Beonangayo: How Korean Musicians Transformed Western Songs into the Foundation of K-pop

Before there was BTS, there were three sisters who shook America.

The year was 1964. While the Beatles were captivating American teens with their energetic Merseybeat songs, three young Korean women were making history on television. The Kim Sisters performed on The Ed Sullivan Show and became the first Korean act to appear on American television, confidently belting out popular hits.

The Kim Sisters featured in the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964, performing The Coasters' "Charlie Brown"

More than 60 years before BTS became a central figure in the global scene, before the world knew the terms 'Korean Wave' or 'K-pop,' these three sisters proved that Korean artists could master Western genres, captivate American audiences, and bridge cultural divides. They were among the first post-liberation artists to sing American-style songs. But their Western sounds were drawing upon a tradition of musical revolution that began long before anyone was paying attention through a transformative practice known as Beonangayo.

What is Beonangayo?

Beonangayo is a compound word formed from 'Beonan' and 'gayo.' The term Beonan refers to the act of translating or adapting foreign language content into Korean, while 'gayo' is a term referring to popular music in Korean. Thus, Beonangayo is a term used to describe foreign popular music rearranged by Korean musicians, with lyrics either translated, paraphrased, or even newly created in Korean. As for the English term, Beonangayo can be described as Translated Popular Music (TPM), which could include changes in lyrics and instrumentation.

Most TPM tended to follow the instrumentation of the original work, though exceptions existed due to differences in musical environments or artistic techniques. As for lyrics, direct translation was common at first. Over time, however, lyricists and composers began writing entirely original lyrics, which could be seen as a process of cultural indigenization. In an era largely unaware of international copyright standards, the government and the general public embraced TPM as a legitimate form of Korean popular music.

The Early Foundations (1920s - 1930s)

Public domain image

The first Korean soprano, Yun Sim-deok (1897-1924)

The history of TPM extends back to the early 20th century, to the earliest days of the Korean popular music industry. A pivotal moment occurred in 1926, with the release of Sa'ui Chan'mi (In Praise of Death), the first Korean popular music recording. This historical piece was arranged based on Joseph Ivanovich's waltz, Waves of the Danube (1880). Interestingly, the Danube was later rearranged as an American popular song "Anniversary Song" in 1946, featured in the musical film The Jolson Story. In that sense, Korean TPM predates the American version, making Sa'ui Chan'mi one of the earliest known cases of transforming classical or instrumental music into popular music.

Yun Simdeok’s Sa’ui Chan’mi (In Praise of Death, 1926), known as the first recorded form of Korean popular music.

During the Japanese colonial period, TPM flourished, particularly within the genre known as "Jazz song" (Jyaz Song). Despite its name, this genre extended beyond jazz and encompassed a wide range of Western popular music. Songs such as St. Louis Blues, Ave Maria, and Oh My Darling, Clementine were introduced in Korean society through TPM during the 1920s and 1930s.

During this period, it became clear that Beonangayo was not an exclusively Korean phenomenon. Western record companies such as Columbia, Okeh, and Victor had established branch offices in both Japan and Korea, facilitating domestic access to foreign music. Much like Korea, Japan also began releasing adapted forms of Western popular music from the early 20th century. Due to political and economic control of colonial Korea by Japan, TPM repertoires were often shared between Japan and Korea, with Korean versions mostly released after Japanese ones.

