Review of Eike Exner, Comics and the Origins of Manga: A Revisionist History, Rutgers University Press, 2021.

Go to bookstores, and you will notice that they have manga sections. And there are kids sitting on the floor browsing through the manga. Although in places like the United States, bookstores have shut down over the past decade, one can easily see translated manga, a form of Japanese comic books and graphic novels online. With the Internet Revolution of the 1990s, (often illegally) translated manga made its way into children’s and teenager’s bedrooms throughout the world. And far from being just for kids, manga has a whole range of subjects, appealing to children, teenagers, adults, and many are geared specifically for men and for women. Manga is the material upon which most anime (Japanese animation) is based.

Today, the global manga market size is enormous. According to a report by Grand View Research, the global manga market was valued at $15.6 Billion in 2024 and is expected to reach $ 42.5 Billion by 2030.

As I pointed out in an earlier post, today’s worldwide Generation Z grew up with Japanese popular culture as an integral part of their lives. Manga is one of those Japanese cultural products that has caught on with youth worldwide. People identify manga with Japan, as a unique Japanese invention.

But what if I told you that what we call Japanese manga is actually modern and transnational in origin?

As Eike Exner shows in his award-winning Comics and the Origins of Manga: A Revisionist History (2021), manga’s origins come from early 20th century American-inspired comics. In other words, what we call “Japanese” manga is actually a Japanese adaptation of American-style comics based on a late 19th century invention, the phonograph and its ability to record audio sound. Intrigued by this idea, I reached out to him, and he stressed to me that comics weren’t specifically an American invention but more a “modern” invention, to avoid turning this into a “West vs East” issue. In other words, Manga is not specifically Japanese or specifically different from “Western comics”.

The Chōjūgiga theory and supposed Japanese origins of manga

.

One school of thought identifies the Chōjūgiga (animal scrolls) from the 1200s found at Kōzan-ji temple as the origin of manga. (Public domain photo).

I’ve taught a university class on manga and anime since 2003. Like many other academics, I used to trace the origins of manga from as early as the 12th century, stemming from the Chōjūjinbutsugiga also known as the Chōjūgiga(animal scrolls) found at Kōzan-ji temple in Kyoto.

These are incredibly cute scrolls probably made by bored monks, depicting animals acting like humans: a frog as the Buddha, or a fox as a princess. If one believes that manga came from these scrolls, then the Japanese were creating Mickey Mouse type anthropomorphic creatures centuries before Mickey made his debut in the animated short Steamboat Willie(1927).

In the 19th century, woodblock prints became popular among the large urban populations of Tokugawa Japan. So the story goes, this cartooning tradition received the name “manga,” meaning “random pictures” (漫画) and it was used to describe woodblock prints of random sketches, like people bathing. Then, with the opening of Japanese ports to European trade in the 1850s came a flood of Western influences. In the 1870s, European style political cartoons entered Japan, and fused with the native Japanese tradition of woodblock prints and scrolls to create what we now know as manga.

Now I realize I have been teaching all this wrong for twenty years.

Audiovisual manga: the phonograph meets comics

.

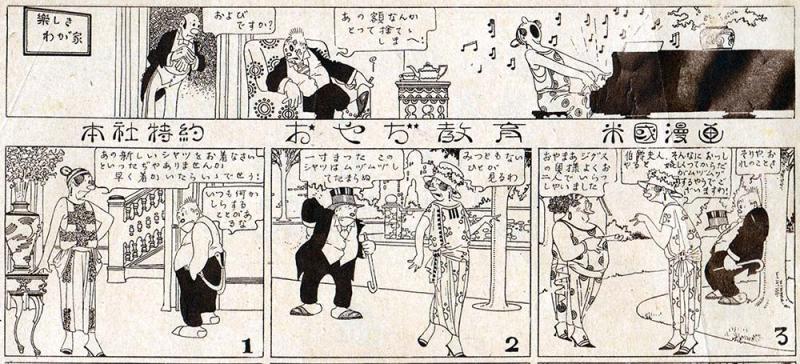

“Bringing up Father,” (1912 - 2000) known as “Oyaji Kyouiku” in Japan, influenced Japanese manga and was described as “American comics” (beikoku manga 米国漫画). Source.

