Asian Man, Black Woman (AMBW) and the K-pop and anime connection

In Part 1, the authors explored what is popularly known as AMBW (Asian Man, Black Woman), or BWAM (Black Woman, Asian Man) genre in some circles. This term exists in the context of Asian men and Black women in the U.S being perceived as the least attractive people on dating sites and in the media. AMBW fiction has become popular, portraying romances between couples of these ethnicities.

What can we unpack from the rise of AMBW fiction?

The following is part two of a conversation between Dr. Jayson Chun, a professor of history and co-editor of this Pop Pacific blog and Tawanza Farmer, an entering graduate student in Second Language Studies at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa.

1. Anime, K-pop and Black Women: the transpacific cultural fusion

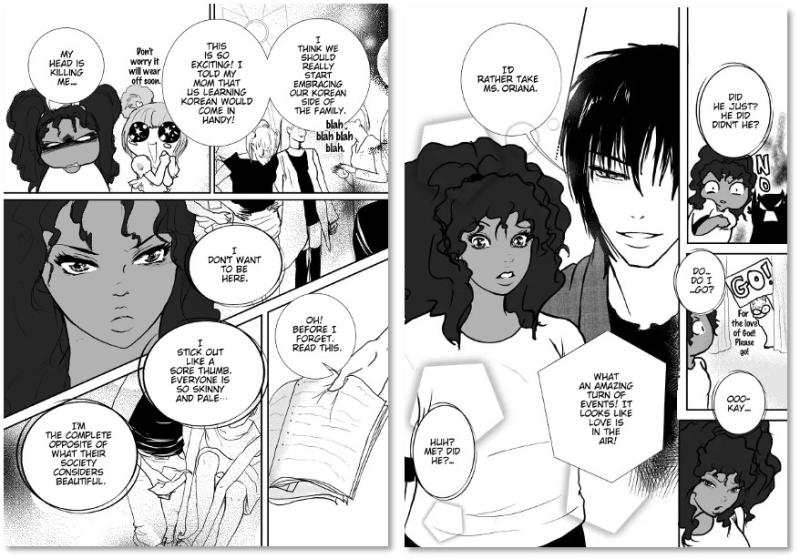

Sharean Morishita’s “Love! Love! Fighting!” shows Black female fans entering a pop culture fandom where they are often not accepted

Chun: AMBW genre reflects the intersection of African American influences in creating K-pop and the popularity of K-pop stars among Black women. So what is the role of K-pop and manga in creating AMBW?

Farmer: I believe it’s a similar cultural fusion where a generation of Black women that were raised on anime, and grew to like K-pop, want to occupy the fan space on equal footing. Lots of young Americans growing up in the 90s and early 2000s saw Dragon Ball Z, the iconic film Akira, Pokémon, Sailor Moon, and some still remember Kagome of Inuyasha saying “sit boy” in the Adult Swim dub. I was one of the younger kids (older Gen Z) who saw Pokémon and Sailor Moon after getting home from kindergarten. My older sibling and their generation (Millennials) were old enough to watch the cooler Adult Swim anime, and sometimes irresponsibly kind enough to let us watch it too.

Chun: Wow! I brought this up in an earlier blog post on how Generation Z is Japanese, since they grew up with shows like Pokémon as a natural part of their childhood!

Farmer: Yes, so if you have this generation of Americans watching Japanese cartoons, they’re having a “Japanese childhood.” Don’t most kids draw what they see a lot? As a result, these generations started drawing lots of anime-style things, popularizing shows they liked the characterization of, and criticizing ones with harmful stereotypes. They became Japanized in a way, and pretty much started creating an American form of doujinshi, self-made comics, and web novels; ranging from fanfiction to original fiction.

Black fans are actively involved in the anime community, making videos about Black characters in anime.

As for K-pop, it depends on when a fan becomes familiar with it in accordance with their age. If they’re a millennial or Gen Z that knew of K-pop before the 2010s, or a Gen Alpha that has grown up with K-pop, I think my statements will apply. These groups were exposed to enough of K-Culture that it became a part of their identity to consume K-idol media. As a result, they become deeply attached to the group, or soloist, they are a fan of. The whole basis of idol culture is built on the concept that idols require fan support to make it to success, so they expect fans to devote their all to them.

2. Webtoons, K-dramas and Asian males as the object of desire

_

AMBW fiction like in Sharean Morishita’s Love Love Fighting (center) allows Black female K-pop and anime fans to become part of a fandom, from which they are historically excluded

Chun: So why Asian men?

Farmer: In the steady consumption of all this media, it makes sense that the appeal of the men being portrayed in it increases. For anime, some of the most popular series amongst Black women are made by Japanese men for young men; that is, shōnen (boys) anime. Just look at Megan Thee Stallion’s Instagram and it becomes apparent from her anime posts and fan comments how many Black women like shōnen anime. Plus she’s a huge BTS Army fan! She collaborated with them, so famous fans like her and Lizzo are making a statement that it’s okay for Black women to be vocal about their love for Japanese and Korean media. Seeing your favorite Black American celebrity with your favorite Korean idol makes you feel like “it can happen”.

