Shanghai: The 1930s, Jazz, and Popular Music in “The Paris of the East”

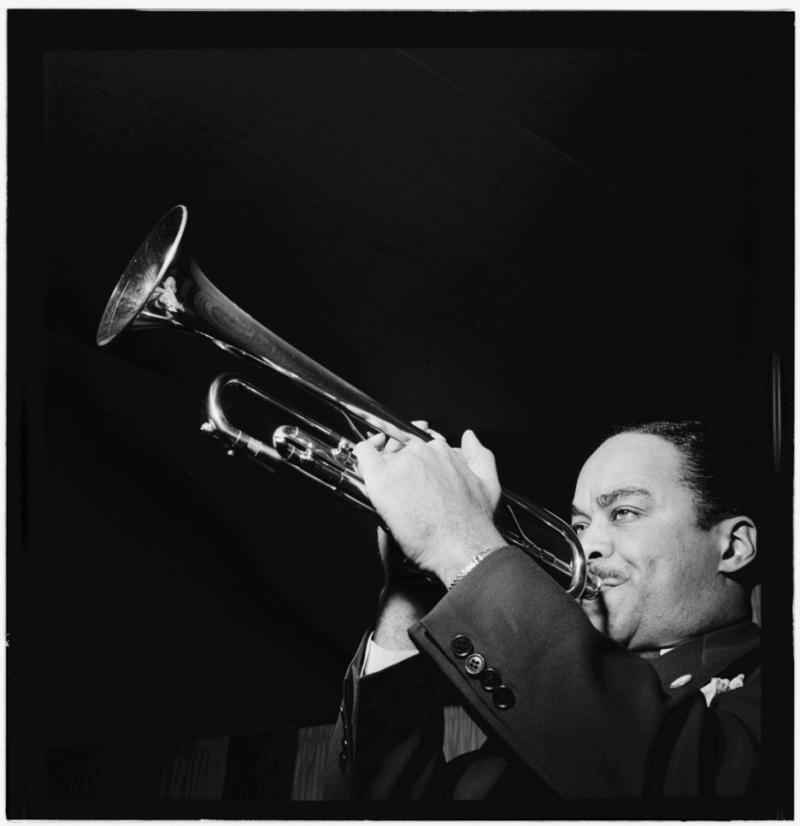

In 1935 the legendary Buck Clayton, a Jazz trumpeter from New Orleans with Native American and Black roots, stepped off a steamer in Shanghai. He’d been recruited by stride pianist Teddy Weatherford, himself worthy of a place among the Jazz apostles who spread the music to Asia. Clayton was there to lead an orchestra known as the Harlem Gentlemen at a posh club called the Canidrome, a massive night-club-cum-casino so-named, according to Clayton in his autobiography, for its association with the dog-racing track on the same property. It was large, like an aerodrome, and supported canine racing. Weatherford played there already and was also in charge of finding artists for the club, which was frequented by wealthy Chinese businesspeople and European, American, and Japanese expatriates. He recruited the Harlem Gentlemen to back him up.

The irony of their situation was not lost on Buck Clayton and his band. They had gained entry into the world of Shanghai’s rich and famous - Madame Chiang Kai-shek attended their opening show along with her sister - and were paid well for their work. Clayton and the boys bought tailored suits and lived a life they could not have had back home in the United States, yet they were still reminded - by the abject poverty of the majority of Chinese they saw, and by racist taunting and brawls brought by U.S. Marines stationed in the city, of the realities of Imperialism and their own social position “at home.” In fact, their successful self-defense in at least one brawl led to a lawsuit and the eventual cancellation of their contract at the Canidrome. Stuck in Shanghai, several band members, including Clayton, took work at a more locally-oriented night club, where to be successful, they also needed to learn to play Chinese popular songs. This led Clayton to learn to play the songs of Li Jinui, Shanghai’s famous composer and entrepreneur, with whom he eventually also collaborated. Returning to the United States just two weeks before the Japanese invaded Shanghai in 1937, Clayton played Li’s and his songs back home as well in a clear example of American-inspired Chinese Jazz coming back to re-inspire changes in American Jazz.

