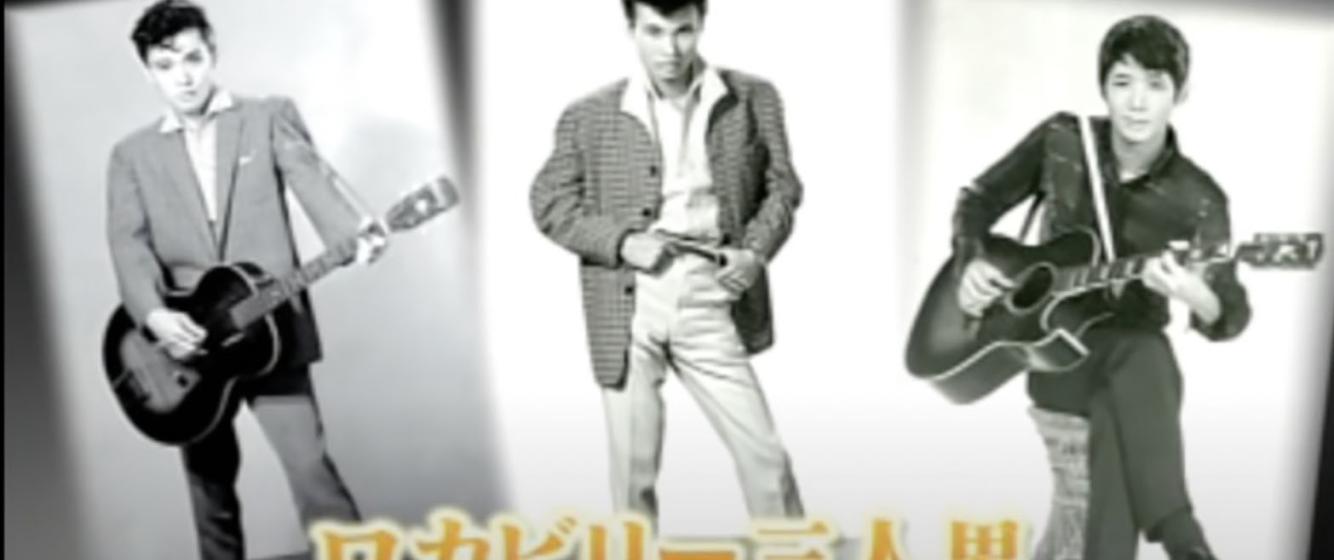

Bedlam at the Nichigeki Theater: The Japanese Rokabirī (rockabilly) craze of 1958

Prologue

In late 1957, Watanabe Misa, the manager for talent agency NabePro, was invited by her younger sister to a livehouse venue and saw crowds of young rockabilly fans.[1] Intrigued, Watanabe booked a series of concerts in February 1958 at the Nichigeki Theater, Japan’s largest performing venue. Among the many acts, rockers Yamashita Keijirō and Mickey Curtis performed with Hirao Masaaki in a trio dubbed by journalists as the Rokabirī san-nin otoko (Three Rockabilly Guys).[2] This was the first time the rockabilly artists would play in such a large venue, so the performers were nervous as to how the audience would react.

As recounted in an excerpt from Tobeta Makoto’s Birth of the Entertainment World (2022), in the early morning of the first concert, a crowd of mostly young teenage girls surrounded the Nichigeki in lines two or three deep. They stayed up all night and waited for the opening time, and some started dancing on the spot. Warned by a police officer about the crowds, Watanabe looked outside and said "Wow, that's amazing!"[3]

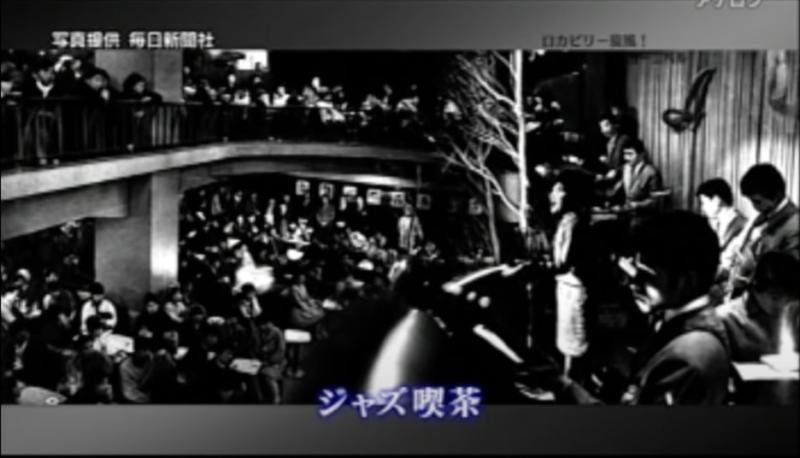

The Jazz Kissa (Jazz cafes) were the livehouses of the era and could seat hundreds of spectators. These cafes played a variety of music, including rockabilly.

