“The Girl is Mine”: Selling Dreams in Akihabara

A former President of Polygram Group Distribution once noted that “Music isn’t black or white, it’s green.” He’s totally right about this. We like our popular songs to grab our emotions and sound cool. But fans, artists, and academics alike easily forget that popular music is a business.

The goal of management and record companies isn’t to distribute art. They want to turn art into money. Often, they’re pretty successful at doing this. In 2022 total global music sales were USD 26.2 billion. That’s larger than the total economies of Trinidad and Tobago, Georgia, and Bosnia/Herzegovina. Japan's share, $2.4 billion, made it second only to the United States. But Japan’s market is unique. More than 66% is in the form of CD and record sales. This causes a distortion in the music industry in Japan. Record manufacturers, artists, and artist management companies find it more profitable to sell physical music to their customers rather than deal with the low-profit margins associated with music streaming and downloads.

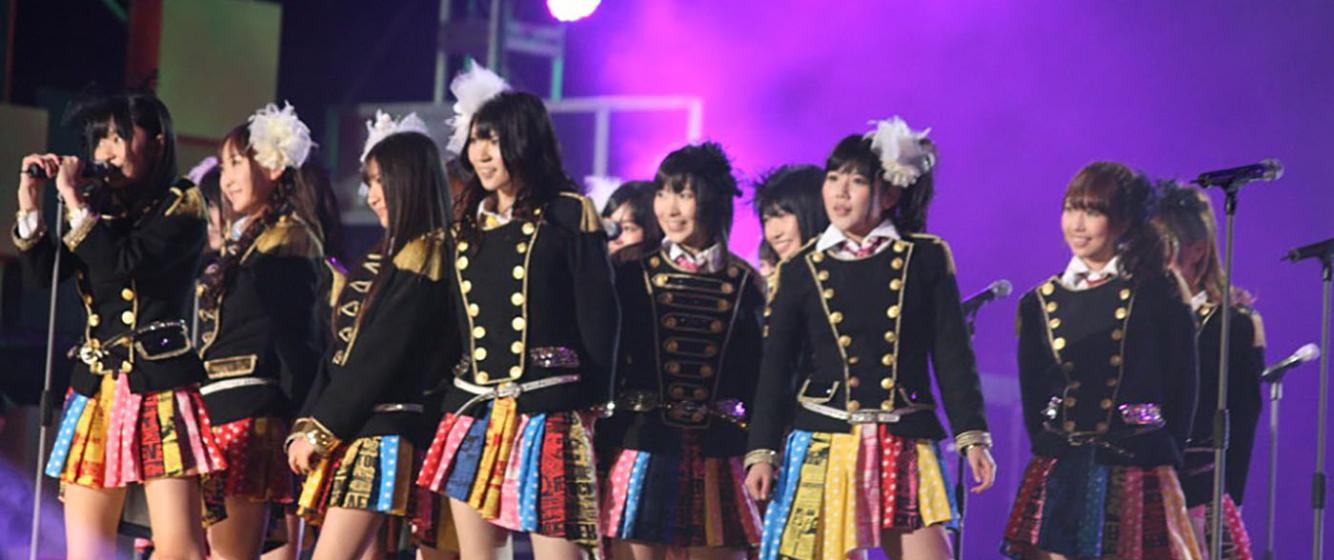

One great example of how Japanese management companies have learned to meet the market where it is involves a girl idol group known as AKB48. Based in Akihabara (the nickname for which is Akiba, or AKB), this all-girl group produced by Akimoto Yasushi has taken idol marketing to new levels. The marketing works because of the Japanese market preference for buying music on physical media like CDs. In their prime, around 2011-2014 (and as recently as 2020), AKB almost continuously topped the year-end music charts. This was because they had such a high volume of CD sales. In fact, though, most Japanese are not AKB48 fans. What made it possible for AKB48 to dominate music sales while not actually being the most popular act in Japan? Here’s how it worked.

The girls are chosen because they look and behave like everyone else in Japan. They are all good-looking, but mostly in a ‘girl next door’ way. Most also have no professional training in dancing or singing. This is part of their appeal. They start out as amateurs. Once in the group, they are given minimal training and then set to perform live almost daily in their base theater in the Don Quijote department store in Akihabara. Fans get direct experience of the group in a small theater where performances are almost personal and often interactive. They can see the new members of the group this way, and choose girls they want to support.

