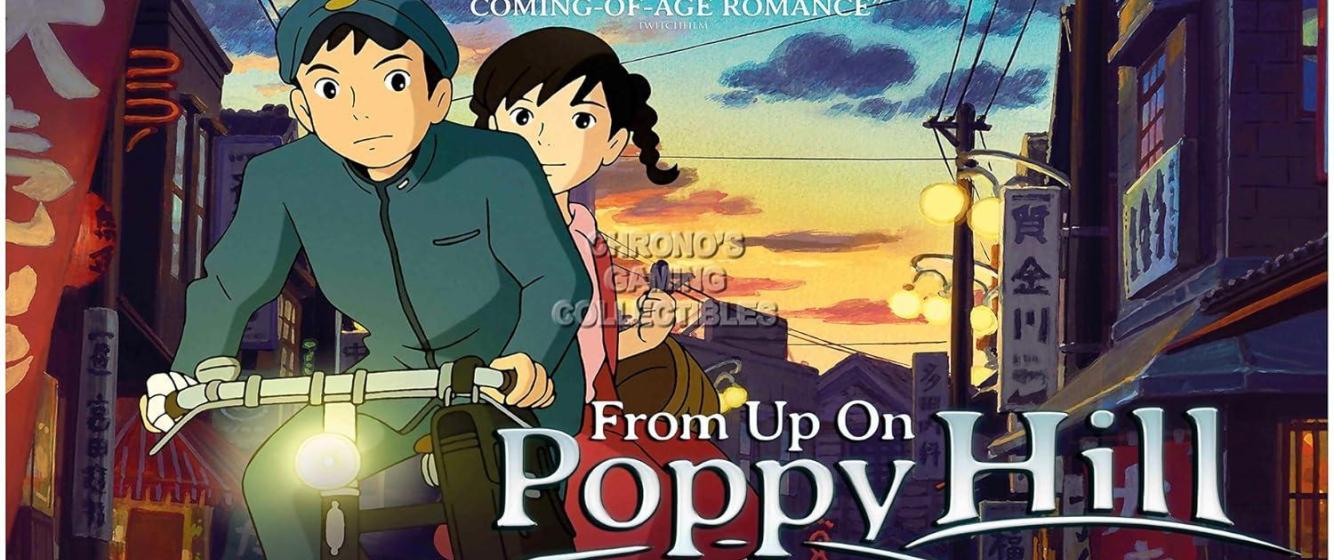

Young Love, 1963: From up on Poppy Hill (2011)

Studio Ghibli's From Up on Poppy Hill is a stylistic gem, delivering postwar teen angst, Yokohama-style

Unless you've been the subject of a self-imposed entertainment blackout (I was about to say "living under a rock," but isn't just about everyone in this heinous age of virtual interaction?), you probably have some passing familiarity with the animated films of Studio Ghibli. One of their productions, Spirited Away, made the top ten of a recent New York Times list of "The Best Films of the 21st Century," alongside the work of the likes of David Lynch and the Coen Brothers. An animated film. A cartoon. If you've been reading my posts, you know that I love mid-century (or mid-century themed) pop culture, and I love cartoons. My favorite Studio Ghibli offering is both.

I know, I know—most self-proclaimed Ghibli aficionados will say that Spirited Away, or the pastorally innocent My Neighbor Totoro, or the epic fable that is Princess Mononoke deserve the honor of "best" Studio Ghibli production. Here in Honolulu, where we have a yearly Ghibli "festival" every summer at the Kahala Theatres, those three films play every year, while most of the others are rotated and make an appearance every other summer or once every three years. And I don't disagree. Critically, I'd probably place those three at or near the top. I love all of Ghibli's offerings, and it's no exaggeration to say they're all good: even the "worst" Ghibli movie beats the shit out of the "best" Disney animation offering in the contemporary period. Even Disney acknowledged this by acquiring the international distribution rights to Ghibli in 1996, which it mostly held until 2017. My favorite Ghibli film, though, is the comparatively unheralded From Up on Poppy Hill (2011).

Poppy Hill is, in fact, probably one of the most reviled and disparaged projects in the Ghibli oeuvre, owing more to the fact that its director, Goro Miyazaki, has been the target of criticism than to any opinion that it's a bad movie. Goro Miyazaki is the son of legendary anime director Hayao Miyazaki, the genius behind most of Ghibli's acclaimed gems. Goro's first offering, Tales from Earthsea (2006), based on the works of Ursula K. Le Guin, was largely panned by critics and called by some Ghibli's "worst" movie. Ghibli fans vilified Goro, accusing him of the sin of failing to live up to his father's legacy. Earthsea was visually stunning and not bad at all. But when compared to the rest of the pantheon, it admittedly doesn't stand up. Perhaps Earthsea's most detrimental effect was that it caused critics and fans to dismiss Poppy Hill.

