I am sad that I had to try to feed 400 migrant workers in Macau

The following narrative was constructed by Isabelle Cockel, based on two interviews that she conducted with Yosa Yanti, Chair of the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union (IMWU) in Macau. The first interview was conducted on 29 August 2021, and the second interview was conducted on 2 September 2022.

Arriving in Macau on a tourist visa

I am an Indonesian domestic worker in Macau. There is no agreement on the recruitment of migrant workers between Macau and Indonesia, so I came to Macau on a tourist visa. However, migrant workers like myself cannot be employed with this visa. From outside Macau, we know very little about how to find a job or apply for visas and work permits, so we have to use an agency to find an employer. The agency and employer will then apply for our work permit. Agencies charge us a lot of money, usually between $14,000 and $15,000.[1] If it is a job in the formal sector, then we often have to pay the agency a fee of double our salary, which is later deducted from our pay. Some people lose their jobs after one month but still they have to pay full fee to the agency. Paying such a large amount in fees and having our salary deducted is our biggest worry.

Before coming to Macau, I worked in Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong. In total, I have been away from home and worked abroad for sixteen years. I did not think much about it when I first started working in Taiwan. I was very young at that time. When I was working in Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong, I did not know anything about community work. When I was in Hong Kong, I worked with a very difficult employer so I took part in cultural activities, such as dancing, as a way to relax away from my very stressful work. I moved from Hong Kong to Macau after the old patient I was looking after in Hong Kong passed away.

Now in Macau I am a ‘live-out’ domestic worker. I rent a flat and do not live in my employer’s home. Some employers prefer to hire live-in domestic workers if they can provide accommodation for the worker in their home; others prefer to hire live-out workers if they do not have space for the worker. Some employers do this because they prefer to have their privacy and only need domestic workers to come to clean their home. There are pros and cons for workers, too. If living with their employers, they have less freedom, but they don’t need to pay rent. If they live out, they are free, but they have to bear the cost of accommodation, a challenge that has grown during the pandemic.

The daily working hours limit set by the Macau government for migrant domestic workers is 12 hours, and 8–9 hours for migrant workers in a hotel, casino, spa, or other businesses in the formal sector. The government’s justification is that we domestic workers can manage our time during the day, including taking a rest when we are not working, so our working hours are longer. In reality, we don’t always have time to take a rest. We have to stand by all the time.

My home was my office

My organisation, the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union (IMWU) in Macau, started helping migrant workers fourteen years ago, in 2008. We helped migrant workers who lost jobs, who encountered problems with their employers, or who did not know about their rights under labour laws. They could stay in our shelter and there have been many people staying here. In the past, on average, there were always four or five people staying in our shelter. We did not only help Indonesian workers. Those from the Philippines, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and other countries also came to us for legal advice on disputes with their employers or agencies. IMWU is not registered and has no licence to run our community work, but I have been able to connect with some local people and local associations who can help us when needed.

My two-bedroom flat is multi-purpose. To keep my head above water, I let out one room and I put a bunk bed in the other room for myself and everything else: it was the IMWU office, shelter and classroom where we offered language and computer classes for people employed in a range of different sectors. The language training we offered included Cantonese, English, and Mandarin because Macau is an international tourist destination. Local employers and businesses in Macau use Cantonese. English is less useful in everyday life, since the official language here is Portuguese, but international tourists speak English. Additionally, Mandarin is useful for dealing with tourists from China. Because of this mixed use of languages in our daily life, migrant workers in Macau need to know all of these languages.

We were very tired during the pandemic

In 2020, during the pandemic, many migrant workers lost their jobs because their employers were also out of work. We domestic workers were luckier because we could stay employed. Those who worked in the formal sector, such as in hotels or spas, became unemployed, due to forced closure. Some companies withdrew their sponsorship for migrants’ work permits; this withdrawal cut short the validity of their visas.

