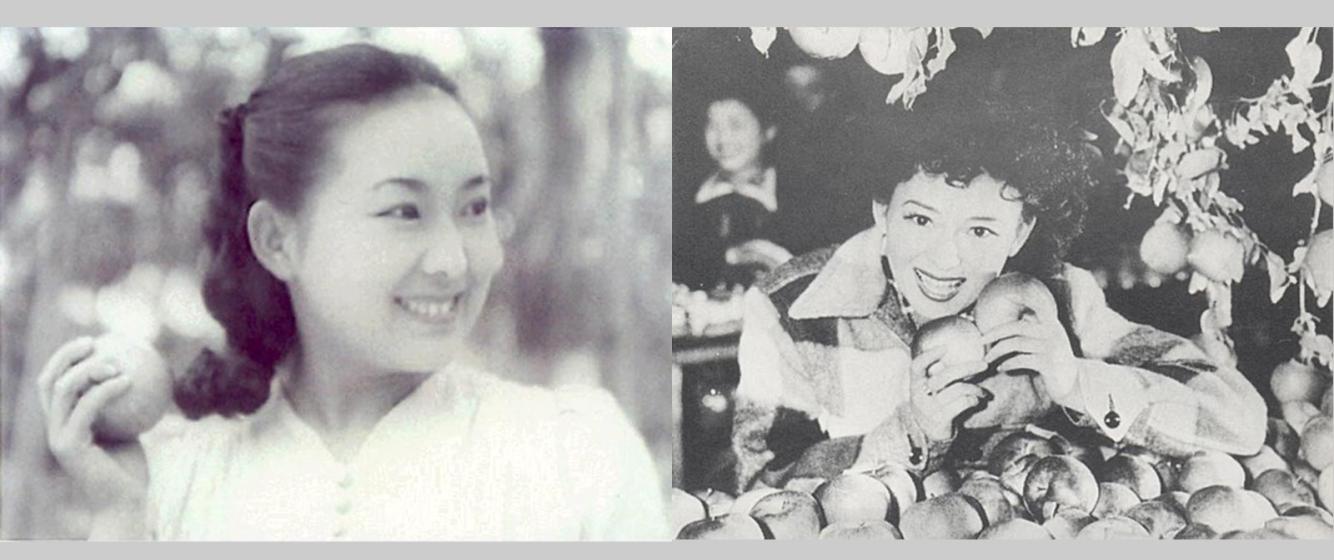

Namiki Michiko, singer of “ringo no uta” (1945) in the movie Soyokaze (1945), and in 1946. Public domain.

Apples, boogie and shamisen: A Brief look at Japanese Popular Music during the Allied Occupation

Bringing the red apple to my lips

Staring at the blue sky in silence

The apple says nothing

But I understand what the apple feels

The adorable apple

The adorable apple

What a difference ten years makes! These were the lyrics to "The Apple Song” (Ringo no uta, 1946), the first postwar popular song in Japan. Featured in a 1945 film, the song was performed as a duet by singer Noboru Kirishima and actress Michiko Namiki and later released as a recording in 1946. This bouncy song was seemingly about a red apple, but the lyrics captured a girl's emotion from the sense of liberation after the war. Compare this song to If I go to sea (Umi Yukaba, 1937), a wartime song glorifying one’s sacrifice to the emperor, and sung by kamikaze pilots before their one way suicide missions.

If I go away to the sea,

I shall be a corpse washed up.

If I go away to the mountain,

I shall be a corpse in the grass

But if I die for the Emperor,

It will not be a regret.

Life had changed so much after the war that a song about an apple, rather than a patriotic wartime song, commanded nationwide popularity. Although the “Ringo no Uta” lyrics were full of hope, Namiki found it difficult to sing this happy song because of the deaths of her mother in the Tokyo air raids in 1945, her father and brother when their ship was torpedoed by a US submarine, and her boyfriend when he undertook a mission as a kamikaze pilot. Like many Japanese, she forced a smile and sang a happy song to look ahead to the future.

This song also represented the mishmash of songs that came out under the influence of American-dominated Allied Occupation censors, who attempted to steer Japan away from its prewar culture and towards an American-influenced one. After Japan's unconditional surrender in August 1945, Occupation forces entered the defeated country and enacted reforms to curtail military power. These officials banned military songs while encouraging songs like “Ringo no Uta” However, with the rise of Communism in East Asia, the Allied Occupation by 1948 deemphasized reforms to concentrate on Japan's economic recovery. Thus, the old system lived alongside the newer reforms, and this was reflected in the mix of old, new songs and hybridized popular outside the bases.

Japanese music during the Occupation, like “Ringo no Uta” represented a curious hybrid of Japanized Western songs with interesting titles and sounds. US military bases played a key role in postwar Japanese popular music as residents of urban areas came into direct contact with American military personnel, and jazz from the bases flowed to the cities. The radio station Far East Network (FEN) began broadcasting in September 1945 for occupation soldiers, but Japanese listeners could tune in and listen to the latest American popular music.[1]

Public Domain

Shizuko Kasagi (1914–85) in the motion picture Ginza Can-Can Musume (1949).

