Prewar Transnational Pop Stars

A Japanese national who posed as a Chinese singer during wartime, a Tokyo-trained modern dancer from colonized Korea who enjoyed huge popularity in Japan and even toured the United States, and a young Japanese-American Broadway singer-dancer who gained popularity as a jazz singer in Japan. These three entertainers exemplify the Pop Pacific. Yamaguchi Yoshiko, Choi Seung-Hee, and Alice Fumiko Kawabata pioneered the pop genre before the Second World War. Rather than sharing nationality, they shared status as early transnational music icons and the popular music industry that made them. All three performed as border-crossing, code-switching celebrities who embodied the prewar Pop Pacific.

As my next few posts will show, twentieth-century prewar popular music in the Asia Pacific never belonged to a single culture – it was always a mix. Moreover, the popular music industries in Japan, China, and Korea developed together in the pre-World War II era. They were co-dependent, both on each other and on the common development and distribution of music recording and playback technology. Much of what we think of as Asian popular music today can be traced back to the patterns of market identification, song lyrics, and musical styles designed in the early twentieth century, and epitomized by the recordings and performances of these three women. In this post, I will start by talking about them, because they were the most visible element of popular music - the pop stars of the prewar period.

Choi Seung-hee

In 1939, wildly popular Chinese singer Li Xianglan (known in Japan as Ri Koran, the Japanese pronunciation of her Chinese name) traveled to Japan from her home in Manchuria to give a concert. Upon disembarking from her ship, a Japanese Immigration Official took a look at her documents and realized her real name and identity: a Japanese citizen named Yamaguchi Yoshiko. He shouted angrily at her that she should show pride in her native country and culture by not wearing the Chinese fashions she had on, but a proper Japanese kimono. He eventually allowed her through, and the concert sold out. Her trials were only then beginning. At the end of Japan’s occupation of China, in 1945, the Chinese government arrested Ri Koran and charged her with treason because she had appeared in a number of films that they said encouraged the Chinese to accept Japanese rule. She faced the death penalty until a friend from Manchuria smuggled her Japanese birth certificate to her in prison during a visit. With proof of Japanese citizenship and not Chinese, the court ruled that she could not have committed treason and allowed her to “return” to Japan, a place where she had never actually lived. Ri Koran/Yamaguchi Yoshiko belonged to neither China nor Japan, but to Asia.

Her life and career occurred within the “Pop Pacific,” a shared transpacific cultural space where producers and record companies developed the musical ideas, technologies, and business strategies that made up the popular music industry in Asia. As a native speaker of both Chinese and Japanese, she could act and sing convincingly in both languages. She was also trained as an opera singer by a Russian who emigrated to Manchuria, further adding to her foreign appeal. The Manchurian Film Corporation, Man’ei, supported by the Japanese government, employed her to make films as their Chinese protagonist who agonizes over Japan’s invasion of China, but eventually recognizes the Japanese as benevolent masters committed only to helping China to modernize and improve the lives of its people. Yamaguchi claimed that her contract with Man’ei required her to keep quiet about her Japanese identity. She felt discomfort with this situation, but never publicly revealed her status or nationality until after the war. Having only known China as her home from birth to early adulthood, her arrest for treason and repatriation to Japan emotionally pained her.