Exner lays out the case that little of what we call Japanese manga, with its complex storylines, cinematic pacing, and complex dialogue was seen in pre-20th century works. There are two schools of thought, one that looks at the Chōjūgiga as the origin of manga, while the other sees the scrolls as interesting in their own right, but unrelated to manga. Exner belongs to the latter school, and makes a convincing case in his book.

Rather than looking back in antiquity for the origins of manga, Exner argues that what we call manga today took its form from early 20th century comics that appeared in American newspapers. These comics were translated and regularly appeared in Japanese newspapers to draw in readers.

And what made the American comics so appealing? The invention of the phonograph influenced the creation of what Exner refers to as audio-visual comics around 1900. In the past, speech as it was spoken was not represented by what we now call speech bubbles. Sometimes there would be a narrator explaining the action, or words on the side representing the thoughts of the characters, but nothing to represent the words as they were directly spoken and heard by other characters.

.

Pantomime comics like Rudolph Dirks Katzenjammer Kids (1897) was part of the rise of modern visual culture in the mid 19th century. (public domain)

How did modern comics come along? In the middle of the 19th century, modern visual culture took root in Western societies, such as stereoscopes and photography. Comics changed during this development of visual culture. “Pantomime” comics, like the early Rudolph Dirks’ Katzenjammer Kids (1897) and Frederick Burr Opper’s Happy Hooligan (1900) started out showing stories through visual humor rather than explaining them.

These pantomime comics were the direct predecessor to the next big development in modern comics. The invention of the phonograph in 1877 allowed for the first time, direct speech to be recorded and listened to again. The gradual adoption of the phonograph in everyday life by the early 20th Century as the price of phonographs came down had a direct influence on what Exner calls “Audiovisual comics.” Comics mimicked the phonograph, and one could read speech again and again, just like listening to a phonograph. These speech bubbles, representing direct speech, came into widespread use in comics after the phonograph also came into widespread usage.

Largely forgotten now, George McManus’ Bringing up Father (1913) was the world’s most popular comics at the time, widely syndicated and popular in places like China and France. Think of it as the Dragon Ball Z of the early 1900s. This comic strip was translated into Japanese as Oyaji kyōiku (オヤジ教育) and published in the Asahi Graph in 1923. Exner points out how this comic, the first audiovisual comic in Japan, caused a sensation and led to Japanese newspapers publishing translated American audiovisual comics to gain readership. In fact, being American was a sign of its modernity! Japanese newspapers advertised their comics as Beikoku manga米国漫画, or “American comics”.