I actually want to argue that Korean dramas and webtoons are more influential on Black women than K-pop is. In K-dramas and webtoons, the plot is quite exaggerated, but there are several attractive Korean men that one can choose to be a fan of. It’s similar to an otome game like the popular mobile games: Mystic Messenger, Obey Me!, and Ikemen Sengoku. When it’s a K-drama, idols play the role of potential attractive partners, so they can either see them as more human or the “do-no-wrong" character. Black women growing up consuming this media, more than they do the American equivalent, will make the people depicted in it seem more appealing. Basically, Asian men.

_

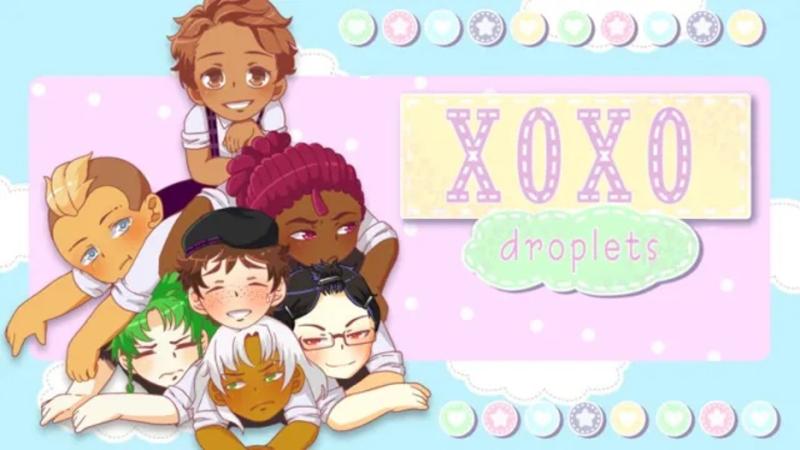

XOXO Droplets is an otome game set in high school and the protagonist is darker skinned than the usual otome heroine. Other games can be found here

As a Black woman, I don’t watch a lot of American shows because they aren’t inclusive. A show set in diverse metropolitan cities like Los Angeles and New York will only show White Americans, and when they do show Black Americans, they’re either comedic relief or violent plot devices. Korean shows have the luxury of being able to just show Koreans and still appeal to international audiences. We don’t get as upset because it’s not intentionally excluding prominent ethnic groups. It feels like a safe refuge for Black Americans, who always feel like second class citizens in our country, to watch the media in a foreign setting, because then we don’t have to fight for a space that should be ours.

Chun: Look at the impact that Asian media are having on the U.S., especially Black Americans! We talk about how much the US has affected Asia, and now we see how Asian media work with American racial dynamics to provide Black women with an alternate space of resistance.

In American society, Asians are neither white nor black, so they are safe for all races to idolize or ridicule. And unfortunately, the trend until recently was to ridicule. US media portrayals of Asian men mocked Asian male masculinity as seen in Ken Jeong’s stereotypical character of Mr. Chow, in the Hangover (2009). Jeff Yang, in response to the Asian stereotypes of the Hangover 2 (2011) called for Asian American audiences to support Asian American films and filmmakers who portray Asians positively.

3. Asian male as alternate soft masculinity

In many K-dramas, it is the male who chases the female.

Chun: This idea of Asian men as an object of desire has largely been absent in the mainstream US media. Until recently, it was rare to see Asian men in positive romantic portrayals in the US media, and much rarer to see Asian male and Asian female pairings. For example, the teen romance To All the Boys I Loved Before (2018), was based on a novel written by an Asian American woman and lauded for its Asian American female lead. Yet, there were dissenting voices about this series since not a single one of the five possible love interests was an Asian male, as seen in the trailer. This is part of a larger trend of US media featuring Asian women and White men as typical romantic pairings. As a result, American audiences (Asian Americans included) have been conditioned to accept White men and Asian women pairings as the ideal, and perhaps, the norm.

K-dramas, however, are unique in that they feature Asian men as the object of desire, as well as offer an alternative soft masculinity.

Farmer: In the fantasy of a K-drama, the masculinity of the male lead is rooted in how they treat their special person gently and consistently. He may say harsh words, but he’ll still give her special treatment. He may be inexpressive and distant with everyone else, but with her he’ll get upset or incredibly happy. He never cared who came or went from his life before, but now he even gets jealous thinking someone may take her away. It’s the opposite of the image of “struggle love” that defines lots of Black-focused romance media. It doesn’t demand that the woman persist through hardship caused by a male lead, get punished for being an overachiever, or told to settle and even abandon her dreams for love. The characters in K-drama also struggle, like us, but it’s rewarded generously. The female lead is often told to ask for more help and pursue her dreams unlike Black women are typically told. This creates an unconscious mindset that by virtue of this characterization, Korean, or other Asian men, are supportive and/or possessive of their partners. Possessiveness may seem undesirable in a realistic sense, but it is the backbone of American romance fiction. In a society where ghosting, situationships, casual hookups, and cheating are commonplace, American fiction focuses on constant communication, soulmates, consent, and possessive devotedness.