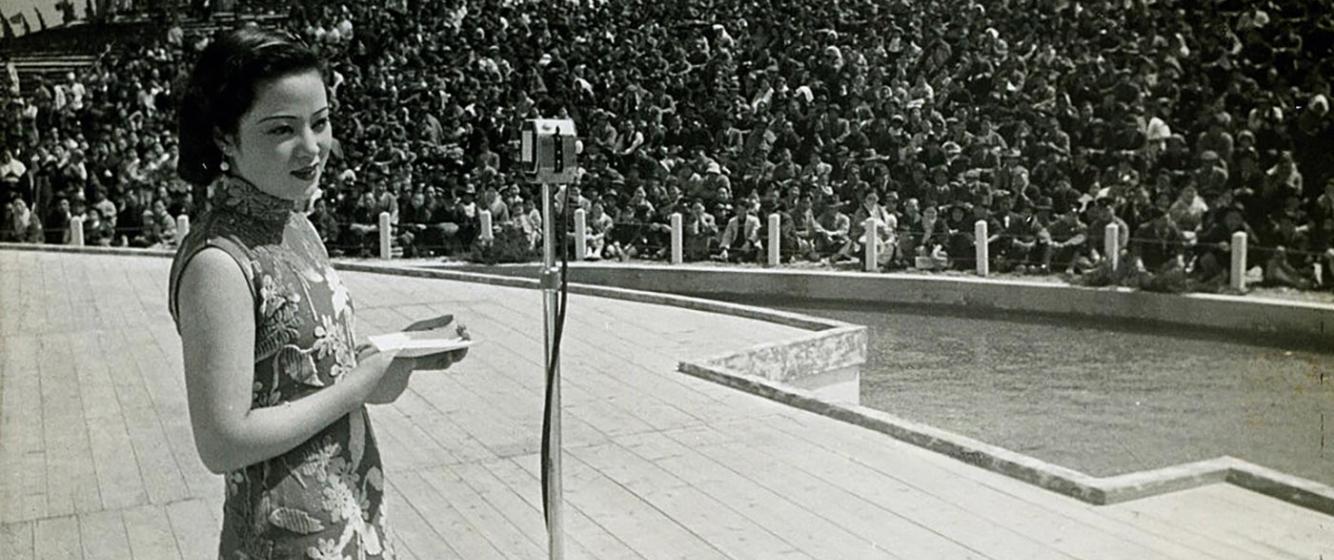

Other performers also shared Yamaguchi’s transnational confusion. Choi Seung-Hee, a young Korean woman impressed with a dance performance by Ishii Baku, one of the architects of Japanese modern dance, moved to Japan to study with him. Ishii encouraged her to develop her own style, and this seems to have included the inspiration taken from traditional Korean dance. She became Sai Shoki in Japan (the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters in her Korean name), and rose to fame as a modern dancer, also by mixing and showcasing an increasing amount of Korean traditional dance styles. Like Yamaguchi, Choi possessed great beauty. She had large eyes that seemed to hold her audience in their seats, an oval face with soft features, and an infectious smile. Her dance skills showed the long hours of practice and her commitment to her art. Her status as a Korean in Tokyo instantaneously made her both a colonial subject and an exotic celebrity. Perhaps she gained benefit from a Japanese trend in anthropology and ethnomusicology that saw Korea as a part of the Japanese empire in danger of losing precious indigenous traditions.

Interest in Choi and her choreography was high. As a model, she appeared in advertisements for beauty products, among others. As a modern dancer, her career was limited to Japan and Korea. As a representative of Korean traditional dance, and even as a magnet for supporters of Korean independence from Japanese colonialism, she became an international celebrity and even toured the United States. Choi, like Yamaguchi, eventually returned to Korea. After World War II, she moved to North Korea, perhaps to prove her loyalty to her Korean origins, and to escape the abuse she received in South Korea as a “collaborator” during the period of Japanese rule. North Korea was, in the early postwar period, both wealthier, and more interested in cultural preservation and international celebrity than South Korea. Choi eventually disappeared from public view in North Korea and her fate remains unknown.

Alice Fumiko Kawabata (Kawabata Fumiko), the last member of our trio of transpacific travelers, was a Japanese-American dancer in New York City who performed on Broadway. Born in the early decades of the 20th century, Kawabata found herself living in a society that saw Asians as unassimilable. In the 1920s, despite her great dancing skills, she was unable to gain access to major parts of the American theater. By facing this glass ceiling in the United States, and despite her inability to speak any Japanese (it was common practice for Asian immigrants to the United States to refuse to teach their American-born children their own native languages, in order to help them assimilate) Kawabata moved to Japan. In 1930’s Tokyo, she became one of Japan’s most popular jazz singer. Besides her physical beauty, Kawabata Fumiko became known in Japan for her American attitude, and for her accent when she spoke and sang in Japanese. Her Japanese audience recognized her American nationality, which gave her authenticity. This authenticity was bolstered by her thick, American accent and fluent pronunciation of English words, which differentiated her from other Japanese jazz singers. Due to her success in Japan, and lack of success in the United States, Kawabata eventually dropped her American first name, simply becoming Kawabata Fumiko.

The threads that tie these three artists together, apart from the usual celebrity recipe items of good looks, an outsized personality, and opportunity, are related to their transnational, trans-cultural experiences. Each of them gained recognition in a context unrelated to their culture of birth. Each learned to meld their adopted culture and host country with their birth culture, adopting multilingualism in order to mold themselves into pop stars with credibility. This manipulation of the audience’s desire for novelty and for authenticity came from the public’s own want and need for escapism. Popular music, as a business, treats music stars as products marketed to fans to sell records. In the pre-war Pacific, fans of Li Xianglan wanted an authentic Chinese beauty to sing the songs they loved, fans of Choi Seung-Hee wanted a gorgeous and original Korean dancer to show them their romantic idea of Korean tradition. Lastly, fans of Kawabata Fumiko were looking for a ravishing American jazz singer who could pass as Japanese. These three women and the industry constructing their fame gave the fans what they wanted, forging transnational celebrities in the process.

In my next post, I will examine the transnational nature of the musical world in which these three, and many more celebrities developed their styles and stardom.

Comments

Yamaguchi Yoshiko

There is no such place as "the Pop Pacific". It does not exist except in the author's mind.

If you want a full summary of Yoshiko Yamaguchi's life, look up the yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com website.

Add new comment