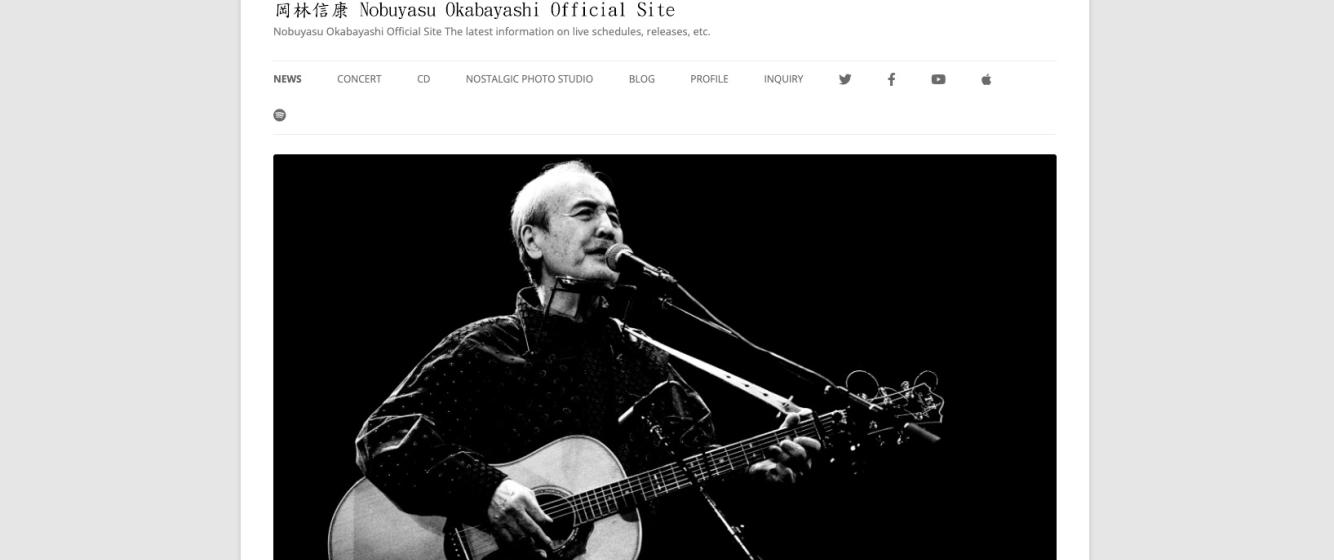

Screenshot of Nobuyasu Okabayashi’s official website, September 2024

Okabayashi Nobuyasu and the Rise of the Pop Gods

Hi everyone,

Well, we are back after taking the summer off! I hope you also had a refreshing summer. To start off the new season of the Pop Pacific blogs, we welcome back Dr. Patrick Patterson after his sabbatical and busy spring. Pat is one of the co-editors of this blog, and he is an expert on early Japanese modern popular music. If you have a chance, go to the library and check out his amazing work, Music and Words Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887–1952 (2018). To the best of my knowledge, this is the only English language work that details the development of the early Japanese record industry and popular music market between 1887 and 1952. Pat is also a specialist on 1970s - 1980s Japanese pop. You city pop fans (but Pat doesn’t think there is such a thing as “city pop” will learn so much from his writings. Please enjoy and learn from his latest work!

-- Jayson Chun

It was summer, 1970 and the “God of Folk” (fōku no kamisama - フォークの神様) stood on stage, his guitar held like a weapon as he prepared to go into battle, cowboy hat on his unkempt head, bearded face sweating. He began to strum the opening bars to one of his recent, and very popular songs - “The Fuck Off Song (Kusokurae bushi くそくらえ節).”

The song was popular even though it could not be played on the radio. The massive crowd of folk fans and hippies in the outdoor concert venue went wild, briefly drowning out the acoustic guitar he strummed.

Then, he stunned them. His backup band began to play, and they were using - electrically amplified instruments. An electric guitar and bass cut through the sound of the cheering audience with rock chords as Okabayashi Nobuyasu, following a path parallel to his American counterpart Bob Dylan, betrayed the most central ethos of the very folk movement he epitomized, and rock music echoed through the Hibiya Outdoor Auditorium. Folk, it seemed, was dead; long live rock.

But Okabayashi did not abandon folk. “The Fuck Off Song” was about the expectations society put on young people to get good grades, go to the right college, and get a good corporate job. It was protest folk at its finest - humorously inappropriate with a serious question about the values of society and the effects those values had on youth. As the song started, Okabayashi sang,

Once upon a time, a teacher told his students

If you don’t cry when your test score is less than perfect you’re a failure

Fuck off, fuck off

In that kind of world only a computer can be a good person

This was the peak of the folk movement in Japan and the moment it disappeared. Okabayashi had been on the scene since 1968. A member of the Workers’ Music Council and a socialist whose own early life had been about questioning all of his received values, Okabayashi was a genius at writing music that skewered the status quo. His choice to “go electric” was at least symptomatic of a major sea-change in Japanese popular music after 1970. What follows is a summary of that change, based on the analysis of Michael Boudaughs.

Okabayashi performing “Sanya Blues” (1969). Sanya is a slum district in Tokyo known for its homeless population and day laborers.

Okabayashi Nobuyasu was part of a new generation of Japanese born just after the end of World War II (Okabayashi was born in 1946). Not having grown up with the prewar cultural norms, nor with the war fever and nationalism that characterized the immediate prewar years, the youth of Okabayashi’s generation did not have attachments to prewar popular music or the cultural norms that underpinned it. They were impatient to get on with their lives, and with redeveloping Japan after the end of the U.S. Occupation. They did not agree that American-style capitalism was the best way forward for Japan, nor that an alliance with the United States would be useful for the Japanese people.

