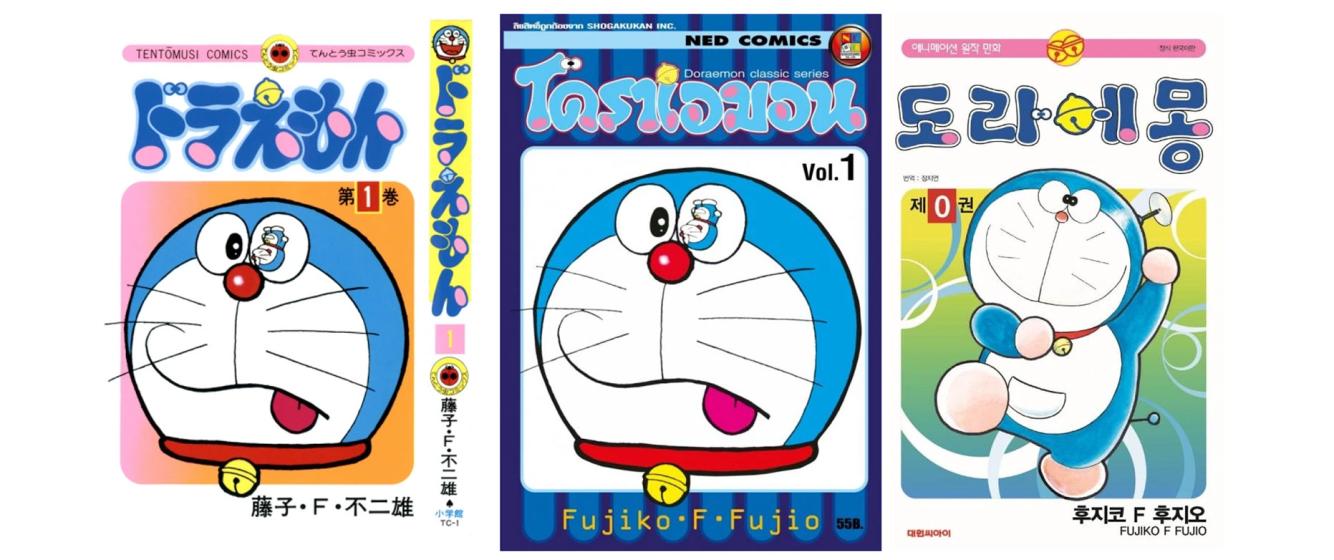

Doraemon in Japanese, Thai, and Korean showing its international popularity in developmental economy nations where kids have to study.

Doraemon as a High Speed Growth Manga (1): Nobi Family as 1960s developmental state family

In 2008, Japan’s foreign ministry named a blue robot cat from the 22nd century a cultural ambassador for Japan. Doraemon is the most famous robot cat in the world, having sold almost 300 million manga copies and being among the best-selling manga ever.

First appearing in a manga in 1969 by Fujiko F Fujio, this robot cat from the future, sent back in time to help his inventor’s great-grandfather overcome his laziness and pass school, has adventures that follow a predictable pattern. NOBI Nobita, an elementary school kid, usually has a problem with school or friends. Doraemon then presents him with an invention from the future that can help, such as a “memory bread” that when pressed upon a book page and eaten, can help one to memorize mass quantities of material to pass a test. And then, seeking a shortcut, Nobita misuses the invention, which causes mayhem, and usually he is worse off in the end.

Doraemon is popular in Indonesia as seen in this video from the Indonesian official site.

The manga has led to a highly successful anime series, first in 1972 and later in 1975. It has spawned countless merchandise and over 44 movies. Overseas, it has been quite popular, being broadcast in over 60 countries. This series is known as Doraemong in South Korea, and dō lā A mèng (哆啦A梦) in China. Hindi dubbed broadcasts of Doraemon were so popular in Bangladesh, where Bengali is the main language, that the government banned these broadcasts.

The English language version of Doraemon has been unable to replicate the success seen in SE and East Asia

Yet, Doraemon was unable to gain traction in the United States. An English adaptation in 2014 never became popular, even when broadcast on one of the Disney cartoon channels. For some reason, Doraemon is wildly popular in East and Southeast Asia, but not in the developed West, except for lower-middle income European nations such as Spain (or so I saw on a Japanese documentary).

A clue lies when we look at the time of Doraemon's manga debut in the late 1960s and anime in the 1970s when the Japanese development state was in full swing. Nobita’s family is lower middle class – having some semblance of respectability but putting pressure on him to move up in life through the exam system. In other words, The Nobi family is representative of the white-collar lower middle class in high-speed growth 1960s Japan, attempting to move up in respectability and affluence. This is not a world that children in the materially wealthy US or Europe can sympathize with. But this is a world that is familiar to children from East Asian developmental states, like Korea, China, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, India, or Indonesia. Nobita’s dreams and pressures are those that children in these societies who aspire to social mobility can relate.

