies, 12 45-56, March 2008.

[10] TOBETA Makoto, “What is the legendary event "Nichigeki Western Carnival" that changed the entertainment world? "Birth of the entertainment world" trial reading” (“芸能界を大きく作り変えた伝説のイベント「日劇ウエスタン・カーニバル」とは?『芸能界誕生』試し読み: 試し読み,” Book Bang, December 23, 2022, https://www.bookbang.jp/article/742535.

[11] “‘Rockabilly Sannin Otoko’ first stage concert in Hibiya, Tokyo,” (`Rokabirī san'nin'otoko' no hatsu sutēji Tōkyō Hibiya de kyōen konsāto 「ロカビリー三人男」の初ステージ 東京・日比谷で共演コンサート), Asahi Shimbun, February 28, 2004. P 13.

Discussion Questions

- What was the Nichigeki Western Carnival and what unusual things happened there in 1958?

- How did TV help rockabilly music become popular in Japan?

- How was rockabilly connected to fears about young people, movies, and changing morals?

- Can you think of a recent example in your country where a new music or media trend caused concern or moral panic among older generations?

- How might modern social media play a similar role to television in spreading youth culture and causing public concern?

- How does understanding this “Rokabirī panic” change how you view the role of youth culture in history, especially in terms of expressing identity or resisting norms?

Add new comment