The concerts shook the Japanese entertainment world. But rather than being a copy of American rockabilly, Japanese performers took American music, and learned, reconstructed, and improvised it on their own, thus laying the foundations for rokabirī, a hybrid of Japanese and American music culture. This music reflected the cultural power of America in the 1950s.

American music and Rokabirī Japan

By the mid-1950s, the Japanese economy had bounced back from wartime devastation. But for musicians, gigs at US bases became difficult to obtain, due to the decrease in US servicemen after the end of the Occupation in 1952. Therefore, musicians looked to venues outside bases to perform for the growing Japanese consumer class. One was the jazz kissa (jazz coffeehouse), large nightclubs seating hundreds of customers. Urban young adults gathered in the jazz kissa to hear the latest in music.[4]

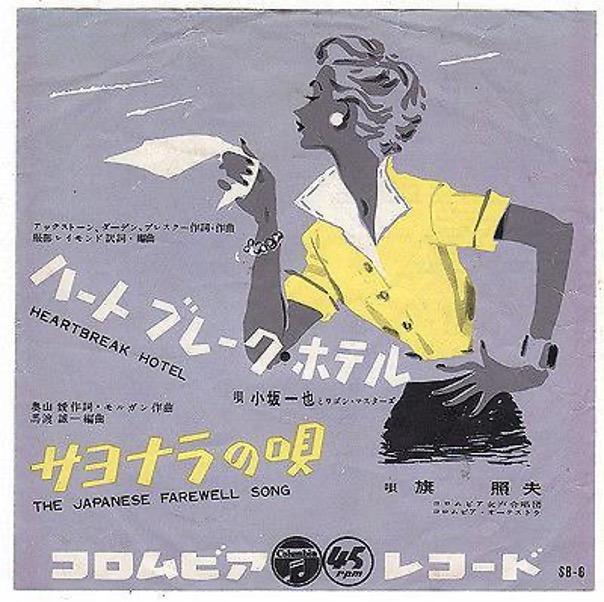

Kosaka Kazuya’s cover of “Heartbreak Hotel” was the first Japanese rockabilly hit.

Rokabirī in Japan followed the rockabilly scene in the United States. To many postwar Japanese urban youths, America symbolized emancipation. Thus, rockabilly music spread from American military bases to the urban youth subculture. However, Japanese rockers had to create their own version of rockabilly. Hirao reminisced in 2015 that he only had a fragmentary understanding of the fashion of his idols like Elvis Presley. Hirao’s band’s uniform was country and western, but wanting to stand out as the leader, he dressed differently in a bright red jacket, leading some people to call him a “fire engine”.[5] The appeal of rokabirī singers in the jazz kissa, according to a fan of Yamashita Keijiro, was like seeing a star before one’s eyes. Until then, stars could only be seen on the screen, so the “shock” of seeing these performers in person made her into a fan.[6]

Country music roots of rokabirī?

Michael Furmanovsky writes that many rokabirī artists were influenced by country bands of the early fifties in the bars around bases that catered to GIs from the rural and southern US.[7] This is not surprising since Elvis’s rockabilly was also a fusion of hilbilly music, blues, and black R&B. A Japanese country band, the “Wagon Masters,” were signed to Japan Columbia records and localized their songs to connect with audiences. They sang in both Japanese and English, with most of their songs translated and rewritten by Raymond Hattori, who studied music in Hawaii.[8]

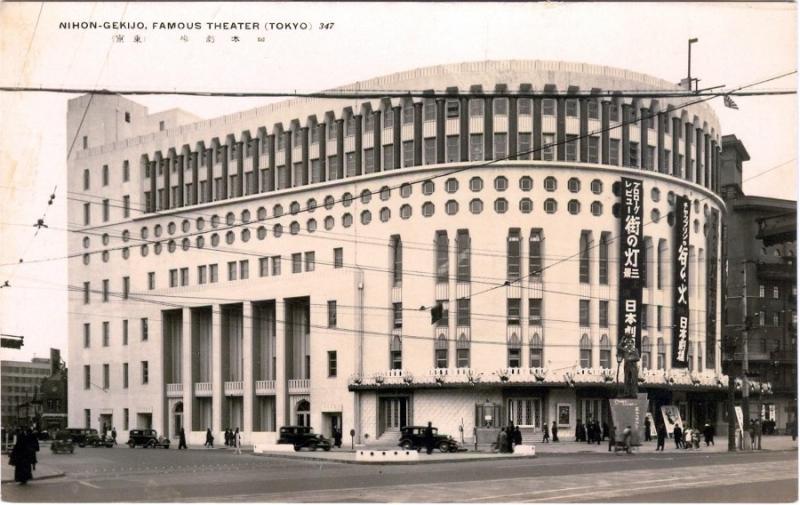

The Nichigeki Theater, the largest arena in Japan for its time.