Doraemon as a 1960s developmental state family

Nobita’s family is stuck in the 1960s and represents the values of the up and coming urban lower middle class of 1960s Japan. They live in a modest two-story house in the suburbs. Even in recent portrayals of the 2020s, Nobita’s house seems frozen in the 1960s, devoid of televisions, computers, or a family car. Nobita belongs to a nuclear family consisting of a salaryman father, a housewife mother, and him, which had become the urban ideal in 1960s Japan. Contrast this to the multigenerational extended family of another Japanese manga and anime, Sazae-san, which started in the 1940s. Sazae-san, which became an anime in 1969, is wildly popular in Japan, but relatively unknown outside of it, and represents the 1940s extended family ideal of grandparents, parents and a large number of siblings in Japan.

Further evidence shows that this is a family stuck in the 1960s. The father Nobisuke is a low-level salaryman, who often comes home drunk, having to kowtow to his bosses wishes, and stay out late with his coworkers for drinks. The mother, Tamako, is a housewife charged with making sure Nobita does well in school. Thus, she is always nagging Nobita to study more and she erupts in anger when she sees his poor grades from school.

In the 1960s, Japan was deep in the process of the “Income doubling plan” formulated in the late 1950s by the government and bureaucrats to raise the income levels of all citizens. Part of it was political too – after 1960, tired of constant strife between labor and companies, and between students and conservatives, the government aimed to keep all its citizens happy through growth.

Thus, the government worked closely with large corporations, on the assumption that these companies would hire and retain a large cadre of middle-class office workers, to provide social stability. With the husband busy at work, middle-class women were excluded from the large companies, and assigned the role of domestic house manager, to manage family finances and to make sure that the children studied.

To fill these company positions, the education system underwent a large expansion. Children were socialized to study and take tests. Those who did well would go onto better high schools, where they were uniquely positioned to take exams and get into a good university and then into a good company.

Education based meritocracy and critique of the study system

One can see the layout if Nobita’s room in this clip from a movie adaptation of D

This is the setting of the Era of High Speed Growth (Kōdo seichōki, 1955 – 1973). To get ahead in life, Nobita must study. He has a creative mind but unfortunately, this creativity does not fit the examination system, which rewards rote memorization. Unlike the US, where it was possible in the 1960s to have a decent blue collar union job, there was no other path up in these East Asian societies that made it difficult for unions to operate. In fact, being a union leader could put you in jail or an early grave, as seen by anti-union governments in South Korea, China, Indonesia and Singapore.

Thus, for the lower middle class, children could move up by studying hard and entering a good university. Despite its harm to childhoods, this was the system adopted in places like Korea and China, and also in other developmental states like Thailand. Thus, in these societies, outside of the rare entrepreneur, there was no shortcut to studying. Following Japan’s developmental state success, and absent a culture of entrepreneurship, young children throughout eastern and southeastern Asia are taught that the only way up is through studying, doing well in school, entering a prestigious and competitive university through rigorous exams, and then entering a top rank company. No wonder mom is always nagging Nobita to study more! The Nobi family does not go on overseas vacations, or trips, showing that they barely make enough to maintain their lifestyle. All hopes are on Nobita to do well in school so that the family can rise up in society.

And yet, Nobita is a poor match for an exam system that rewards rote memorization, not creativity. In many nations like China or Korea, students compete to enter the “best” schools, based on grueling rote memorization exams. And the “best” students compete to enter the “best” colleges. In Korea in fact, the suneung college examination is so important that police help escort latecomers to the exam site, and flight schedules are adjusted so jet noises do not distract students.

No wonder Doraemon was a hit in developmental state nations in East and Southeast Asia! Post-war Japan's rapid economic growth served as a model for Asian nations in East and Southeast Asia. Although there were huge differences with the economic models, one constant remained: investment in education and sorting out winners and losers through an examination-based system. Of course, the wealthy could find ways for their children to succeed whether through inheriting family businesses or expensive private colleges.

But for middle and working class kids, a successful academic career led to social mobility. Thus many of Doraemon’s gadgets are a child’s fantasy designed to help with studying. When Nobita writes with the “ computer pencil,” it will come up with the correct answer on the test. Doraemon’s famous time machine can be used to move forward in time a week after the test, sneak into another student’s room and copy the perfect answers. Of course, Doraemon does his best to keep Nobita from cheating.

Young kids could relate to the education struggles of Nobita, known as Jin-gu in Korea or Dàxióng in Chinese. He is still a child, and so is lazy, does poorly on tests, and dreams of being outdoors. But his parents force him to study and the family 's future depends on his grades. This was the pressure that kids throughout Asia could understand regardless of language. Doraemon’s friendship with Nobita was something that they all wished they could have to relieve the stress of studying.

A shorter version of this post appeared in the June-July 2018 issue of Wasabi magazine.

Discussion Questions

- Who is Doraemon, and why does he live with Nobita?

- What makes the Nobi family an “average” Japanese family in the 1960s?

- Why do kids in Asia (like Vietnam or Indonesia) understand Doraemon’s world more than kids in the U.S.?

- How does Doraemon show the hopes and problems of families during times of fast economic growth?

- Can you think of a story in your country where a child uses magic or technology to solve problems?

- Do you think Doraemon’s popularity shows that many kids around the world share similar struggles like family pressure, school, and success? Why or why not?

Add new comment