Large Eyes, Pointy Chins, Pointy Noses: How Manga Became "Manga"

.

Fig. 1 - French comic strip Rigobert from 1923

Outside of Japan, the word manga is used not only as a synonym for Japanese comics but often also to describe a particular drawing style associated with Japanese comics. This latter association is so strong that I have heard from more than one person teaching classes about manga that when they show their students Japanese comics that predate the 1960s, some will object, “That’s not manga!” What such students have in mind when they think “manga” becomes clear when you look at covers of books promising to teach “how to draw manga:” characters whose faces are marked by (1) pointy chins; (2) small, pointy noses slightly upturned; and (3) unrealistically large eyes.

Despite the strong association between manga and this facial pattern, writing on the pattern’s historical origins has been surprisingly scarce. One of my central motivations behind writing Manga: A New History of Japanese Comics was to pay due attention to characteristics of manga as a visual medium, and I assumed that the origins of “the manga face” would be one such characteristic of particular interest to most readers.

The initial development of the stereotypical manga face can be traced back to the work of the influential comics creator Osamu Tezuka, who began using a character design with a pointy nose for some of his juvenile protagonists around 1950. At that point, most Japanese comics protagonists still featured button or bulb noses (i.e., a closed or open circle or oval attached to the face). Eyes in manga were already larger-than-life across the board, a relic from early newspaper comic strips. There was little specifically Japanese about Tezuka’s pointy-nose character design, either; similar character designs could be found in some early comics abroad as well (see fig. 1).

But because of Tezuka’s popularity, pointy noses became more common over the course of the 1950s, especially in magazines for girls in the wake of Tezuka’s hugely successful romance and adventure comic Princess Knight, serialized in one of those magazines (fig. 2).

.

Fig. 2: Princess Knight by Osamu Tezuka

The specific facial design associated with manga nowadays emerged out of the work of two other artists: Macoto Takahashi and Tetsuya Chiba. Both Takahashi and Chiba were influenced by Tezuka’s comics, but their styles look recognizably more similar to mainstream manga of today than his. Macoto Takahashi was primarily an illustrator and appears to have come to comics largely because it was a booming industry with high demand for artists (and hence solid pay), rather than due to a strong interest on Takahashi’s part in comics as an art form. Takahashi was enamored of elegant illustrations of fashionable pretty girls. He treated every drawn page not just as one element of a story but as a work of art in its own right, as is evident from his practice of signing each individual page during the beginning stage of his career in the early 1950s.

.

Fig. 3: Character drawn by Macoto Takahashi

In stark contrast to most other manga artists, who used more cartoonish styles, Takahashi tried to make his girl characters look beautiful and elegant (fig. 3). One element of this more elegant look was the slender, pointy, slightly upturned nose so closely associated with manga today. Takahashi also kept the eyes large (while making them more elegant) and turned the chin into a pointy angle, creating the facial design that still dominates mainstream manga today. Macoto Takahashi’s style proved popular and was adopted by other artists drawing comic strips serialized in girls’ magazines in the late 1950s, contrasting starkly with more cartoonish styles still widespread at the time. Takahashi’s influence is obvious from his practice of frequently interrupting the nose line at the tip of the nose, which was quickly adopted by other artists drawing for girls’ magazines. During the 1950s, this style was largely confined to these, but would eventually influence the drawing styles used in boys’ magazines as well.

Children’s magazines were booming at the time and increasingly relying on comics as content, leading to demand for comics outpacing the supply, which attracted new creators. Because boys’ magazines were considered more prestigious (and almost certainly paid better), established creators primarily worked for those, forcing many new manga artists to start out drawing almost exclusively for girls’ magazines. Editors at magazines encouraged artists to imitate popular styles, and since Takahashi’s drawing style was popular, most artists who began their career at girls’ magazines in the late 1950s were influenced by this style to some extent.

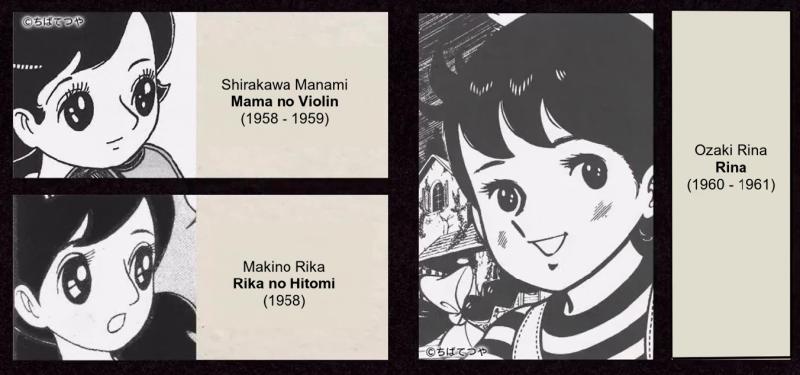

The most important of this cohort of new manga artists was Tetsuya Chiba. Chiba started out drawing comics for the monthly Shōjo Kurabu (Girls’ Club), published by the large magazine publisher Kodansha, which had begun using comic strips to help sell its magazines already in the 1920s. Over the course of three successive serials in Shōjo Kurabu, from 1958 to 1961, Tetsuya Chiba started drawing the noses of his protagonists noticeably more pointed and upturned, similar to Macoto Takahashi’s style (fig. 4).

.

Fig. 4: Evolution of Tetsuya Chiba’s Style from 1958 - 1961.

In 1959, the publishers Shōgakukan and Kōdansha founded Japan’s first weekly kids’ magazines, Shūkan Shōnen Sande and Shūkan Shōnen Magajin (“Weekly Boys’ Sunday” and “Weekly Boys’ Magazine,” often simply referred to as Sunday and Magazine). Initially, Kodansha’s Magazine was lagging behind Shōgakukan’s Sunday in sales, and as part of an effort to feature more popular comics, Magazine asked Tetsuya Chiba to draw his first comic strip for a boys’ publication, to be serialized starting in Magazine’s first 1961 issue. For the boy protagonist in this serial, the baseball strip Chikai no makyū (“The Sworn Magic Ball”), Chiba used the same Takahashi-influenced facial design that he had adopted in his comics for girls’ magazines.

The popularity of Chiba’s The Sworn Magic Ball and subsequent work helped spread this character design among Japanese comics creators drawing for boys’ magazines, which turned the design into a new standard for comics protagonists in all major mainstream kids’ magazines, both for girls and for boys. This style proved enduringly popular, surviving into the late 1990s, when collected book volumes of successful magazine serials such as Sailor Moon first attracted widespread attention among comics readers in the United States and elsewhere, and it lives on in global bestsellers such as Attack on Titan and Demon Slayer. The role played by The Sworn Magic Ball in the establishment of this drawing style makes it a most appropriate cover image for Manga: A New History of Japanese Comics.

_______________________________________

Eike Exner is a historian of graphic narrative. He writes primarily on the history of the comics medium and comics in Japan (manga). His first book, Comics and the Origins of Manga, documents the popularity of American and other foreign comic strips in Japan between 1923 and 1940, and how Japanese artists created modern manga based on these comic strips. It received the 2022 Will Eisner Award for Best Academic/Scholarly Work. His new book, Manga: A New History of Japanese Comics, is a comprehensive history of manga from 1890 to today.

Add new comment