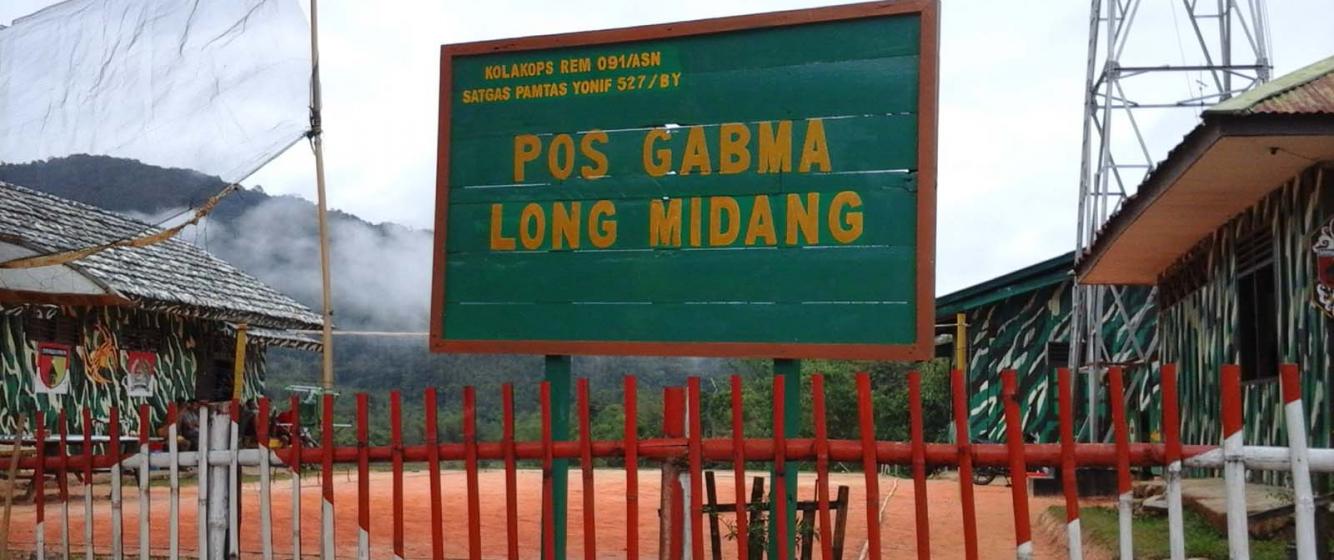

Fig 1. Military border check point in Long Midang (Indonesia)

One State, six borders: the multifaceted borders in Krayan region, Indonesia

When I carried out fieldwork in the Kalimantan border areas straddling Indonesia and Malaysia, I asked my interlocutors about their perceptions of the border and their border crossing activities. I imagined this to be a straightforward question for members of the borderland communities. To my surprise, many sought clarifications on what kinds of border I was referring to. This was when I realised that multiple and often overlapping boundaries were a feature of everyday life for the local Krayan communities. How, then, are multiple forms of boundary and boundary-making experienced and perceived by the Krayan borderland communities?

Over the course of my research, I have documented six forms of borders in Krayan that are overlapping and entwined with Indonesia’s national development agenda. The (re)creation of different forms of borders has been instrumental in Krayan from a local perspective as part of the larger state project of development implementation.

The state border manifests itself through flags, border monuments, a military line of defence, and the immigration posts. The state border coincides with the National Park zonation. In the 1980s, Krayan was known to be part of the Kayan Mentarang Nature Reserve, which subsequently became a National Park in 1996 for better natural resource management and to boost economic development. Although this happened more than 20 years ago, local villagers remembered this change and gave it special significance. The National Park zoning by the state implied the delimitation of Krayan as an area for future economic development.

On top of the state and park borders, the village administrative borders mean something different to the local people as well. Prior to the 1970s a village in Krayan was known as a kampong, consisting of ten or more communal households living together in one traditional longhouse (Rumah Panjang) situated within the dense tropical rainforest. Following the central government’s recommendation at the time, members of these communal households split up and each household had to move into separate dwellings located in more accessible areas. This change was deemed beneficial in terms of bringing the locals closer to basic amenities such as transportation, schools, and medical facilities available in the new administrative villages. There are currently 89 new administrative villages in Krayan.

The term ‘location’ is also used by Krayan locals with reference to borders. Also known as lokasi or klaster, a ‘location’ refers to the government designated strategic dwelling places to which new villages have been relocated. A location is deemed strategic when it has an airstrip, a crucial asset in Krayan because the region is only accessible via light aircrafts.

Fig 2. The immigration post in Long Midang (Indonesia)

In terms of ethnic boundaries, the ethnic group Dayak Lundayeh forms the majority of Krayan region local population. ‘Lundayeh’ are communities living in the Borneo Highlands, a name given by their lowland neighbours. The main subdivisions of the Lundayeh in the region are the lun tanah lun, lun nan ba’, and leng ilu’. Other Dayak ethnic groups sharing the same region are the Sa’ Ben and Punan. The ethnic subdivision of the Lundayeh is relevant in capturing the border in two ways – 1) borders emphasize the persistence of distinctive group identities; and 2) borders foster diversity within Lundayeh rather than treating it as a homogenous, pre-defined community.

Lastly, the cultural border of Krayan is also reflected through religious denominations. Most Krayan locals embrace Christianity, and as a result different church affiliations serve as a distinguishing marker that separates different villages. There are three main church denominations in the region including the GKII (Indonesian Tabernacle of Gospel Church), the GKPI (Christian Church of Light of the Gospel) and the GBI (Indonesian Bethany Church), which are instrumental in creating additional social and religious borders by emphasizing distinctive group identities. Such divisions serve important local social functions – 1) it promotes a parallel bordering process that consolidates ethnic divisions alongside church divisions; 2) it promotes the continuity of bordering as a process beyond the dominant ethnic identification; 3) it illustrates how social boundaries coincide with the territorial border.

One State, six borders, by Krayan local perspective, offer insights on how development energises, if not catalyse, the boundary making in the locals’ everyday life. Their forms are integral yet separable. Bordering is an intrinsic part of state-making in terms of economic and social development through park zoning, new village relocation and administration. It also shows the dynamic interplay of local ethnic identification and differentiated religious affiliations.

Add new comment