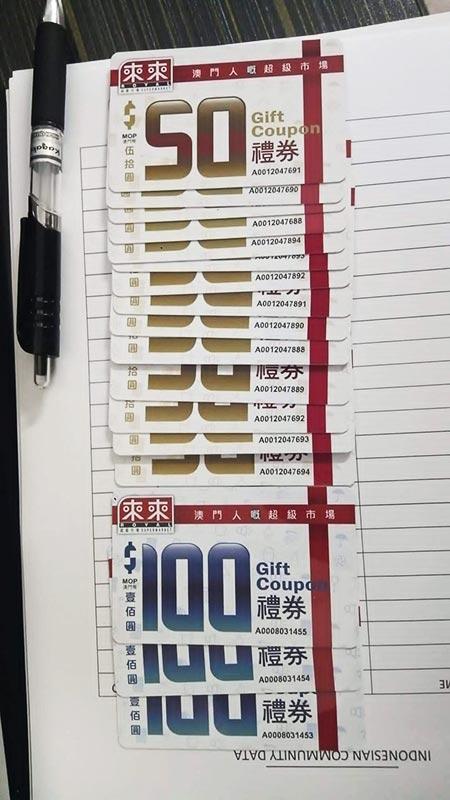

Packing donations

Dividing donations

The pandemic of 2020–2021 hit migrant workers really hard. Some did not have any income for four months; others were out of work for a whole year. Those who lost their jobs had to make the decision as to whether to stay or return home. If they stayed, they had no income when the cost of living here is very high. Moreover, they still had to pay rent. Some Indonesian workers managed to return home, when flights were still available and when the Indonesian Consulate was registering those who wished to return home. There were more than 5,600 Indonesian workers in Macau in 2020 before the pandemic, but 2,000 had left by August 2021. 8,000 Filipino workers had also left. Those from Vietnam were very unlucky. There were no flights available between Macau and Vietnam. They were stuck here.

Although I am a live-out domestic worker, my employer asked me to stay with them during the two-week lockdown in February 2020. They could not go out but they asked me to stay in their home. Some domestic workers came to seek advice from us during the lockdown. They refused to stay at their employers’ home during the lockdown, but their employers threatened them with the withdrawal of their work permit. Without it, domestic workers would not be allowed to stay in Macau. Only workers employed by businesses are employed with a standard contract; domestic workers are not, so their employment and residency in Macau are not secured.

Staying at our employers’ homes meant more work: more cleaning, more cooking and we also had to go out shopping. Everyone bought so much food! It was scary since people were not allowed to go out; the police would question anyone who was on the street. After the end of the two-week lockdown, we could go out and we had to wear facemasks. During the first wave of infection (January and February 2020), people in Macau panicked when there was a shortage of facemasks. They were sold at $8 for a pack of 10 masks. Macau residents, with their ID cards (locally known as ‘White Cards’), and Blue Card holders (foreign workers who are granted a work permit) were permitted to buy facemasks. But migrant workers who were on a tourist visa or those who were waiting for their visa found it very difficult to purchase facemasks; availability improved for them later on.

During the two-month lockdown in February and March 2020, I started to call for donations to help those who were out of work. I received donations from Indonesian people in Indonesia, Macau, and Hong Kong. They donated facemasks because, at that time, that was what we needed most. However, towards the end of March, we began to organise fundraising and use donated money to buy food. Local organisations and churches also gave us donations. It is very touching that they reached out and helped us. In 2021, there was another two-week lockdown between the fourth and eighteenth of August. One local organisation gave us rice, noodles, biscuits, and other things.

Supermarket shopping coupons

For one year, using Facebook, I organised fundraisings and gave food to people who came to my shelter. I created a group on Facebook and I shared information there. I collected donated money and a variety of things. I packed them into individual bags, as many as 200. I made a list of people who needed these bags and told people that they could receive these bags from me. I worked with our members after we finished our paid work. We domestic workers often finished work around nine and ten o’clock. Since we did not live with our employers, we started working on these donations after we went home. For me, I finished work at midnight and I often carried on working on arranging donations till three in the morning. Most Indonesian workers in Macau are women and so were my members. Luckily, six of my members are men; and more men joined to help us because they were out of jobs. They were very helpful for packing food, particularly dealing with those heavy rice sacks! At IMWU, we were all very tired but we were very proud that we could help others. We were also very happy that local organisations helped us at a time when it has been very difficult for everyone.

Closing down my office when the pandemic lingered

The latest lockdown between 20 June and 2 August 2022 hurt us badly again. How it happened still felt like a great chaos.

