Attack on Titan Cosplayers - MCM Comic Con, London 2016. Public Domain. CC BY 2.0 by Altan Dilan

Attack on Titan (2014): Examining 21st Century Global Youth Through Anime

Many people, if they want to understand Japan, take college classes, martial arts, or study the religion. For me? I prefer to watch anime. How about giant emotionless humanoids that devour people by snapping them in half like a snack (Attack on Titan)? Or a bald hero who can destroy with a single punch (One-Punch Man)? Let’s go back to the 1990s and watch young and emotionally troubled teenagers forced to pilot giant robots to ward off an alien invasion (Neon-Genesis Evangelion). What about a smash hit about a girl and a boy who swap bodies (Your Name)? Watching “recent past” anime from a decade ago retrospectively shows the hopes, fears, and dreams of young adults in today’s Japan. Enough time has elapsed that we can discern these ideas that may not have been apparent on first viewing. And given the popularity of anime among youth worldwide, they show that today’s youth across the globe often face similar fears and dreams.

Anime can be considered the more commercial variant of manga, the comics of Japan. Manga, being relatively cheap to create but potentially able to garner considerable profits, is relatively easy for mangaka (manga artists) to create. Successful manga is often turned into anime that will run on television or online. There are many popular anime—for example, the king of anime is the long-running One Piece, which debuted as a manga in 1997 and as an anime TV series in 1999 (with over 1,000 episodes). This series can tell a lot about Japan until you realize most of its initial fans are now in their forties, and it tells you more about what their generation has experienced.

Manga, because it is cheap to produce, can be expansive and wild in its explorations of themes that resonate with youth. Anime, because it requires more labor and is more costly, must play it relatively safe. Therefore, anime will often be adapted from popular manga, but editors and anime committees must make sure that the anime turns a profit, and therefore they tone down possibly controversial material. Often, this means formulaic anime, but if one has a discerning eye, one can still see the thoughts, fears, and dreams of Japanese youth.

But now, with the global popularity of anime and manga, these popular culture products can be considered transpacific, and reflect youth worldwide. Such is how our global generations have intersected.

Beginnings of a class on anime

.

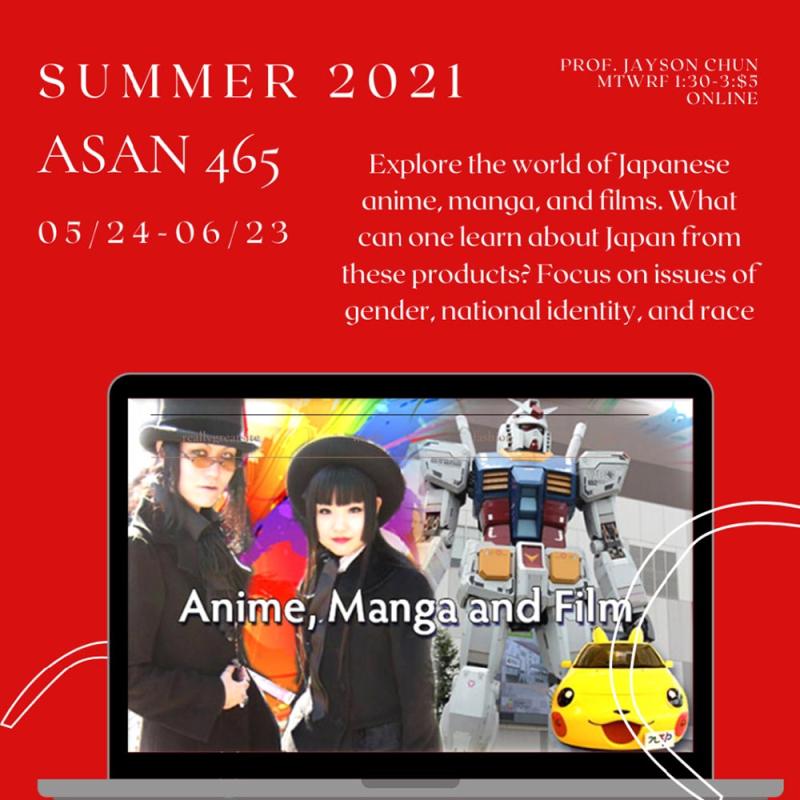

Flyer using public domain images to advertise my anime class University of Hawaii at Mānoa (2021)

I remember back in 2003, when I was a lecturer at a small liberal arts college in the Pacific Northwest in the US.. Three young students came to me and asked if I could do an independent study for them since the professor was on sabbatical. I said sure and what topic, and one of them said, “you really want to know?” Then they told me, “Anime.” My eyes opened up because I had been an anime fan in the 1970s and 1980s, and here I was with the opportunity to explain Japan through a medium that I had grown up with, but had no one to share.

Growing up in Hawaii in the 1970s, and on visits to relatives in Hiroshima, I was exposed to anime. I had no idea what the cartoons on tv were saying, but I was mesmerized by them, for example a guy with sunglasses and a yellow talking frog on his T-shirt. I brought manga home, and painstakingly translated them using a dictionary. But alas, there were few others with whom to share manga and anime. I went through high school and college in the 1980s with no one to talk to about these products.

