She blows the whistle whenever she sees injustice

The following narrative was constructed by Isabelle Cockel, based on an interview that she conducted with Tsai Shun-jou, Director of the Hao Hao Women’s Rights Development Association based in Pingtung, Taiwan.

Her name in Chinese means tamed, obedient, malleable, or soft. Anyone who knows her would probably agree that she is anything but. She is a wonder woman of sharp views, witty expressions, abundant energy, a dry sense of humour, and infectious enthusiasm for causes she thinks worth a fight.

Shun-jou runs the Hao Hao Women’s Rights Development Association, a non-profit organisation in Pingtung at the southern tip of Taiwan, but she does more than empowering women, be they local, national, or foreign. She protested against the lower hourly payment for Southeast Asian language teachers, who are mostly female migrant spouses from Southeast Asia, when they taught optional modules of Southeast Asian languages at school.[1] Along with a group of mixed-ethnicity children born to Southeast Asian mothers, who were demonstrating on the street, she supported their demand for retaining the representation of Southeast Asian migrant spouses on the Management Board of the New Resident Development Fund and more diversified uses of this fund. This was to ensure that they would have a larger say in polices that affect migrant spouses and their children. In the early 2000s, mixed-ethnicity children were confronted with similar slurs when some officials and scholars described these children as slow developers or under-achievers. The New Southbound Policy, the flagship policy of the Taiwanese government, initiated some policies and may have converted the discriminatory discourse about mixed-ethnicity children as a liability to Taiwan’s international development into one claiming them as an asset for Taiwan. It is hoped that somehow, these children can deepen Taiwan’s relationship with Southeast Asia. However, such celebratory rhetoric has not effectively changed the popular mindset; it takes time to make meaningful changes.

She organised an international market on weekends, where foreign residents from around the world who have adopted Pingtung, this southernmost county, as their home sell their home-cooked food, handicrafts, or fresh produce. Some of them chose to perform traditional dance or music at the market; on such occasions, she encouraged children of mixed ethnicities to join in and perform with confidence in public. She runs a farmer’s training course where inexperienced farmers, including Southeast Asian wives, meet experts in specific crops and learn skills relating to fertilisation, pesticides and harvesting. She supported emerging talented documentary makers to film Southeast Asian women who, as local citizens’ spouses, found their new livelihood in farming after migrating to Taiwan.[2] She hoped that these films would raise public awareness of the poverty encountered by these farmers. When one of them could not look after her pineapple farm after her husband’s car accident, Shun-jou organised a ‘pick your own pineapple’ activity for the farmer to save her expensive crop from rotting in the field.

Isabelle Cockel is Senior Lecturer in East Asian and International Development Studies at the School of Area Studies, History, Politics and Literature of the University of Portsmouth. Her research focuses on labour and marriage migration in East Asia. Her recent research interests are the Cold War in East Asia, specifically the use of women’s voices for propaganda broadcasting.