Now, many of my friends have a hard time believing this, but in fact, the foundation of fan activity is about supporting your favorite girl as she learns and grows in the business, going from amateur girl next door to professional performer. Fans buy CDs because within each CD package is a ticket that allows the fan to enter a code online and vote each June for a favorite member of the band. There are also tickets in the CD cases for meet-and-greet events. So fans get to meet their favorite AKB48 members, and they get to vote for their favorite girl, supporting her rise to stardom. The results of the vote are broadcast on TV each June. In that show, the number one through number 48 girls are named and introduced. Each is interviewed. Each thanks their fans for voting for them. The girl who gets the most votes becomes number one and gets to stand front and center in the awards show and in music videos and concerts for the year. She also gets the most solos and most commercial airtime. This is a reward for her fans as much as for her.

It is seriously important that the votes for girls lower than number 48 still count. Each girl is given training in singing and dancing based on her popularity. If you buy more CDs and vote more times for your favorite girl, she moves up the ranks, gets more training and gets seen by more fans, leading to increasing popularity and more votes. Fans see themselves as actual participants in the success of their favorites. In a way, one is a fan as much a part of her success as other people in her life - her parents, her friends, all of the professionals who encouraged her along the way, and the people who voted for her. This is why most fans buy multiple copies of an AKB48 CD. Some take this very seriously indeed. In 2014, a single fan spent $300,000 on AKB 48 CDs in order to promote his favorite member of the group.[6] In fact, AKB48 has two key market demographics. One is girls and young women between about 11 and 18 years old. The biggest, though, that generates the most sales, is men over 30. They have the deepest pockets, and so can afford the most CDs.

Georges Seguin (Okki), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Rino Sashihara of AKB48 during lecture at Japan Expo 2009 (Paris, France).

Like many of my American friends, you are going to say, “okay, so this is really about men’s sexual desire for younger women.” Well, you would not be totally wrong. On the other hand, things are more complicated than that. One of their first music videos (and you must know by now that AKB48 sells through visual appeal, not through the appeal of their music), is for a song called “Heavy Rotation.” The song starts with the words, “I want you! I need you! I love you!” The rest of the words are sticky sweet images that suggest an early teen crush. But they are also ambivalent enough to refer to something more suggestive, sexual, and grown-up. They hint at sexuality which is also suggested by the costumes and some of the elements of the music video. It begins, for example, with one of the girls realizing someone has been watching through the keyhole as she removes her dress to reveal sexy pink underclothes. Her face looks surprised and excited. Half the video is gratuitous shots of the girls in sheer nightclothes having a pillow fight and rolling around on a cushion-covered floor. There are no men in the video, nor any implications of any men interacting with the girls. It is a voyeuristic fantasy, playing out what men might imagine they could see if they watched a sleepover with 48 cutesy girls in lingerie. So yes, there is an erotic element here. But in public, and in most dance performances, AKB48 members dress demurely, are encouraged to look cute and cuddly, rather than sexy, and are required by their contracts to avoid having a boyfriend or even dating. In these cases, the emphasis is on purity, not sexuality. In the videos, fans don’t touch, and there are no romantic encounters. It is all vicarious.

Karl Baron from Malmö, Sweden, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

AKB48 Store in Singapore. AKB48 is a multinational franchise operation.

Even though it cannot be enforced because of labor laws in Japan, group members are not supposed to have boyfriends or dates. This leaves room for fans to imagine them as pure and innocent, and also as available. AKB48’s success exists on the line between purity and puberty, innocence and adult desire. To see this video, and AKB48, as only about adult desire ignores the fact that they are marketed to all of Japan, and are idols for pre-teen girls as well. Their wholesome image exists alongside voyeuristic eroticism. AKB48 are neither women nor girls. They are girls becoming women. This is the key to their market success. Both are used to sell CDs, preferably multiple copies to every buyer. In this way, Akimoto has been able to maximize physical sales and his own profits. By creating specific CD lines (A line, K line, and B line, each of which features a different girl on the cover, though the same song list), franchising the idea so that there are numerous branch groups - NMB48 in Namba, Osaka, HKT48 in Hakata, even JKT48 in Jakarta - encouraging fans to support their favorite members, and making it possible to vote for and meet the girls only by buying CDs, he has created a marketing juggernaut in which AKB48 outsells their musical weight through activation of fans. AKB48 is not really selling music. They are selling idols and dreams - the dream of being an idol, the dream of meeting an idol, and finally the dream of helping someone you care about reach their dream. These are potent products.

Though AKB48 now seems to be in decline, some of its franchise groups: Nogizaka46, Sakurazaka46, and Hinatazaka46 are at their peak in sales. They function according to a new hybrid business model. There is no more fan voting. The girls dress more conservatively - much like a French private all-girls high school and project an image of elegance and social grace. Perhaps in later posts, it will be worth exploring some of the controversies and market changes that have led to this new face of Akimoto’s pop music empire, including the influence of Takarazuka and Kpop’s ability to maximize sales by focusing on a primarily female audience. The key takeaway, though, is that AKB48 may be entertaining, but the group is designed on a specific, and revolutionary business model that fits the desires of specific Japanese consumers, and the economics of the Japanese market.