Rockabilly landed in Japan in 1955, when the movie “Blackboard jungle” (1955), known in Japan as “Violence classroom” (Bōryoku kyōshitsu暴力教室), was released to parental criticism in Japan (as in America) with the theme song “Rock Around the Clock”(1955). Wagon Masters lead vocalist Kosaka Kazuya’s cover of “Heartbreak Hotel” (1956) with English and Japanese lyrics launched the rokabirī boom.[9] Shimizu Terumasa points out that songs were adaptations with the tunes, lyrics and phrasing changed to match the Japanese language. Often, composers would change the tune to fit the Japanese wording.[10]

Hirao, then a 17 year old high schooler who was secretly playing for a band at a US military camp, talked about the impact of the music: “The theme song “Rock around the clock” was decisive….I can’t forget the shock of the image accompanied by the beat of the music jumping into my eyes.”[11] However, he had no idea how to move on stage. Hirao, like other musicians, had to imagine an image based on the sound they heard. As he remarked in 2017, “At that time, there were few images and materials of Elvis, and movies didn’t enter Japan easily. I didn’t even know what he was wearing. I had no choice but to use my intuition. When I listened to his song, I thought ‘This is where he is singing while moving his body,’ or ‘He is playing with the guitar down’. His appearance flashed before my eyes, and I was creating Elvis in my own way.”[12]

Saxophonist on stage at the Nichigeki Western Carnival. Many of the performers never saw footage of a rockabilly concert so they had to guess poses based on album covers.

Enthusiastic fans (who were coached by the promoter’s sister) threw paper streamers and toilet paper (and sometimes panties) at the performers, ensnaring them in tangles of paper.

The Western Carnival had been held twice a year at a smaller venue sine 1954, specializing in country and western acts. Hori Takeo, who oversaw the carnival, wanted to bring rockabilly to a larger venue and asked Nabepro for help. Watanabe Shin, president of the agency, left the decision to his wife. Misa saw potential for daytime concerts to attract younger fans not allowed in jazz kissa at night.[13] Thus, she procured the Nichigeki Theatre to host the Carnival.

Bedlam on stage

This concert was a carefully crafted affair. Hori managed the selection of performers, the songs, order of groups appearances and sales. Also, Misa's younger sister instructed girls on how to cheer on the musicians.[14] Hori, who managed the event and performed as a member of Swing West, recalls the following story.[15] By dawn, the frenzy of the girls surrounding the Nichigeki was heating up even more. As a safety measure, the fans were let in two hours before the scheduled opening time, and girls rushed in, took their seats, and started cheering for their favorite singers before the performance started.

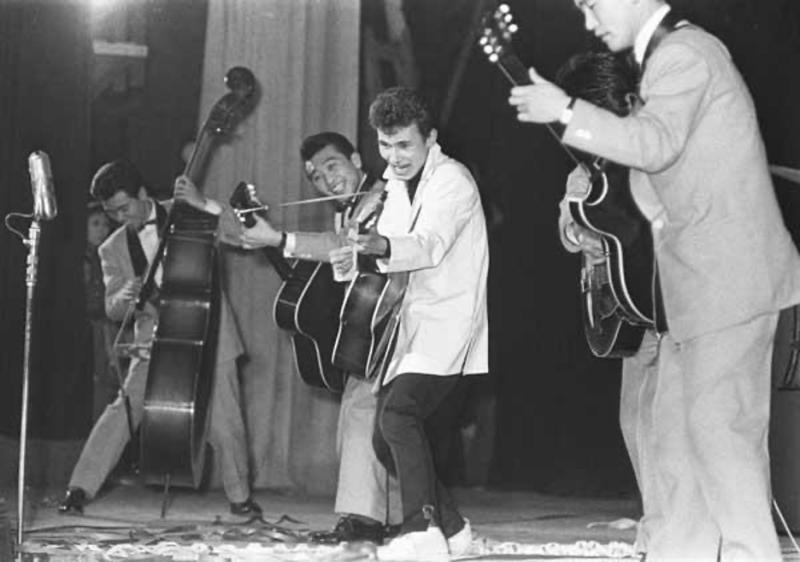

Mickey Curtis, one of the Rockabilly Three Guys, performing at the Western Carnival.