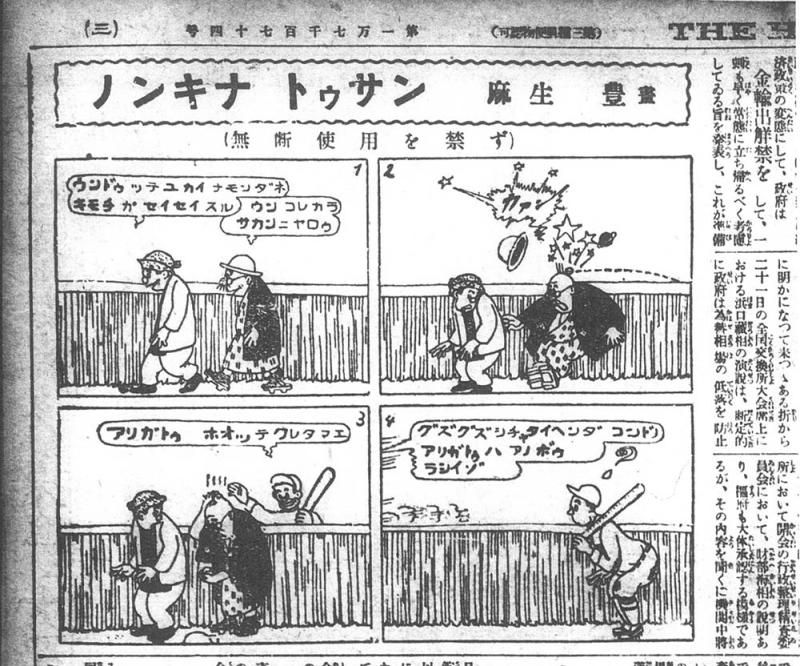

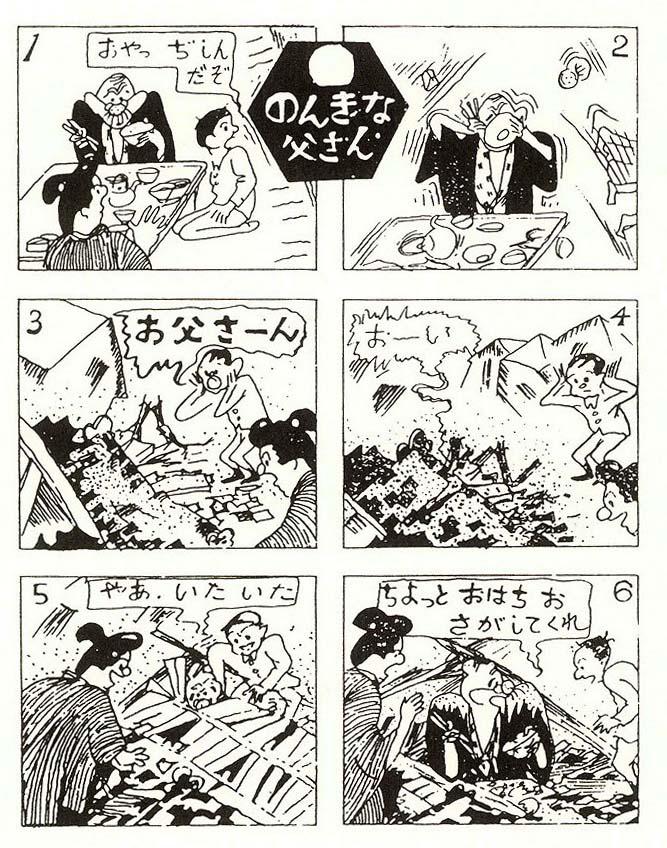

Keeping with Japan’s tradition of domesticating foreign ideas, Aso Yutaka domesticated this idea and created the first smash Japanese comic, Nonkina Tōsan (“Easygoing Daddy"), which appeared in various formats and newspapers from 1923 to even after the war in 1945. This comic spawned merchandise, and even animated and live action films.

The Japanese translations of American comics spawned other Japanese versions of American comics. Thus, the DNA of Japanese manga can be traced to modern audiovisual comics, not a thousand years old tradition rooted in Japanese culture.!

Against the Chōjūgiga theory

Did the Chōjūgiga scrolls or 19th century Western-inspired comics influence Japanese manga? Exner convincingly argues neither: early manga prior to the 20th century were more like narrated illustrations, rather than stories with dialogue. He shows how there was no spoken dialogue in 19th century manga. The Chōjūgiga, for example, has no dialogue, and no cinematic sequencing. The early 19th century manga were just random pictures such as people swimming, with no dialogue or storyline. Even the comics that appeared in Japanese newspapers in the late 19th century could be characterized more as illustrations to accompany a written narration.

Japanese editors in the 1920s had difficulty figuring out how to translate and adapt American comics for Japanese audiences. Japanese is normally read from right to left, and also vertically. Editors had to reverse the layouts of the American comics, changing them to fit the right to left Japanese pattern.

.

Nonkina Tōsan, when it debuted in 1923, was written Western style, horizontally, from left to right, and arranged left to right in panel order. Nonki na Tosan,” Hochi Shimbun, Nov 23, 1924. Picture courtesy of Eike Exner.