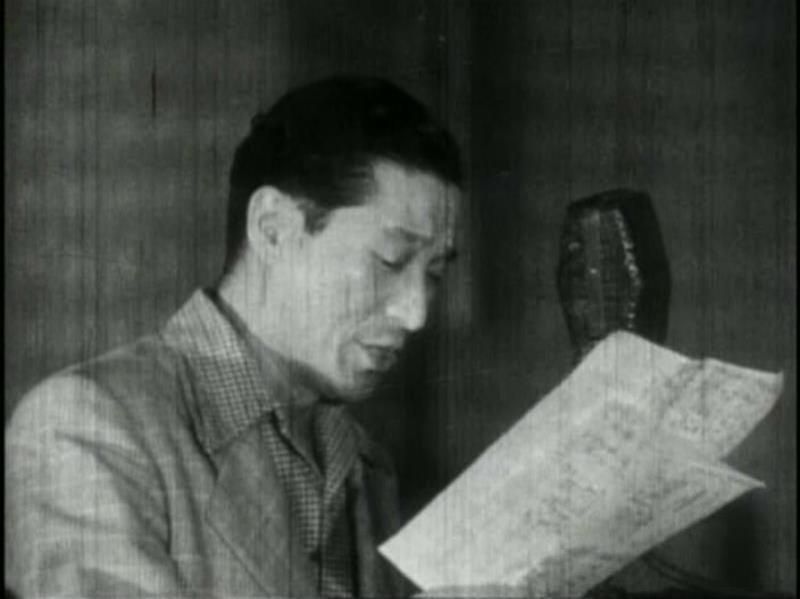

Public domain image

Singer Dick Mine in 1948

For example, Dinah, originally composed in 1925 and introduced as a major hit by Ethel Waters in 1926, and later recorded by Bing Crosby in 1931, was released in an adapted version in Japan in 1934, performed by Japanese singer Dick Mine (1908-1991).

Dick Mine’s “Dinah,” originally released in 1934, remastered in the album Empire of Jazz, 2011

Using a Korean name, Sam U-Yeol, Dick Mine recorded Dinah again in 1936 – this time in Korean.

Dinah released by Okeh Record Korea in 1936, artist : Sam U-Yeol (Dick Mine)

A similar case occurred with My Blue Heaven. Originally performed by Gene Austin in 1927, it was released in Japanese as Aoi Sora (Blue Sky) in 1928, and later as the Korean version Jeul’geo’un Na’ui Sal’lim(My Happy Housework) in 1935. Compared to the Korean version, the Japanese version is faster and features a group of backing vocals.

Japanese version of My Blue Heaven in 1928

Korean version of "My Blue Heaven" in 1935

Prior to the war until the late 1930s, when the Japanese Government-General banned music originating from the Allied countries - more than 400 Beonangayo works were produced in the industry. These songs played a role in shaping early 20th century Korean popular music.

Post-War Revival and the U.S. 8th Army Show (1950s - 1960s)

The Kim Sisters were the product of cultural mixing in post-war Korea, particularly in Itaewon through the U.S. 8th Army Show. Following the Korean War, the US 8th Army was relocated from Japan to Yongsan and the military entertainment show officially launched in 1955, to entertain the troops. Many Korean artists were performing on the stage under Americanized nicknames such as the Pearl Sisters, Johnny Brothers, Jacky Shin (Shin Joong-hyun, the godfather of Korean rock), Benny Kim, and the famous Patti Kim.

Much like The Beatles, who started as a cover band, well-known Korean artists in the 1960s followed a similar path. The venue, which aimed to entertain the American soldiers, became the school for local performers to learn and perform new songs, like mambo, twist, swing, and rock and roll. It was a central ground for Korean musicians and musicians-to-be to educate themselves with the ways to perform the various types of popular music. At that time, the domestic popular music industry was still struggling with the aftermath of the war, and the U.S. 8th Army show provided a vital source of musical inspiration and employment. This was a kind of goldmine for what would later become the foundations of modern Korean popular music.

Western popular music, categorized by the name of 'Pop Songs' (pab song) in Korean society, began to flourish from this period. During the 1950s, the government implemented a Korean language-only policy in order to reconstruct the national identity after the Japanese forced assimilation policies of the colonial period that banned the use of Korean in schools during wartime. Foreign popular music was permitted only when performed in Korean. This linguistic restriction marked the revival point for Beonangayo. The Kim Sisters even sang Eddie Fisher's "I Need You Now" (1954) as TPM titled "Happy Saturday" (Julgeoun Toyoil), effortlessly switching between both Korean and English in a 1956 movie!

The Opening Scene of 1956 Korean Film Cheong'chun SSang'gok'seon (Hyperbolae of Youth), featuring the performance of "Happy Saturday" by the Kim Sisters. The guitar player, Park Si Chun, is a well-known pioneer of Korean popular music, and composed over 3,000 popular songs during the colonial period.

The Golden Age of Adaptation (1960s - 1980s)

One of the interesting aspects of TPM is that there was often little or no time gap between the release of the original song and its Korean adaptation. Thanks to AFKN (American Forces Korea Network), which operated beyond the reach of government censorship, this immediacy was possible. By transcribing melodic lines and chord progressions from AFKN shows, Korean artists could engage with genres such as rock, modern folk, canzone, chanson, and disco. These were genres that might never have appeared in Korean industry without such efforts.