Chun: K-dramas and AMBW are an idealized media representation of Asian men, and as we pointed out in Part 1, we need to be careful of fetishizing each other. Male leads in romance novels represent a fictional ideal, not reality. My Korean friends are puzzled and ask me to explain why Korean men are so popular worldwide, and they laugh when I say they are seen as tender, expressive, devoted and affectionate, because many Korean men do not act like this in real life.

Still, K-drama romances, when viewed from a US perspective, normalizes handsome Korean men as the object of desire with an alternative masculinity. These are well-written romances with fleshed-out characters. As compared to American shows, these characters do not jump into bed quickly, and it often takes ten episodes before they kiss. And when they kiss, the K-drama male becomes a hot and passionate character. No wonder many women who like K-dramas and romance anime view Korean (and by extension Asian) men as the ideal lover - strong, loyal, sensitive, sweet, and hot!

Crazy Rich Asians performed poorly at the Asian box office because its selling point of an all Asian cast and Asian-to-Asian romance offered nothing new to Asian audiences.

In the US, Koreans are conflated with all Asians due to the general lack of representation of Asian men in the media. And Asian-to-Asian romances are generally non-existent. For example, Crazy Rich Asians was revolutionary in the US, mainly because it featured an Asian-to-Asian romance (although the handsome lead actor Henry Golding would be seen as an exotic, part-white love interest in Asia). It garnered an enthusiastic audience of Asian Americans and Americans in general who made this movie a financial hit.

But Crazy Rich Asians (set in Singapore) did poorly in places like China or Korea - the selling point of an predominantly Asian cast, with an Asian-to-Asian romance, while unique in the US, offered nothing new to Asian audiences. Audiences in Asia are used to the norm of Asian men as love interests, so there was nothing revolutionary about Crazy Rich Asians.

Romantic portrayals featuring Asian men are the norm in Asia, such as in K-pop videos like “Spring Love” (2016) with Atlanta-born Eric Nam.

Even in K-pop music videos, romantic portrayals between Asians are the norm, such as Atlanta-born Eric Nam with Wendy Shon (who went to middle school and high school in the US and Canada) of Red Velvet, in the video “Spring Love (2016).

4. AMBW as a means of Black female fan empowerment

Chun: Is this a creative outlet for Black women? The AMBW genre seems to be aimed at Black women rather than Asian men. Romance is one of the top genres in novels, TV, movies, manga - almost any storytelling media in the U.S.. The romance audience is dominated by female consumers, and this would help explain why Asian men may not be big readers of AMBW. So this genre allows Black women to imagine themselves in a relationship usually not seen in the Western media.

Farmer: Maybe, thanks to the rise in anime and K-pop, Black women are adding to the AMBW genre with their creative contributions. TeenVogue said it best: “In K-pop fandoms spaces, Black women are told that the idols we adore could never actually want us. In anime fandom, we are called slurs for cosplaying popular characters. Black fans in general aren't seen as part of fandom[...]” So while the interest Black women have in Asian culture and men is increasing due to globalization, they can’t show it in fan spaces without being attacked. They channel that desire and expression in the AMBW genre. It becomes a safe space where childhood exposure to Asian media, unmet social desire, and the need to be loved meet to create a genre where Black women can have it all. The ‘all’ being: an attractive, witty, and thoughtful Asian man, a beautiful, confident, and respected Black woman, and a love that centers and empowers both people. It liberates them from being the side characters.

Chun: Well said! This marginalization of Black fans is one of the sadder aspects of K-pop and anime fandom, which I hope AMBW can continue to address. This is ironic especially since Black culture is woven into the roots of K-pop. Let's continue this idea of the Black roots of K-pop and AMBW as a way for Black women to assert their identity in a place they are unfortunately often excluded: K-pop and anime fandom. So off to another post!

Thanks to Dr Sharon Woodlief for her helpful comments and edits.

Discussion Questions

- What does “AMBW” stand for, and what has contributed to its popularity?

- How did anime and K-pop help shape the AMBW genre, according to the authors?

- Why might AMBW fiction be especially meaningful or empowering for Black women?

- What problem might happen if AMBW stories only use stereotypes?

- Can you think of another example from your culture where two groups who usually aren't shown together are paired in stories?

- How can fan-created stories like AMBW help people feel seen and connected?

- What does AMBW's popularity tell us about culture today?

- When we tell or read stories about other cultures, why is it important to be respectful?

Comments

Awesome Blog

I love the AMBW blog it’s so awesome. Please keep sharing.

Add new comment