Kasagi Shizuko’s “Tokyo Boogie Woogie” (1947), written by songwriter Hattori Ryoichi, if released only a few years earlier, would have been censored for being too Western. A jazz singer in the 1930s, she continued her career with the lifting of imperial era censorship controls (replaced with Occupation era censorship controls). According to a rather insulting August 1949 Time magazine article, Hattori wrote this song when he saw Japanese couples trying to jitterbug to the melancholic blues most Japanese composers were writing and decided "to break away from kurai ongaku [dark music].” Michael Bordaughs recounts the famous story of how Hattori got the inspiration for “Tokyo Boogie Woogie” while riding a train and listening to the to the rhythm of the rails and slapping of overhead hand straps that matched the rhythm of the boogie-woogie style. Kasagi also appeared in a scene Kurosawa Akira’s classic Drunken Angel (1948). In this movie, she gave a frenzied performance of “Jungle Boogie”(1948) also written by Hattori, engaging with a call-and-response typical of African American jazz with her all-male orchestra.[2]

Screenshot of Kasagi Shizuko performing “Jungle Boogie” (1949) in the movie Drunken Angel (1949)

Kasagi’s song set off a nationwide boogie craze. In a unique hybrid of jazz and Japanese music, the geisha singer Ichimaru released “Shamisen Boogie-woogie”(1949). Born as Matsue Goto, she became a geisha trainee at 16 years old. Her beauty and singing skills made her famous, and so she was signed by the Victor Recording Company and debuted in 1931 and later became a full time singer. With the end of the war, she became interested in jazz, and composer Ryouichi Hattori wrote “Shamisen Boogie-woogie” for her. [3] This song is an interesting mix of the shamisen, an Okinawan string instrument traditionally played by geisha, with American swing jazz.

Public domain

Geisha-turned-singer Ichimaru, singer of “Shamisen Boogie-woogie” (1949).

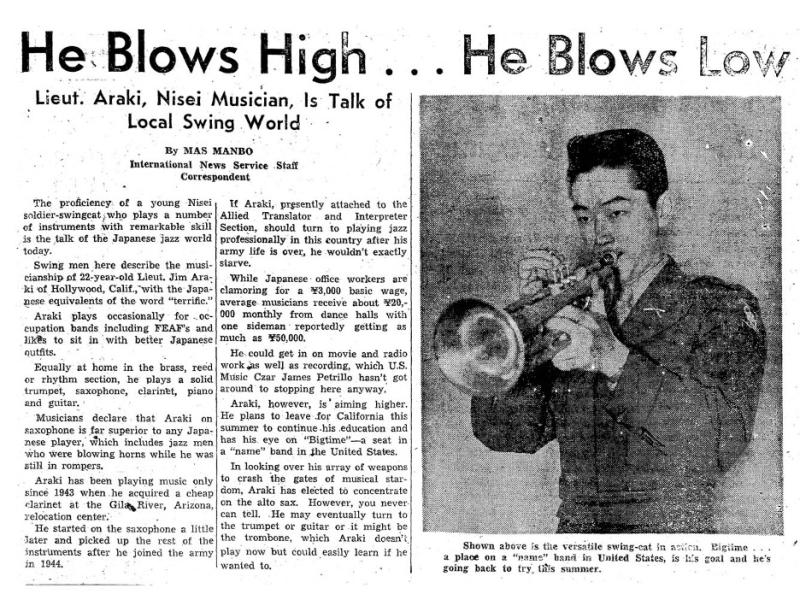

Like in the interwar era, Japanese American sojourners played a key part in the spread of a hybrid music culture to Japan. They came as U.S military linguists, as their knowledge of the Japanese language made them valuable interpreters for the Occupation and allowed them to interact with Japanese. For example, as seen in a fascinating Discover Nikkei article by Jonathan van Harmelen, saxophonist and trumpeter James “Jimmy” Araki (1926-1992) introduced bebop jazz to Japan. During the WWII internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans in the US, Araki performed in internment camp bands as a teenager. Later, he served in the US Army as a translator. In his spare time he introduced bebop jazz to Japanese musicians and played a key role in the first "modern jazz" recording session in Japan in 1947. In “Jimmy’s Bop” (1949) one can hear Araki playing with Japanese and western musicians.

Postwar cultural influences went in both directions, as famous Japanese singers such as Misora Hibari, or Kasagi Shizuko performed for Japanese Americans in Hawaii and the West Coast cities. As Christine Yano notes, these performances also influenced local Japanese American communities, by allowing members to rally around these Japanese stars and express their ties to Japan.[4]

The Occupation ended in 1952, except for Okinawans, who lived under American military rule until 1972. The American presence was gradually reduced throughout the following decades, although bases remained on Japanese soil. The legacy of the Occupation lived on, as American style and hybridized popular music spread into the mainstream. As we shall see, television would help spread this music throughout the nation in the 1960s.

[1] Toru Mitsui, “Interactions of Imported and Indigenous Musics in Japan: A Historical Overview of the Music Industry,” In Whose Master's Voice?: The Development of Popular Music in Thirteen Cultures. Alison J. Ewbank, Fouli T. Papageorgiou. Greenwood Publishing Group, Jan 1, 1997. Pp. 152 - 174. P. 166

[2] Bourdaghs, Michael. Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon : A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop, Columbia University Press, 2012. 31.

[3] Remi Kobayashi “The Shamisen Boogie Woogie, Exploring The Life of Ichimaru,” Nikkei Voice, Jan 16, 2014. “ http://nikkeivoice.ca/the-shamisen-boogie-woogie-exploring-the-life-of-…

[4] Christine Yano, Crowning the Nice Girl: Gender, Ethnicity, and Culture in Hawaii’s Cherry Blossom Festival. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006): 42 – 44.

Discussion Questions

- What was “Ringo no Uta” (The Apple Song), and why was it important just after WWII?

- Why did American occupation authorities ban military songs but allow or encourage songs like Ringo no Uta? What effect did that have on what people listened to?

- How did U.S. military bases and things like the Far East Network radio shape the musical tastes of Japanese people during the Occupation?

- Can you think of a song in your country that mixes local and foreign music styles?

- How might radio or modern media (like TikTok) play a similar role today as FEN (Far East Network) did after WWII in spreading foreign songs?

Add new comment