References

Baseel, Casey. "Akb48 Fan Shows His Love the Only Way He Knows How: By Buying $300,000 Worth of Cds." In Rocket News: Rocket News, 2014.

Endo, Takahiro. "An Institutional Analysis of the Resale Price Maintenance System for Publications in Japan: The Two-Tier Tug-of-War and the Survival of the System." edited by Hitotsubashi University Graduate School of Commerce and Management, 20. Tokyo: Hitotsubashi University Repository, 2006.

"I.F.P.I. Global Music Report 2016." IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, http://www.ifpi.org/news/IFPI-GLOBAL-MUSIC-REPORT-2016.

Japan, Recording Industry Association of. "Riaj Yearbook 2015: Statistics Trends: The Recording Industry in Japan 2015." Recording Industry Association of Japan, http://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2015E.pdf

2015 ORICON rankings: http://aramajapan.com/news/music/oricon-unveils-their-yearly-sales-rankings-for-2015/53356/

Weinstein, Deena. Heavy Metal : The Music and Its Culture. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press,, 2009.

Yang, Jeff. "Asian Pop Hello Kitty! Rock! Rock!" In SFGATE. San Francisco: San Francisco Chronicle, 2005.

Comments

Cultural Contexts in Understanding Japanese Idol Culture.

This article offers an interesting perspective, but it seems to approach Japanese idol culture primarily through an external and critical lens, rather than engaging with how it is understood within Japan itself.

Many of the social and emotional dynamics described here—particularly ideas of admiration, care, and community—carry different cultural meanings in Japan, where idol culture often centers on empathy, sincerity, and shared growth rather than exploitation.

By focusing mainly on power imbalance or commodification, the article risks reinforcing familiar Western narratives that overlook how Japanese audiences and performers themselves interpret these relationships—as mutual, evolving, and sometimes even healing forms of expression.

Japanese Aesthetics and the Reconsideration of Idol Expression

Following up on my earlier comment, I’d like to share a related perspective that approaches idol culture through the lens of Japanese aesthetics rather than external critique.

There is also a range of Japanese scholarly literature that might offer further context-rich perspectives from within Japan itself. For instance, philosopher Shin’ichi Anzai’s ももクロの美学 (“The Aesthetics of Momoiro Clover Z”) interprets idol culture as an aesthetic and intellectual phenomenon—one that invites empathy and reflection—rather than primarily through frameworks of consumption or power.

Japanese Aesthetics and the Reconsideration of Idol Expression

Writing can be an exercise in finding balance. Your point is well-taken, particularly because of the fact that I was not writing using Aesthetics as a theoretical organizing principle. I do agree that it is important to look at idol culture from within the cultural context of Japan, and to that end, when titling the article, I certainly intended the theme of dreams to include the dreams of the idols themselves, and those who support them. You're right, in the West, particularly in the United States, interpretations of idol culture in Japan orbit around power and gender relations issues. However, in Japan, as you note, supporting idols (oshikatsu) can be both a personal theraputic act, and an instance of socially supporting and caring for someone in a platonic way. I think that can be found in the power/audience kind of analysis in this article as well. The fault here is probably that I was rather too subtle about that. 1200 words is a short form to include detailed theoretical discussion. It is easy to leave things out. Discussions like this help to clarify.

Japanese Aesthetics and the Reconsideration of Idol Expression

Thank you very much for your kind and thoughtful reply. I deeply appreciate the openness with which you’ve engaged this discussion.

Your reflection on “dreams” resonated strongly with me. In Japan, the notion of yume (夢) often carries not just the sense of aspiration, but of a shared emotional horizon—a space where the hopes of performer and supporter intertwine. When idol culture is viewed through that sensibility, what appears from the outside as a power relation often unfolds, from within, as an ethic of mutual care (tasukeai) and sincerity (makoto).

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of idol culture lies precisely in this borderland between art and affection—where aesthetic beauty and emotional virtue overlap. Like earlier popular arts such as ukiyo-e, idols make visible the quiet ethics of everyday life: perseverance, gratitude, and the joy of creating meaning together.

I think your essay already gestures toward this in its theme of “dreams.” I hope that future discussions—yours and others—will continue to explore these layers of feeling and cultural logic that make idol culture not only socially revealing but artistically and philosophically profound.

Thank you again for encouraging such a thoughtful and balanced exchange.

Add new comment