That Japan, despite its loyalty, chafes under U.S. leadership is no secret. It has appeared recently as a theme in popular films like 2016’s Shin Godzilla, and 2019’s Godzilla Minus One, in both of which, to save itself, Japan has to solve the giant monster problem on its own. This argument - that Japan should be more independent in its relationship with the United States, has been going on since the U.S. Occupation. Okabayashi’s music, and that of other folk singers including Mike Maki and Yoshida Takuro, was a way for the younger generation to stand against both unrestrained capitalism and dependence upon the United States even while rejecting prewar Japanese nationalism. The folk generation were dissidents, looking for a third way in which Japan could chart its own course without war.

Dissident in an era of High-Speed Growth

_

The steel plant of Nippon Steel Corporation represented the high-speed growth of the 1960s and 1970s (public domain photo)

The problems of the occupation and the ambitions of the postwar generation collided. Many young people did not buy the post-war system. They rejected wartime militarism. But they rejected American capitalism as well. They did not wish to be under the control or even influence of the United States. Okabayashi fit the needs of this generation perfectly. He was a labor union activist. He was a socialist. He was just who the youth wanted to hear from in a new Japan that was a hotbed of citizen activists trying to make the country what its people wanted it to be. He even spoke, in a way, a different language - he protested and exhorted through music, rather than political speeches, and played concerts rather than organized campaigns, and his songs stood for Japanese independence, a return of confidence in Japanese culture, and, more than anything, resistance to the occupation of Japan and control of its government, economy, and people by the United States and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP).

When, in 1949, Northern Korea invaded the South, Japan became a storehouse and manufacturing center for American military supplies. It became the American rear area. Soldiers went to Japan for R&R. In the developing Cold War, Japan was one of the walls against Soviet Communism. The U.S. released Japan’s wartime bureaucrats from prison and rehabilitated them because they knew how to get things done. They went into government. They rejoined major corporations. They had the right experience and were anti-communist to boot. The government received new powers to break strikes, and workers began to lose power. The Japanese government became close with the United States. All of these changes were the opposite of the hopes and ideals of Okabayashi, his fans, and the new generation of Japanese. This led to a new deal with the Japanese people - less freedom in exchange for growing wealth. Okabayashi, along with many young people, rejected that bargain.

From 1955 to 1973, Japan’s economic growth was the fastest in a fast-growing world economy. Growth averaged 10% per year, doubling the nation's wealth every ten years. Incomes doubled as well. Japanese citizens became members of one of the wealthiest nations on earth. They expected their children to do well in school. That would allow them to get corporate jobs to support the nation. In turn, the corporations and the state would support them with lifetime employment. Women became homemakers, supporting Japan by supporting their husbands. Japanese youth, like Okabayashi, saw the free choice they had expected wrenched away. Instead they received a narrowly defined future: that of the salaryman. Many saw this as a trap.

Okabayashi was their spokesman. He encouraged people to imagine a different future, and recognize that Japan had a choice. He did so with humor. He became, ironically, a national celebrity even before he released his first album. His concerts sold out, and his protest music was on the lips of an entire generation.

Okabayashi Nobuyasu with Happy End: “Kyo wo koete,” 1970

Okabayashi was a national youth hero until, in 1970, with Happy End backing him up, like Bob Dylan in the United States, the genius betrayed his folk roots and went electric. When the audience noticed the amplified speakers on stage, and the electric guitar and bass, they were shocked - the folk icon had eschewed folk music. It was the equivalent, musically, of reversing his values and critiques of the postwar system. If he could leave the norms of folk music behind, couldn’t he betray the youth and their movement as well? Folk was about social problems and finding ways forward for everyone. Rock seemed at the time to be about amped guitars and belly-button-watching self-absorption. By leaving folk behind (a musical move that Okabayashi and other skilled musicians frequently do in the course of evolving careers) he had signaled to his followers that perhaps he was just a musician after all. The disappointment, there at the concert in 1970 and afterward, was palpable. The prophet of a new generation, like Dr. Suess’s Lorax, had left the stage, and his fans were not sure what to do next. Like the failure of the anti-ANPO treaty protests, Okabayashi’s electric move felt like one more nail in the coffin of the postwar hopes of a new generation. His move also changed the music industry altogether in Japan. After 1971, Okabayashi disappeared from stage performances for a few years. He would eventually come back, having remade himself again. But in the meantime, Japanese popular music was looking for a new direction.

“Happy End (Band).” In Wikipedia, March 29, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Happy_End_(band)&oldid=1216120773.

“Nobuyasu Okabayashi - 自由への長い旅 (Jiyū e No Nagai Tabi) (English Translation).” Accessed May 27, 2024. https://lyricstranslate.com/en/jiy%C5%AB-e-no-nagai-tabi-long-journey-freedom.html.

Bourdaghs, Michael K. Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop. Asia Perspectives: History, Society, and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Seraki, Dimitri. “New Rock and Happy End - Origins of Japanese Rock.” Fullfrontal.Moe (blog), December 2, 2021. https://fullfrontal.moe/new-rock-and-happy-end-origins-of-japanese-rock/.

Tobe, Name Nobuyasu Okabayashi Role Singer Albums Mirumaeni, Watashi Wo Danzai Seyo, Kuruizaki, うつし絵, ラブソングス, セレナーデ, Oira Ichi Nuketa, et al. “Nobuyasu Okabayashi - Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia.” Alchetron.com, August 18, 2017. https://alchetron.com/Nobuyasu-Okabayashi.

Add new comment