In addition, due to the strict regulations on record production, including the importation and publication of the foreign records, TPM served as a major conduit for introducing new music from foreign countries, eventually diversifying the Korean popular music scene and providing new cultural experiences to the younger generation. Through the production of TPM, these new styles of popular music were rapidly localized and integrated into the Korean popular music industry from the 1960s through the 1980s.

A Scene from movie "C’est Si bon" (2015)

This clip is from a biographical film of the group ‘C’est Si bon’, widely known as a key figure in the 1970s Korean Folk Scene. This scene features the song ‘Wedding Cake’(1969) in the background. This was an adapted version of Connie Francis’ original ‘Wedding Cake’ (1969). This exemplifies TPM where lyrics differ entirely from the original while the melody and chord progression remain unchanged.

Although TPM had once dominated the popular music scene, TPM eventually faced the end of its heyday. Before the decline, over 1,000 TPM songs had been produced. In 1987, the United States and Republic of Korea concluded an agreement on Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs). Based on the agreement, the Korean government revised the copyright law, primarily with the intention of banning illegally copied foreign recordings or pirated copies. However, this revised law also included clauses that were detrimental to TPM production. The era of TPM ended, but its legacy continues to resonate within the Korean popular music industry.

The Legacy: From Imitation to Innovation

TPM exemplifies how popular music in the 20th century served as a cultural bridge between nations. Moreover, it reveals the potential possibilities of discovering other adapted forms of Western popular music across Asia beyond the Korean case of Beonangayo. Recent research has demonstrated that not only Japan and Korea but also Taiwan and Thailand have adapted Western music and performances in their own ways. Westernization in popular music can be understood not merely as a power dynamic but as a voluntary process of cultural localization.

Although TPM might be considered as a derivative work and a violation of copyright standards, it served as a motivational force that enabled the diversification of the Korean popular music industry from the early 20th century. As Aristotle once said, “Imitation is the mother of creation.” TPM can be seen as the mother of Korean popular music. By introducing novel sounds from abroad, TPM allowed Korean musicians to learn and adapt various styles, eventually giving birth to distinct domestic genres such as Korean folk, Korean rock , Korean dance music and Korean ballads. All of these genres constitute the mainstream of today’s Korean popular music industry.

TPM demonstrated how music could play a significant role in intercultural communication, and how musicians and artists could develop their own style through adaptation, evolving beyond the original. The trajectory from early Jyaz Song to Kim Sisters’ U.S. success, and finally to BTS and BLACKPINK’s worldwide popularity, reveals a long-standing tradition of embracing and internalizing foreign musical influences within the Korean popular music industry. Ultimately, Beonangayo was pivotal in forming the musical and cultural environment that led to the rise of K-pop in the 21st century.

___________________________________

PARK So Hyun is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Musicology at Seoul National University (SNU). She is currently working on her dissertation investigating 1990s Korean popular music. This post is drawn from her MA thesis, completed in 2021 at SNU, and the section covering the period after the 1960s is drawn from her upcoming work on adaptation of songs in Korean popular music. She can be reached at so7831@naver.com

Discussion questions

- What does "Beonangayo" mean, and what practice does it describe?

- The Kim Sisters sang songs on American TV in the 1960s. How do you think American audiences might have reacted to three Korean women performing familiar hits?

- Beonangayo often began as direct translations of Western songs but later developed new Korean lyrics and styles. At what point does an adaptation stop being a copy and become its own cultural creation?

- Why do you think some Korean audiences enjoyed translated versions of Western songs in the 1920s–1960s instead of only listening to Korean original songs?

- Can you name something in your country that started as a copy but became local and unique?

- What does Beonangayo tell us about how cultures share and change ideas?

- How does knowing Beonangayo help you understand global music like K-pop better?

Playlist (Listen before or during class)

Colonial-Era Adaptation (1930s) – Same Song, Different Versions (2 min). Show how one American song turned into different Japanese and Korean versions.

- Gene Austin – My Blue Heaven (1927, original clip) (30 sec)

- Japanese version – Aoi Sora (1928) (30 sec)

- Korean version – Jeul’geo’un Na’ui Sal’lim (My Happy Housework, 1935) (30 sec)

Postwar Success (1960s) – Korea Meets America (2 min)

- Eddie Fisher - “I Need You Now” on The Ed Sullivan Show (1954) (1 min)

- The Kim Sisters – “Happy Saturday (TPM version ofI Need You Now)” (1956) (1 min)

Add new comment