Hori recalls how the concert, a medley of covers of American songs, sent the fans into a frenzy. The singers struck unconventional poses, like playing the saxophone while lying on stage. The screaming girls in the audience overpowered the theater’s sound system, and so Yamashita, realizing that his voice was not loud enough to reach the fans, moved his body more violently than usual to express himself, causing even more mayhem among the girls. Throughout the concert, excited female fans threw thew paper streamers or toilet paper onto the stage, which got entangled in the musician’s guitars. Or threw their panties. Many of these girls were paid to whip up the crowd. Fans rushed the stage, dragged the singers down, and swarmed around them, kissing, hugging, and reaching for their crotches, leaving the musicians’ costumes in tatters.

The aftermath of the Western Carnival

Hori’s story shows how rokabirī unleashed the passions of their teen audiences. This rock festival was reported in the media, and huge numbers of audiences attended, exceeding 40,000 people in a week, a rarity for a time when there were no large-scale concert venues.[16] The Rockabilly Three Guys had become stars and Misa earned the nickname “rokabirī madam.” Little did they all realize that the rokabirī concerts would set off a moral panic fueled by the emerging medium of television. TO BE CONTINUED.

[1] NAKAMURA Toshio, “February 8 Is “Rockabilly Day" (2月8日は「ロカビリーの日」),” Otona no Music Calendar, February 8, 2016, http://music-calendar.jp/2016020801.

[2] Michael Furmanovsky, “Rokabirī, the "Western Carnival" and the Japanization of American Rock ‘n’ Roll Youth Culture,1957-62.” Presentation · September 2021 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.18892.74881

[3] TOBETA Makoto, “What is the legendary event "Nichigeki Western Carnival" that changed the entertainment world? "Birth of the entertainment world" trial reading” (“芸能界を大きく作り変えた伝説のイベント「日劇ウエスタン・カーニバル」とは?『芸能界誕生』試し読み: 試し読み,” Book Bang, December 23, 2022, https://www.bookbang.jp/article/742535.

[4] Yokohama Seven Channel, “Nichigeki Western Carnival (日劇ウェスタンカーニバル),” YouTube, January 18, 2011, https://youtu.be/rBfgwjN7-xE.

[5] “(Life's gift) My half-life Composer/singer, Masaaki Hirao: 3 77 years old,” Asahi Shimbun, December 16, p. 5.

[6] “Nichigeki Western Carnival (日劇ウェスタンカーニバル),” YouTube, January 18, 2011, https://youtu.be/rBfgwjN7-xE. 3:38.

[7] Michael Furmanovsky (2008), 'American Country Music in Japan: Lost Piece in the Popular Music History Puzzle', Popular Music and Society, 31:3, 357 — 372

[8] Michael Furmanovsky, “Rokabirī,” Student Radicalism and the Japanization of American Pop

Culture, 1955-60” (2007).; Furmonovsky, Furmanovsky, Rokabiri, the "Western Carnival" and the Japanization of American Rock ‘n’ Roll Youth Culture,1957-62. Presentation · September 2021.

[9] Furmanovsky (2008), 'American Country Music in Japan: 363-4.

[10] SHIMIZU Terumasa, “From Covers to Originals: “Rockabilly in 1956-1963,” essay, in Made in Japan: Studies in Popular Music, ed. Tōru Mitsui (New York, NY: Routledge, 2015), 103–19.

[11] SATO Tsuyoshi, “Remembrance, Masaaki Hirao, – 20-year-old Masaaki Hirao, who was the number one singer and the driving force behind the rockabilly boom,” Tap the Pop. July 23, 2017. https://www.tapthepop.net/extra/65054

[12] SATO, “Rememberance, Masaaki Hirao. https://www.tapthepop.net/extra/65054

[13] Furmanovsky, Rokabirī.

[14] Raymond Jones, “Vol 2 Advance to Nichigeki (Vol.2 日劇へ進出),” Retromedia, Yanaharuto Shoten (レトロメディア・囃ハルト商店), August 30, 2020, http://hayashiharuto.blog.jp/archives/82849401.html.

[15] TOBETA Makoto, “What is the legendary event "Nichigeki Western Carnival"

[16]CHŪJŌ Takanori, “What Is a Rockabilly Singer? The History of Japanese Rockabilly [50s and 60s] (ロカビリー歌手とは?日本のロカビリーの歴史【50~60年代】),” All About: hobby, April 13, 2023, https://allabout.co.jp/gm/gc/422444/.

Discussion Questions

- Who are the Rockabilly Three Guys and why was performing at the Nichigeki Theater a big deal?

- Why did Japanese teenagers like rockabilly music so much, even though it came from another country?

- How did Japanese rockabilly artists change the style so it worked better for Japanese audiences?

- If you were organizing a concert today of a foreign music genre for a local audience, what cultural elements would you include (language, clothing, stage, interaction) to make it meaningful?

- What does the rokabirī craze show about the power of youth culture in shaping music trends and challenging tradition?

- How do you feel about foreign influences in music and culture—does it enrich home culture, or risk overshadowing it? Can both things be true?

Add new comment