Many editors eventually decided to keep the American reading order (left-to-right) and even write dialogue American style horizontally from left to right. Early Nonkina Tōsan followed the layout of American comics. This layout was popular because, as Exner notes, it gave the comics a modern “American” feel. Readers had to mentally flip their reading order and thus read the comics American style, adding to the exotic nature of the comics. Today, Japanese publications and websites still use this reading order, with horizontal script reading from left or right, while interestingly, manga has reverted to the traditional style and is written vertically from right to left.

As previously mentioned, publishers would regularly refer to the comics as “American comics” or to add to their appeal. The foreign reading order only added to its modern mystique. How interesting that what we call Japanese manga was initially known in Japan as an American style of comics!

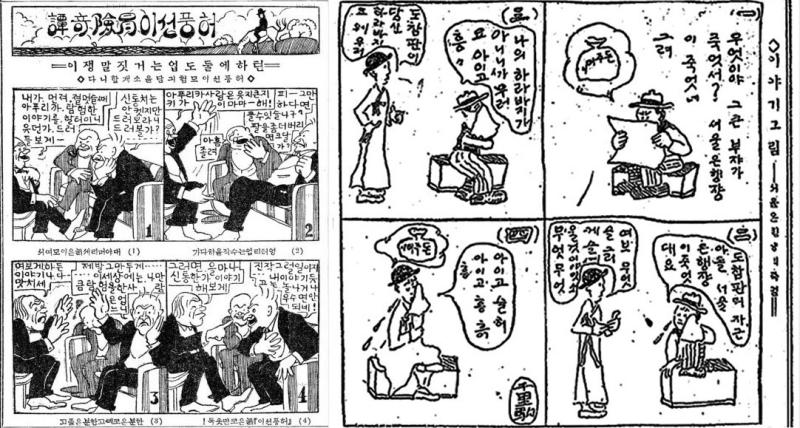

American audiovisual comics in Asia

American comics not only revolutionized the Japanese comics scene at the turn of the century, but also influenced the East Asian comics scene. Japan, throughout most of modern East Asian history, has played a role of taking Western influences and domesticating it to fit Japanese culture. Other nations in Asia have taken these Japanized influences and localized them. Comics is one of these adaptations that spread throughout East Asia, as seen in Korea. Exner gave a speech at a conference in 2024 detailing his research into Japanese influences on Korean and Chinese comics. Intrigued, I did some online research. Park Inha points out that Korean cartoonists used comics as satire during the era of colonial rule, until the Japanese repressed them. Given the cultural similarities of Japanese culture with East Asian culture, as well as the linguistic similarities from using Chinese characters in writing, it can be hypothesized that Chinese and Korean authors got their inspiration from Japanese adaptations of “Bringing up Father,” as well as the Japanese localization “Nonkina Tosan”. For some reason, Ahn Seok-joo’s “Adventure of a Braggart” reminds me a lot of “Bringing up Father”.

Thus, manga could be seen as another example of the Pop Pacific – a American influenced transpacific culture that has been given national labels like Japanese manga, or Korean manhwa, or Chinese manhua. And this “Japanese” form of American comics has now grabbed the imagination of youth worldwide.

Go read Exner’s book with an open mind. Like me, it will probably take time to digest the idea of the “modern” origins of “Japanese” manga. How interesting that readers around the world, when they read Japanese manga, are actually reading something with a hidden lineage from modern audiovisual comics.

Discussion Questions

- Manga is often seen as uniquely Japanese. What does the article suggest about its actual origins?

- How did the invention of the phonograph influence the way comics developed in the early 20th century?

- Why were American comics like Bringing Up Father so popular in Japan, and how did Japanese editors adapt them for local readers?

- How does this article challenge the idea that manga grew directly from traditional Japanese art forms like the Chōjūgiga scrolls?

- What does the story of Nonkina Tōsan show us about how Japan adapted and “domesticated” foreign culture?

- The article describes manga as part of a larger “Pop Pacific” culture. What does this mean, and how might it change the way we think about manga, manhwa, and manhua?

Add new comment