Many of the technological, musicological, and economic patterns that make up the Pop Pacific today came, like they did for both Buck Clayton and Li Jinhui, the father of Chinese popular music (and of Chinese Jazz), from “contact zone” cities before World War II. In the early twentieth century, some contact zones were colonial capitals (Keijo/Seoul, Manila), and others were newer modern urban cores (Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore) with developing middle classes and varying degrees of foreign influence. Shanghai was economically important enough to draw an artist of Clayton’s caliber and populated with people who wanted to hear him. Its own racial and economic divisions were different enough from those in the United States that Clayton and the Harlem Gentlemen had opportunities to meet and play with the elite in Chinese Jazz and popular song circles. This is one of the draws of an international city - fortunate connections that change the world.

Shanghai, “The Paris of the East”, aka “The Pearl of the Orient” was the most international, complex and influential contact zone in Asia during the 1920s and 1930s. This city was a center of global jazz and popular music influences,due to a combination of European, American, and Japanese imperialism, sinceChina was never colonized, but carved into zones of influence subject to foreign law), and to international trade, and a multicultural network of artists and entrepreneurs. Here American Jazz musicians like Teddy Weatherford and Buck Clayton met and played with Chinese musicians and composers such as Li Jinhui, and Japanese musicians including Hattori Ryoichi. Shanghai changed music in Asia in many ways.* Shanghai’s open culture before World War II, the diversity of people, cultures, and music represented, opened the way for foreign influences and created a market for popular songs. Li Jinhui, composer and impresario, wrote jazz and popular songs, learned from musicians of all kinds in Shanghai, and in the 1920s created China’s first “girl group” the “Bright Moon Song and Dance Troupe.” He created the group to showcase his own songs, and to fund his performing arts high school, but also because of his desire to promote Mandarin as a standard language for Chinese. He took them on the road to Southeast Asia, playing in Chinese diasporic communities, to promote both Mandarin and a Chinese national identity that, he hoped, would counter Japan’s growing power in Asia. Li’s music, concentrating as much popular music does on love, relationships, and romance came to be seen as lascivious by his student and critic Nie Er, by socialists and Chinese nationalists, and by the nascent Chinese Communist Party. All of these groups eventually branded it “Yellow Music,” which defined it as “pornographic songs” to discredit it. But much of it remains popular to this day, built as it was on a foundation of international influences and Chinese tastes.[1]

In many ways, Shanghai became the Hollywood of East Asia. There, a confluence of popular musicians, record companies, and film studios fed off of a freewheeling financial culture. The city was home to a diverse population of Chinese, Japanese, and Western entrepreneurs, government representatives, and wealthy sojourners, and therefore gave rise to the entertainment culture that supported their desires and habits. Like Chicago, Shanghai in the 1900s to the 1930s was home to an infamous gang culture whose legendary feuds and larger-than-life personalities cut a romantic image that overlay their tawdry dealings in opium, sex, and gambling. Shanghai was where, in 1927, Nationalist leader Jiang Jieshi and the infamous Green Gang chose to begin the purge of the Chinese Communist Party, partly because its commercial modernity and thriving industry made it a hotbed of union and Communist activity, and partly because its entrepreneurs provided his Party with funding and a capitalist/entrepreneurial political base. The lights, buildings, and energy of the famous “Bund” waterfront district fed the world an image of Shanghai as an international city to rival Paris, London, New York, and Chicago. This was a key contact zone where musicians learned from each other about the newest musical ideas, and created, together, the “next thing” in Asia.

For Buck Clayton, Shanghai served as one of the cradles of his eventual fame. He went on to play first with the Count Basie Orchestra, and then with his own group. He is a legend in the United States Jazz world. When he went to Shanghai, he was unaware of its growing status, which he helped to build, as the Jazz capital of Asia. Shanghai, he found, was a contact zone in which music and musicians from around the world met and learned from each other. This was the essence of the Pop Pacific - one of the most active zones of contact and artistic transfer.

Bibliography

Atkins, E. T. (2001). Chapter 2: The Soundtrack of Modern Life: Japan's Jazz Revolution. In Blue Nippon Authenticating Jazz in Japan (p. 91). essay, Duke University Press.

Jones, Andrew F., “Black Internationale: Notes on the Chinese Jazz Age.,” in Jazz Planet (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 225–43.

Jones, A. F. (2006). Yellow Music: Media Culture and colonial modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age. Duke University Press.

Quirino, R. C. (2004). Pinoy Jazz Traditions. Published and exclusively distributed by Anvil.

[1] Jones, A. F. (2006). Yellow Music: Media Culture and colonial modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age. Duke University Press.

Add new comment