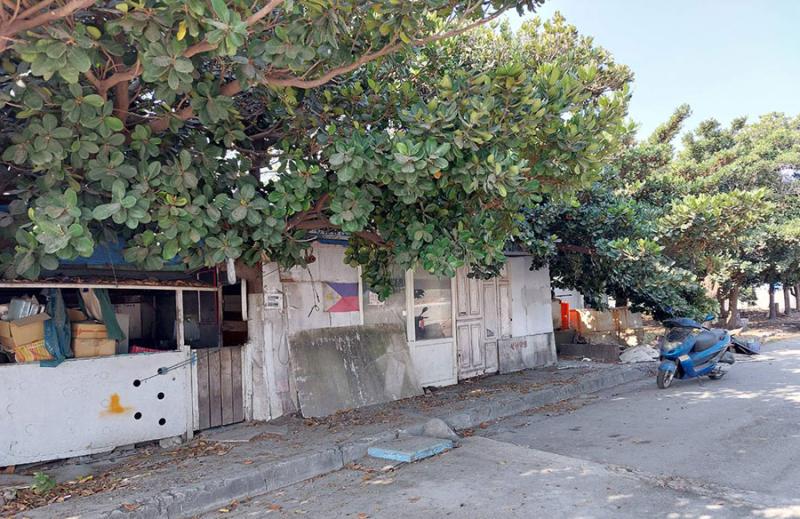

During the pandemic, what caught her attention was not only the slump in fruit prices but also the treatment of Indonesian fishermen who docked at the ports of Pingtung County. Pingtung is famed for the vibrant seafood market with its blue fin tuna, sakura shrimps and other costly catches. Indonesian fishermen returning from their months-long operations on the high seas came ashore at Yanpu and Donggang, two deepwater ports in Pingtung. They needed a place to rest. Most of all, they needed a shower and fresh water. However, in Yanpu, where they anchored, such facilities were in short supply. In 2014, opposite the port, they improvised, using whatever material was available to them, and built makeshift shelters in front of a thick row of tall rubber trees. Here, used as the headquarters of Kampoa Post, an Indonesian fishermen’s organisation, they could have a roof over their heads for rest, cooking, and to enjoy each other’s company. Some disused containers were reserved for their prayer room. They drilled the ground and used a pump to fetch fresh water. They showered in the open by pumping the underground water. This had not been a concern until the pandemic arrived and face covering in open spaces became compulsory. Indonesian fishermen were caught and fined by the Kaohsiung government for not wearing facemasks while showering.

One such incident caught her attention. In 2020, during an inspection of foreign fishermen’s living quarters at Kaohsiung Port, she took pictures as evidence showing that foreign fishermen were not able to use the two shower rooms (disused containers refurbished for this purpose) built by the government because they were locked. In Yanpu Port, although the same kind of facilities were not locked, there were only five such shower rooms for 4,000 foreign fishermen working on Taiwanese-owned or foreign-flagged vessels. She contacted the government about the lack of facilities, which affected the fishermen’s wellbeing, but she was told that off-duty fishermen could sleep on their vessels.

‘Would you sleep in your workplace after you had worked there for months?’ She did not accept ‘sleep on the vessel’ for an answer, partly because of the crowdedness of the sleeping quarters, where one has a space just 90 centimetres wide and 150 centimetres long to sleep.

A follow-up answer from the government was ‘if they have nowhere to go, they can stay in a hotel’ and ‘this is not the government’s responsibility’.

As an activist familiar with human rights issues in a busy fishing county, Shun-jou was all too aware of how the mistreatment of foreign fishermen in Taiwan’s deep-sea fishing industry has been under the international spotlight. She submitted her petition to the Control Yuan, demanding a public inquiry into how foreign fishermen managed daily life in their locality, why there was no provision of shower rooms and fresh water for them, and the consequence of forcing them to deal with their basic needs in public.

The inquiry into the government’s wrongdoing was held and she was invited to attend meetings with government officials, vessel owners, and fishing industry representatives. Arriving with her immigrant staff and attired in clothing of ethnic style, she was mistaken for a Southeast Asian spouse. One official began the meeting by saying to her ‘You migrant women “hang out together” with migrant workers, you should watch out for yourself.’

‘Hang out together’ in this context in the Taiwanese language means having a sexual relationship. Shou-jou could not take such an insult and protested against such outright humiliation.

The public inquiry into facilities for Indonesian fishermen seemed to have come to a positive end. A Fishermen’s Leisure Centre is going to be built in Yanpu Port. Much funding committed by the central government is going to be spent on the port’s renovation not only for the fishing industry but also for enhancement of tourism, with the planned Leisure Centre to be built in the port. Whilst making noise seemed to have paid off, Shun-jou was surprised to be repeatedly told by the government that ‘it’s better to let the leisure centre be used only by Taiwanese fishermen.’ She challenged this decision:

-‘Why can’t Indonesian fishermen use it?’

-‘Well, you know, it doesn’t look nice.’

What the government means by ‘doesn’t look nice’ is that they are worried that Taiwanese tourists may be put off by the sight of Indonesian fishermen. Her response was: ‘Can’t you see that it is Indonesian fishermen catching the seafood sold in this market?’ After several press releases, a compromise was found whereby a separate leisure centre for foreign fishermen will be built in the logistics yard of the port.

In Shun-jou’s eyes, this blindness to the fact that migrant workers are human beings, rather than a mere source of labour purchased only for their productivity, devalues humanity. Being vigilant about the prevalence of discrimination and resisting the indifference to the existence of discrimination is the very first step towards the improvement of human rights for men and women, be they citizens or migrant workers.

[1] https://www.storm.mg/localarticle/4473186.

[2] See the interview with Wu Che-wei in this special issue.

Add new comment