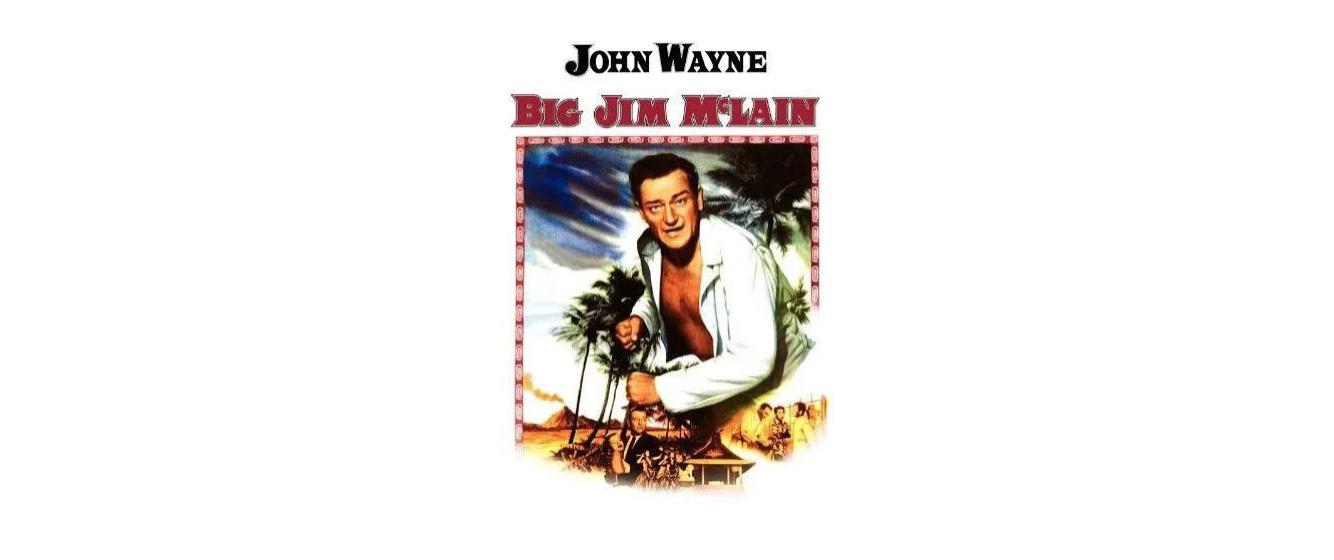

Red Hunting in Paradise. John Wayne's worst movie inspired my second novel

When the question “What was John Wayne’s worst movie?” is asked, inevitably two titles come up: The Conqueror (1956) and Big Jim McLain (1952). In 1956’s The Conqueror, a racially miscast John Wayne portrays Genghis Khan in terrible yellow-face makeup. In 1952’s Big Jim McLain, he plays a House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigator who makes his way to Hawai‘i to root out a communist cell. As someone of Asian descent from Hawai‘i, I should be revolted by both movies, but the truth is that because they’re both so hilariously terrible I can’t help but take a perverse ironic pleasure in their dreadfulness and revel in their high camp value. I can’t even watch the trailers with a straight face.

Big Jim McClain’s in particular should make you cringe and chuckle simultaneously:

In a way, Big Jim McLain, a travesty of a “historic” film, inspired my second novel, Red Dirt. It made me interested enough in Hawai‘i’s labor movements of the period to research what inspired so laughably awful a production, and I found something that really grabbed my attention: the HUAC investigators were far from real-life John Waynes, being mostly petty and ineffectual, and the actual communist cells here were not nearly as nefarious or dangerous as portrayed, but were just as petty as the HUAC investigators hunting them.

Cloaking personal vanity and greed in an ideological quest. I thought, holy shit, this is human failing at its most despicable. This is noir.

This is a book.

Big Jim McLain, while goofily making a point that communism is evil, doesn’t really define the actual ideology, nor does it address the opposing ideology of the main character. The film simply assumes that you know, or that you’ll take their word for it if you have no idea. I think most movie-going Americans of the time were more the latter. This ambiguity also made it convenient for the producers to rename the film Marijuana for overseas release with a convenient change in premise from communist villains to drug trafficking villains when the reception outside the U.S. was naturally lukewarm.

Trailer for "Marihuana" (1952) the overseas title for "Big Jim McLain".

I also found that this genuine lack of concern for ideals or understanding of them also existed in real-life Honolulu’s HUAC fiasco, where ideology on both sides took a backseat to the office-politics-like squabbles that defined the investigations and resulting hearings testimony.