Poppy Hill isn't like the rest of Ghibli's catalogue in that it lacks an element of the fantastical. This alone probably causes most Ghibli fans to reject it. There is no magic, no time travel, no made-up world, no supernatural phenomena. There isn't a single talking animal. It's the story of a girl and a boy and how a past they didn't choose complicates their desire for each other, set against the backdrop of a Japan in transition, recovering from the devastation of war and emerging as a future global economic power. The Japan of Poppy Hill is moving toward that status by leaps and bounds, as illustrated by its setting: Yokohama in 1963, a year before the (first) Tokyo Olympics.

Sounds pedestrian, doesn't it?

What it lacks in fantasy pyrotechnics, Poppy Hill more than makes up for in gorgeous period detail and superior directing by Miyazaki. The younger Miyazaki. Goro. The whipping boy of the Ghibli fan inquisition. That Miyazaki.

In his portrayal of first love, Goro bests his legendary father. My favorite scene has our leads, Umi, the ultra-competent heroine, and Shun, the cool school newspaper editor, pass each other on a residential street in the early evening when Umi is on her way to the butcher at the bottom of the hill. Shun hits the brakes as soon as he realizes it's Umi, and as he backs his bicycle up, Umi blushes. He notices the empty basket she carries and asks, "Going shopping?" He offers her a ride on his bike, which she accepts and hops on. The visuals and the music make you feel the pull toward each other. Umi is clad in a pink blouse with a skirt and cardigan. Shun sports his Prussian army-inspired school uniform. Their spare dialogue floats on Kyu Sakamoto's "Ue o Muite Aruko," an ebullient period tune better known in the West as "Sukiyaki."

Their palpable attraction to each other is in their expressions, subtle but unmistakable. The dying sunlight in the sky casts purple shadows on the street, and as Shun's bicycle nears the bottom of the hill, the neighborhood gives way to a bustling Yokohama shopping district illuminated by electric bulbs and storefronts and the headlamps of vehicles in the crowded street. All with Kyu Sakamoto crooning in the background. And while first love is still a condition that continues to afflict today's youth, it was suffered with more panache in 1963, or so this movie would make you believe.

Who says there's no magic in Poppy Hill?

.

There are period touches in Poppy Hill that are absolutely enchanting to a retrophile like me. There are the nerdy denizens of the old Meiji-era building on campus dubbed the Latin Quarter, an impromptu clubhouse for astronomy geeks, ham radio operators, amateur chemists, poets, a resident philosopher, and Shun's newspaper. Rugby and tennis players' uniforms still sport collars. Umi's house, owned by her grandmother, is home to female boarders, all of whom are clad in period outfits. My favorite is the buxom Saori Makimura, who wears a white blouse with a brooch at the collar, red lipstick, and has her hair in a semi-beehive. She looks like she's been cut out of the pages of the Japanese equivalent of Harper's Bazaar, circa 1963.

.

Saori Makimura (far right), Poppy Hill’s “It” Girl

Yokohama is a harbor town, and the port and vessels are illustrated with attention to mid-century maritime technology. The scenes are awash with period colors: red, green, and black hulls, worn wooden dockside edifices displaying signs graced with faded paint characters. The soundtrack by Satoshi Takebe is jazz-inspired, combining a West Coast Cool School bass line with a Nat "King" Cole-like piano and a Benny Goodman-like clarinet.

While the rest of Studio Ghibli's catalogue makes your jaw drop with the revelation of bright-hued fantasy worlds, Poppy Hill quietly makes you nostalgic for a time you never lived through and a place you never lived in.

That's the greatest trick of all.

_______________________________________

Scott Kikkawa is a fourth generation Japanese American raised in Hawai'i. Currently a federal law enforcement officer, the New York University alumnus is the author of three noir detective novels set in postwar Honolulu—Kona Winds (2019), Red Dirt (2021), and Char Siu (2023) and numerous other short stories. He can be contacted at scottkikkawa@gmail.com

Discussion Questions

- The author suggested that fans rejected Poppy Hill because it has “no magic” but the author says it's magical in its own way. What kind of magic is he referring to, and how is it different from fantasy or supernatural magic?

- Kikkawa argues that love in 1963 was experienced with more “panache.” (look up this word if you don’t know it) Do you agree or disagree? How might love today look different—and why?

- How does Poppy Hill reflect the social and historical changes Japan was undergoing in the early 1960s? Why might this be meaningful for a modern audience, especially outside Japan?

- The article highlights how fashion, music, and architecture all contribute to the film’s emotional impact. What are some elements from your own everyday life that might seem magical or nostalgic to someone in the future?

- The film creates nostalgia for a time and place many viewers never experienced. Why do you think films and music from the past have the power to evoke longing for eras we didn’t live through? Can this kind of nostalgia be both positive and problematic?

- The article mentions that director Goro Miyazaki was heavily criticized compared to his father Hayao Miyazaki. What challenges do children of famous or successful parents face when trying to make their own mark? Can you think of any other examples in film, music, or sports?

Add new comment