On the evening of June nineteenth, I had just finished work but my employer asked me to buy more food because there were confirmed cases in our building. At the supermarket, a local friend texted me about my parish being declared a ‘red zone’ (where there were confirmed cases of Coronavirus infection and, thus, earmarked for lockdown) and this was going to take effect the next day. After I returned to my flat, my phone did not stop ringing or beeping during the whole night. I answered all of them until six o’clock the next morning, and decided to run a livestream on my Facebook, explaining to my members what was happening. I also put up a map on my Facebook, but still people did not understand. The Macau government issued their orders in Chinese and Portuguese, but no information was given in English. When local media interviewed me about this, I told them that some people helped us by putting these texts through Google Translate and translating them from Chinese or Portuguese to Indonesian, but I had to check the translation since Google Translate did not always get it right. These new regulations took effect at midnight, which always made it difficult for us to respond and look after our members.

Another difficulty for migrant workers was border closures between China and Macau. If a worker has to renew their residency based on an extended contract, they can do it in Macau without leaving the territory. For those who get a new contract, they have to leave and re-enter Macau to get a new visa and work permit. Workers usually do this by getting a visa in Zhuhai. However, when the border was closed, they could not leave for Zhuhai so they could not start this employment process.

Out of 2,500 IMWU members, 400 people told me during this latest lockdown that they needed help, but I could not help so many. Sring Sringatin, the Chair of IMWU in Hong Kong, was in Jakarta at that time. She went to meet the Indonesian government and explained the situation to them. She also sent us rapid test kits from Hong Kong, because we needed a lot of them here in Macau. I requested a meeting with the Indonesian Consulate at their shelter and asked them to provide Vitamin C and shelter. They told me that they didn’t have money to buy food for Indonesian people and they could not accommodate them because they also had to abide by the rules in their parish, which set a maximum number of people staying in a public place. They told me the only thing they could do was to purchase flights for people who wished to go home. But they stressed that only poor people qualified for this fund. However, proof of qualification had to be provided by the government leaders in the person’s village, who gave evidence that this person and his/her family were poor. The problem is, people back home did not think those who worked abroad and their family were poor. They thought we were paid millions of rupiahs abroad, so how could we be poor?!

Campaign

In addition to the lockdown, we continued to withstand the worst of the lingering impact of the pandemic. In 2020, I was able to raise funds by posting on Facebook. At that time, local people could help because they were in employment, but this time around they were also out of work. I had to use my own money to buy food for distribution. With very limited money, we bought Indomie (Indonesian instant noodles), rice, tinned food such as sardines, bread, and more. We gave each person a pack of food, including two packs of Indomie, one tin of sardines, a loaf of bread and some rice. Each package cost $35. Some people told me that this was to be shared by four hungry people.

We distributed food in our office, at supermarkets or by an ATM machine. I told people to come to our office at a specific time, so there would not be a crowd gathered at our building. We worked together with another Indonesian group who packed food parcels and distributed them in their office. When distributing food on the street, we were usually in a group of five, we would be questioned by the police if the group was too large. I asked my local friends to deliver food to 30 people in far-away areas; they went by their scooter or van. We also collected supermarket gift coupons and gave them away so people could buy food. Some people donated coupons at a face value of $100, but I told them we needed those of a lower value, such as $50, so that we could give coupons to more people. We also used these coupons to buy food.

Very sadly, I have closed down my flat as IMWU office because I had run out of money. The flat cost me $6,500. I have to send home $1,000, keep another $1,000 for my own expenses and set aside roughly $2,000 to cover the costs of water, electricity and the Internet. I put another bunk bed in the multi-purpose room to increase its accommodation capacity but fewer people would be willing to pay to stay there because it was constantly noisy and busy, particularly as we had activities every Sunday. No one was renting the spare bedroom, so I was short by $3,500 every month, which I had to make up out of my own salary. After a difficult meeting with IMWU in Hong Kong, we made the painful decision to close down my office. Nevertheless, I am still thinking about how to raise funds to continue our community work because migrant workers need our help.

Life is still very difficult. I have to think about how to support my family and children in Indonesia. The pandemic may seem to be over for some but for me and migrant workers in Macau, it is not.

[1] All references to currency in this interview are to the Macanese pataca, or MOP ($).

Add new comment