I felt that the shallowness and self-importance of the players involved would make a great noir tale if I threw a corpse into the mix, and the second book featuring my protagonist from Kona Winds was born.

.

Of course, the real-life witch hunt in Honolulu culminated with the farcical Smith Act trial of the so-called Hawai‘i Seven, and the repugnant racist suggestion that Japanese Americans and other non-whites were at the forefront of communist agitation was anything but laughable. But this aspect, too, was an integral part of my novel.

.

The Hawai‘i Seven (l to r): Dwight J. Freeman, John Reinecke, Koji Ariyoshi, Jack D. Kimoto, (Attorney Richerd Gladstein), Charles K. and Eileen Fujimoto, Jack Hall.

Just as Japanese Americans during World War II were a convenient scapegoat for home front espionage paranoia because they were “socially visible” (though a number of German Americans and Italian Americans were also interned, the cases were isolated and a tiny percentage of a percentage of the attempted wholesale internment of the Japanese American ethnic population on the U.S. West Coast), the Red Scare had a face, and it was Asian. Postwar mainland China came under Maoist control, and though the Soviet Union (mostly other white people) were at the head of the cold war opposition, it was easier to demonize a less familiar face.

The image of Asiatic Communism persisted into the sixties: the Star Trek episode “The Omega Glory” (Season 2, Episode 23) which aired on March 1, 1968, featured a planet where a conflict was being fought by an oppressed society of white people called the “Yangs” (read: yankee) against ethnic Asians called the “Kohms” (read: communist). William Shatner saves the day without further fisticuffs with one of his trademark Captain Kirk orations. As a kid, I was just thrilled to see a bunch of actors who looked like me on television when I saw the episode in syndication (I love Star Trek’s original series). Not surprisingly, “The Omega Glory” is considered to be one of the critically worst Star Trek episodes, just as Big Jim McLain is considered to be one of John Wayne’s worst films.

In Hawai‘i, where Japanese Americans made up 40% of the population in the postwar period, Red Menace and Yellow Scare were synonymous. Though there has been a good amount of scholarship and nonfiction discourse on the matter, I had not really seen this aspect of Hawai‘i’s territorial history represented in fiction or popular culture.

Except in Big Jim McLain.

That made me want to set the record straight in terms of popular culture portrayals. A rebuttal of sorts. I made sure to touch on this aspect in Red Dirt, just as I created a cast of less-than-stellar human beings in both the HUAC camp and the local communist cell camp. Not a pretty picture of a pretty place, but hopefully more accurate and authentic than John Wayne seducing Nancy Olson on a rattan chaise lounge.

Sometimes inspiration comes from strange places, like shitty movies.

Read Red Dirt for my version of Hawai ‘i under the HUAC microscope in 1953.

.

_________________________________________

Scott Kikkawa is a fourth generation Japanese American raised in Hawai‘i Kai. Currently a federal law enforcement officer, the New York University alumnus is the author of three noir detective novels set in postwar Honolulu—Kona Winds, Red Dirt, and Char Siu.

Scott Kikkawa is a fourth generation Japanese American raised in Hawai‘i Kai. Currently a federal law enforcement officer, the New York University alumnus is the author of three noir detective novels set in postwar Honolulu—Kona Winds, Red Dirt, and Char Siu.

He has been honored with an Elliot Cades Award for Literature, and a crime fiction short story of his was selected as one of the “Other Distinguished Stories of 2021” in The Best American Mystery and Suspense 2022 anthology. He is a columnist and an Associate Editor for The Hawai‘i Review of Books. His short stories have appeared in six issues of Bamboo Ridge, Journal of Hawai‘i Literature and Arts.

Kona Winds and Red Dirt debuted on the Small Press Distribution fiction bestseller list and were featured in HONOLULU Magazine’s list of “Essential Hawai‘i Books You Should Read: The Next 134.”

Discussion questions

- What two John Wayne movies are called his “worst”? Which one inspired the novel Red Dirt?

- How were real communist groups in Hawai‘i different from how Big Jim McLain showed them?

- Why does the author find Big Jim McLain both cringe-worthy and oddly entertaining at the same time?

- How did the author use the movie’s exaggerations to write about hypocrisy and politics?

- What does this story show about the power of movies to shape how we remember history?

- Have you ever learned something important about your community from a “bad” or silly source?

Add new comment