Aaaan-punchi! Defeating the Problem, Not the Enemy in the Era of High-Speed Growth

It’s true that American children of a certain generation (Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z) “grew up with Japanese anime” as written in a previous post “Generation Z is Japanese” (13 February, 2024). However, American children never got hooked on one of Japan’s most popular anime/manga titles ever: Anpanman (Go! Red Bean-paste Man!, manga 1973 - 2013, anime 1988 - present). Anpanman is a superhero whose main fans are children in kindergarten and the early elementary school years.

Japanese children grow up watching Anpanman!, and reading the manga from which it was born: Anpanman, created by Yanase Takashi. According to Michael Furmanovsky in a previous blog post, Yanase noticed that American superheroes like Superman fought crime, but they never got dirty, never suffered themselves, and their solution to the problem was always just to eliminate a bad guy. Yanase created Anpanman in contrast to that theme. Instead of fighting a specific villain, Anpanman fights hunger. He does so with a sunny attitude, a willingness to work with friends, and compassion. He also feeds the hungry with his own red-bean-paste (anko - the “an” in Anpanman) face when they need it. Rather than eliminating the villain, Anpanman fights the problem. Though he often sends the bad guy off in an episode with a single punch to the chin, in the process yelling "an-punchi" - a play on his name. That one punch usually ends the episode.

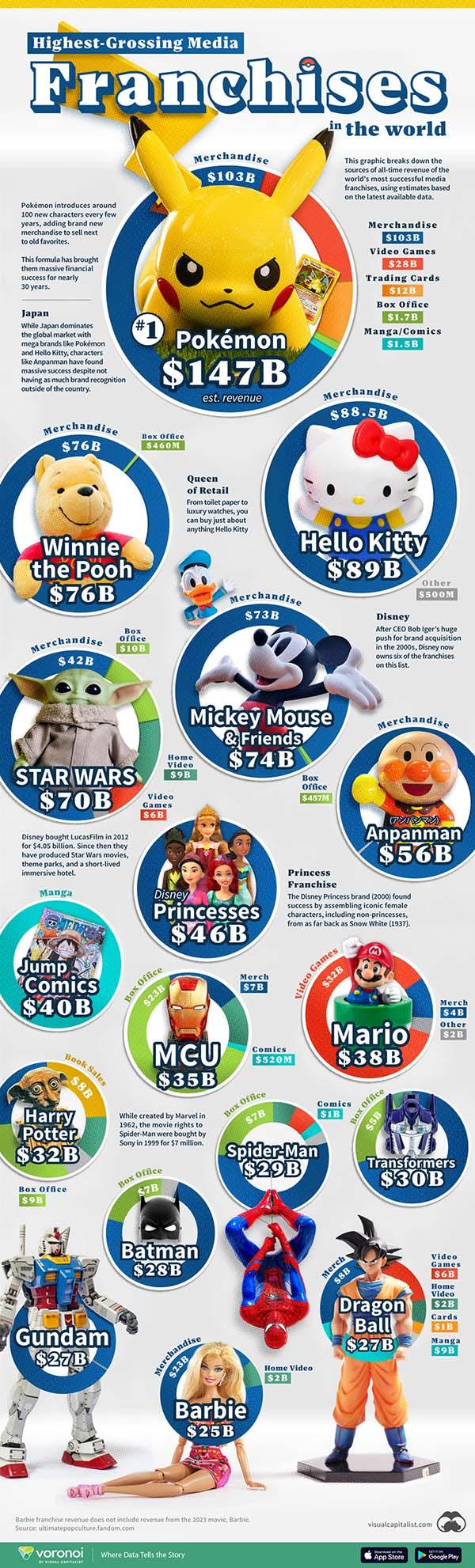

Anpanman, which is now ranked as one of the top character-driven properties in Japan (it was ranked number 1 in Japan by CharaBiz Information in 2011, ahead of Pokemon, Mickey Mouse, and Hello Kitty), is not well known outside of Asia. Yet, it is the #6 largest media franchise in the world, larger than Marvel Comics Universe, Harry Potter, Spiderman or Barbie!

This may be due to two key issues that impede the process of ‘glocalization’ - the methods and techniques by which globalized products are made popular in various international markets through modifications that help them fit in with local culture - for example, the difficulties in translating Japanese word play into non-Japanese languages. The second is Japan's cultural and economic experience in the period from 1960 to 1989, when Sore ike! Anpanman became popular, was in many ways dissimilar to the experience of Western, developed states.

Japanese children grew up knowing about the “Anpanman March”!