In the early 2000s I realized that anime and manga had suddenly become mainstream. Of course, I designed an independent study curriculum for these students based on anime and manga which was appearing on American cable tv at the time. And I remember going in 2003 to Springfield, Oregon, a blue-collar town to speak to middle schoolers about anime. I thought this would be an easy lecture until I asked “who knows about anime?” Everyone raised their hands, excitedly saying, “me me!!” Then I realized these students knew more about recent manga and anime than I did. Such was the power of Toonami on Adult Swim (what are kids doing watching “Adult” swim??) on the Cartoon Network. These students are in their mid-thirties now and their kids are probably watching anime.

These experiences led me to teach my first course on Japanese anime in 2005 at the University of Hawaii summer school. Interest in Japanese popular culture was so high that many of our discussions led to talk about J-pop, the Japanese pop music that was often tied in with Japanese anime. So I started teaching a class on that, too, and with the growth of K-pop, expanded the class to include that topic too. These classes are still running every summer twenty years later.

Anime as the local and the global

.

"Attack on Titan" cosplayers at the 34th Asian Animation Creation Exhibition (Tokyo, 2021) User:玄史生 - Wikimedia Commons

Some anime—sometimes, the dark and obscure (or in some cases, non-obscure)—will show you what young people are thinking both in Japan and the world. I find that students in my anime class in Hawaii can easily catch on to anime themes because they relate to the students' fears and dreams, even in a different culture.

For example, in the epic Attack on Titan, which ran as an anime from 2013 to 2023, humanity is on the brink of extinction, with humans hunted as food by giant humanoid monsters known as Titans. The remnants of Earth’s population have retreated behind a series of massive walls and struggle to keep these hellish creatures at bay. The story follows Eren, his adoptive sister Mikasa, and his friend Armin—three teenagers who survived a deadly attack by a Colossus Titan years earlier and have vowed revenge. As a member of the elite Survey Corps, whose responsibility it is to venture out into Titan-held lands to find out more about their enemy, Eren begins to discover that he may actually be the key to mankind’s survival. Along the way, viewers are treated to an incredible body count—many die a slow and grisly death on screen, showing the stakes of failure in this hyper-competitive world. In this multi-year epic, which examined issues like corruption, youth job competition, social inequality, militarism and nationalism, the youth die fighting the Titans while the incompetent adults live safely within the walled city. They are in the predicament of fighting because the adults failed to protect them from the Titan attack in the first place, leading to the devastation of much of the city and the slaughter of people. The message to young viewers is that adults have screwed up. Whether it is the economy or society, something is wrong, and guess who pays the price? It is the young ones who must die fighting while the older ones are protected.

But this was not a new theme—two generations earlier in the giant robot franchise Gundam, which started in 1979, teenagers are expected to fight off a threat to humanity. And they are the only ones who can do so and thus the ones sacrificed. What has changed is the context; the world of 1979 was far different from the world of the early 21st century. In 1979, Japan was a rising power, seen as possibly surpassing the United States as the world economic leader. In 2009, when the Attack on Titan manga began being published, Japan found itself amid a still ongoing decades-long economic slowdown, which gave rise to a new generation: what I would like to call the “post-post-bubble generation” (P2 Generation). Just like Isayama Hajime, the author of this manga born in 1986, this generation was born around the time of the collapse of the economic bubble, so had no knowledge of the high-growth years of their parents. While this generation saw glimmers of hope in increased hiring due to the declining birth rate, they also had to face a Japan that was being increasingly eclipsed by China and South Korea in certain industries. And they also faced hyper-competition at home for entry into stable employment at large corporations.

“Recent past” anime from the 2000s and 2010s shows that the generation shares a lot in common with youth worldwide, and that is why much of its anime rings true with youth facing hypercompetition for jobs and grim job prospects. Attack on Titan was highly popular in Korea, despite the Japanese nationalist overtones and much worse relations with Japan than today. Korean youth see intense competition for college, and lowered job prospects in their “Hell Joseon”. Chinese youth are confronted with grim job prospects after surviving the competitions of college, and if they do get a low-paying job that demands from them a “996” work culture (work from 9 to 9, six days a week). In the United States, the majority of Generation Z men (born after 2000) without college degrees, facing grim job prospects and uncertainty, voted overwhelmingly (67%) for Donald Trump.

The global popularity of Attack on Titan in the 2010s foreshadowed a rightward turn among many youth worldwide, driven by the grim economic outlook and desire for an authoritarian and militaristic leader to save them. People who were paying attention to anime could easily see the appeal of these kinds of leaders.

Anime can tell us a lot about youth. Future articles will explore the past, “recent past” and currently popular anime and manga and what it says about the youth generation in Japan and Gen Z worldwide.

This blog post is based on an article published in Wasabi Magazine, Issue 1 Vol 4 Oct-Nov.

Discussion Questions

- What does the author argue anime and manga can reveal about Japanese youth and global youth culture?

- In Attack on Titan, why are teenagers the ones forced to fight while adults remain safe? How might this story reflect young people’s views of society?

- The author suggests anime reflects youth frustration with job competition and limited opportunities. Do you think anime (or other media) can actually shape how young people view their future, or does it just mirror reality?

- The author links the popularity of Attack on Titan to global youth frustrations—such as “Hell Joseon” in Korea or “996” work culture in China. Can you think of examples in your own country or culture where entertainment reflects similar frustrations?

- The article argues anime can foreshadow political and social trends, such as youth turning toward authoritarian leaders. Do you think popular culture is a good predictor of political change? Why or why not?

Add new comment