The translation problem begins with the names of the characters. Anpanman, for example, has no real equivalent in many other languages, largely because red bean paste sweets are most common in East Asia. Perhaps that is why it was successfully glocalized in Korea as Hoppangmaen (1996), with hoppang being a similar bun filled with red bean paste. Media companies could have glocalized him to the West as “donut-head,” or something like that, but finding a food-based name that evokes the same kind of childhood excitement in children and nostalgia in parents that Anpanman’s name does would be difficult. However, the problem does not end with the main character. His creator, mentor, and the owner of the house where Anpanman lives is “Jamu Ojisan” - simple enough: “Uncle Jam.” How about Jamu Ojisan’s live-in assistant, whose relationship with the chef is, in true early-childhood fashion, oddly undefined: is she a live-in employee, a sister or cousin, a spouse? In the show this is not clear. And her name is “Batako-san” - Miss Butter. Then we have “Shokupanman” - Mr. White Bread, “Carepanman” - Curry Donut Man, and Melonpanna - Melon bread girl. Here is where the problem begins. All the good characters are designed around food or domestic chores, and all the bad characters, such as Baikinman (“germ man”) are designed around bacteria, mold, overly excitable behavior, and other such things that children are warned to avoid. These things are sometimes vastly different, or at least conceived of differently outside of Japan.

One character, for instance, who appears in only a couple of episodes, is “Nanka Henda san” - this is actually quite complex wordplay. Nanka Henda san is a confused character who is never satisfied with the status quo and wanders around saying “nan ka hen da” (something is not right). But it also sounds like the Japanese pronunciation of the American name Henderson. Such Homophones are a foundational part of Japanese word play, and form the basis of many joke punchlines. They are in a sense multilingual puns. In another example, a Japanese friend knows I live in Hawaii, so he constantly asks me “ha wa ii ka?” This actually means “are your teeth okay?” It is amusing wordplay using homophones from two languages. So How might one best translate “Nanka Henda san” to, say, American English? It wouldn’t have the same effect to call him “Mr. Henderson” - though that might be the best choice. Another possibility is “Mr. That’s Strange” or even “Uncle Detective.” Neither captures the character, but worse, using any of those three makes much of the dialogue around the character, which also plays on the international pun, absolute nonsense.

The point here is the difficulty and likely cost involved in translating and localizing Sore Ike! Anpanman! If the show were localized in multiple countries, as Pokemon has been, the cost of hiring skilled translators and reworking storylines that rely on this wordplay would be enormous, and might not have the endearing effect that it has in Japan. Personally, I’m not sure even American toddlers would be interested in stories about food they have no access to in the grocery stores they experience daily.

Tokyo in the 1970s shows a High Speed Growth Japan

But that’s not all. Anpanman is tightly interwoven with the Japanese experience of post World War II modernity. From 1960 to 1973 Japan experienced the “Era of High Speed Growth,” and from 1973-1989, The “Bubble Economy.” These were the years in which Anpanman was born and became popular. In the late 1960s, Japanese government policy was to double the income of Japan’s citizens. Using a combination of international trade and industrial policy, Japan succeeded in this goal by 1979. During the 1980s, increasing personal incomes led to increases in consumer purchasing. The Japanese economy became more powerful and grew at a rate of 10% per year. This was a global historical record until China's high growth in the 1990s. In Japan, it led to land price speculation particularly in the cities. That created a real-estate boom and by 1988, the land under the Waco department store in Tokyo’s Ginza Ward was as valuable as all the land in Manhattan.

Japanese children growing up in these two eras experienced a change in life context. As Japan moved from the difficulties of postwar recovery to, through government shepherding of the economy, a nation where employment was high, several things occurred. Japanese children were sent through a system of education designed to train them to be reliable and thoughtful workers in a growing economy, and they were sorted out for future employment roles through this same education system. The idea in Anpanman that all the good guys work together, pooling their individual strengths to defeat the problems they face echoes the way in which Japanese children were taught that corporate culture and the national economy worked. Not everyone can be a corporate manager or a government bureaucrat - or Anpanman. But that’s okay, because for each Anpanman we need a tough sidekick with a never-fail attitude like Carepanman, cute office ladies who make coffee and keep us cheerful, and can do their jobs well when necessary like Melonpanna; teammates who see the dark side of things and don’t often participate, but come to everyone’s aid in the clutch with great power like Rollpannachan, and inspirational heroes in white who might lose their power with a little dirt, but motivate us all to be our best selves like Shokupanman. The family, the class, the company, and the nation are teams to which you belong, and everyone has their place. School is where the sorting into places happens, and teamwork is what, in 1970s and 1980s Japan, was making the nation rich.These were values that were shared with the rest of East Asia. When BTS compared themselves to heroes, they compared themselves to Anpanman, not to Superman.

Anpanman taught children to be consumers, to see themselves as team players, to be kind to each other and recognize each other’s strengths and accept each others’ failings. It socialized Children into a Bubble Era society in which the individual thrives because the group thrives, and helped them accept their sorting into the different hierarchies of society of the time. In that sense, Anpanman is very much a Bubble-era anime. This same preparation, though, did not prepare many children who grew up in the late 1980s and early 1990s for the collapse of the Bubble Economy, and the social unraveling and economic malaise that followed. It was as if Baikinman - Mr. Bacteria - the primary evil character, had succeeded in causing great harm, and Uncle Jam had forgotten the recipe to make Anpanman come alive. The characters kept playing their roles on TV, but in the real world, the anime’s audience was finding, after 1989, that the team was breaking up.

In a future post, I will look at One-punch Man, the post-bubble version of Anpanman.

Add new comment