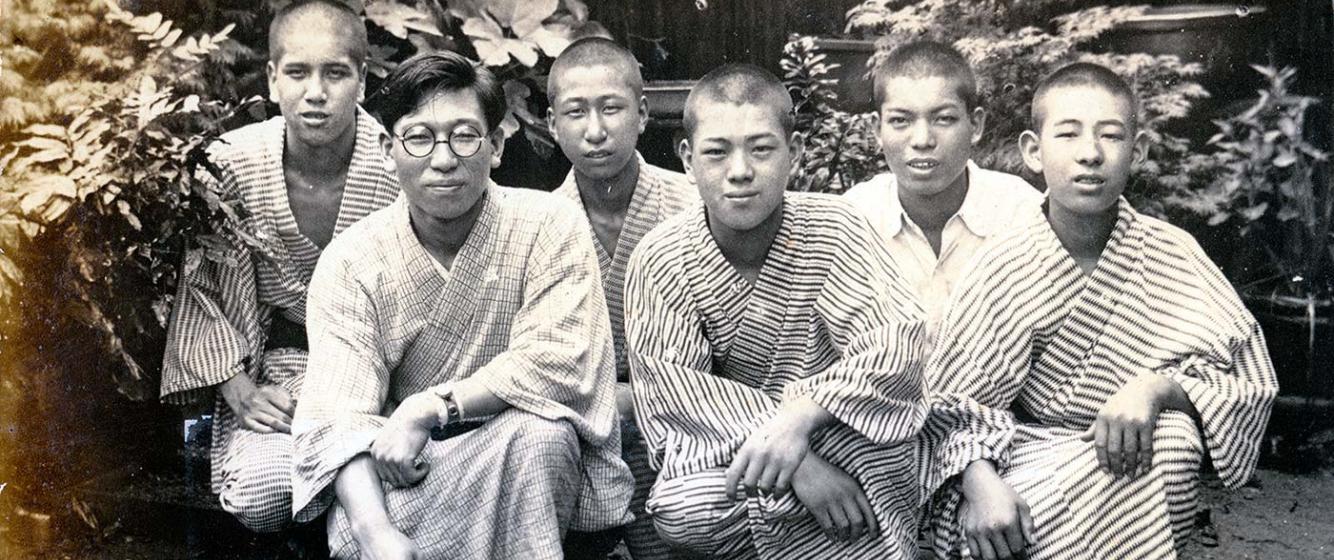

Group of Japanese boys in yukata in Nippori neighborhood, 1934.

Tokyo Ondo

Planning a trip to Tokyo with a friend recently, I mentioned that Tokyo is more than just the world’s largest city. With a population larger than that of many nations, it certainly is that. But, I told my friend, if you visit, you learn very quickly that Tokyo is a collection of neighborhoods. Each neighborhood has its local culture and history, and residents identify with that culture.

When you are in Tokyo, asking a Tokyo resident where they are from gets you their neighborhood. They never say “I’m from Tokyo” unless they are outside of the city. So people you meet will tell you they are from Suginami, or Taito, or Katsushika, or Shinjuku. Tokyo people – often known as edokko, for children of Edo – the former name for Tokyo – identify with these neighborhoods and their culture. When they go to work, they identify with the work culture in the neighborhood where their workplace is located. Chiyoda and Akasaka are high-prestige areas to work. Tokyo is a complex network of neighborhoods, rather than a single great city.

In October 1932, the city of Tokyo became the second largest city in the world by annexing these adjacent rural areas and villages. It was a big deal; a matter of local pride. It involved adding 20 new wards (neighborhoods) to the city to make a total of 35. The process was on display in the recent NHK Morning Drama Ranman, about a famous Japanese herbologist. One of the minor stars of the story is Shibuya, which is now a famous district within Tokyo but was, in the early twentieth century period when the drama is set, a village on the outskirts of the city. The main character’s wife, Sueko, is important in building Shibuya as a business destination. She is the very successful owner of a tea shop. A part of this post is the story of Tokyo’s growth to incorporate so many villages and the identities of so many people who come from those neighborhoods. The neighborhood that this story centers on is Marunouchi – the area where Tokyo station sits astride one of the largest transportation hubs in the world, fronting Japan’s imperial palace, and some of the oldest and largest corporations in Asia.

The first half of 1932, the year Tokyo expanded, was a busy period. It was the start of a tragic period in Japanese history. And yet people wanted to dance. That year Nakayama Shimpei wrote an infectious tune for an urban bon festival in Tokyo’s Hibiya Park in July. Residents became caught up in the song and the dancing. “The circle of dancers “quickly encompassed other districts within and outside of Marunouchi, where a bon dance fever took hold.” As Japan began falling into the desperate years of the trans-war period, people were not simply caught up in grim obedience to the state. Life in Japan remained complex and there was room for joy and entertainment. Nakayama celebrated the diversity of Tokyo culture by writing folk songs for the city.

Nakayama wrote his song, which he at first called “Marunouchi Ondo” on a commission from a businessman. A man named Tomikawa, owner of the Hana Tea Shop and a Yūrakuchō neighborhood booster, asked him to celebrate the neighborhood. Tomikawa wanted a Bon Dance because it would be good for local business. Unusual in this scenario is that the Bon Dance was not to be sponsored or even held on the grounds of any local temple or shrine. It was a purely secular affair, designed to promote business; a Chamber of Commerce festival, rather than a religious festival in honor of the dead. Nakayama described how he received the commission:

“Around Shōwa 7 (1932), I was soaking in a morning bath with the head of the Tomikawa family, a Marunouchi Yūrakuchō booster and the owner of the Hana Tea Shop; he said to me that for the sake of prosperity, once this summer we should do a bon odori, and from that conversation I created the “Marunouchi Ondō.”

Tomikawa had heard Nakayama’s “Tokyō kōshinkyoku,” and decided that Nakayama would do the job right. So “Marunouchi Ondō” was never designed to be a popular song on record. It was the theme song for a local business festival meant to draw customers to the Yūrakuchō area. It did fit roughly within a tradition of songs celebrating specific places for which Nakayama was already quite famous: shin min’yō (new folk songs). However, most shin min’yō celebrated locations in the countryside – famous views, quaint villages, and, one of Nakayama’s favorites, ski resorts. To write one for Tokyo was unusual.

Nakayama and Tomikawa created the song, planned the date, and then found that the Tokyo police did not give permits for large public gatherings. This was because of the 1925 Peace Preservation Law, designed to maximize control of urban areas and large crowds to prevent riots and political protests. The police were willing to make an exception if all participants wore yukata – the thin cotton summer “kimono” tied with a simple obi. This was probably because of the difficulty in hiding weapons and protest signs inside the light cotton garments, and the near impossibility of running while wearing them. So the Hana Tea Shop began selling yukata for the bon dance and the police allowed it to go ahead. Apparently, the windfall profits from the unexpected yukata sales made Tomikawa quite pleased, as well.

There was an unexpectedly large turnout of participants at Hibiya Park. The market was irresistible, and record companies quickly capitalized on this “bon odori fever.” The residents of Tokyo found themselves “pulled into an ondō maelstrom” by 1933.[1] The popular culture feedback loop was already on its second go-round, and in the summer of 1933, Nippon Victor closed the loop with consumers again by offering a recording of the song retitled “Tokyo Ondō” (Tokyo Dance) for sale. It was a market success, selling half a million copies in that year alone.

The Ondō boom had begun. Before 1935 was out, every one of the 35 neighborhoods within the newly expanded City of Tokyo had its own Ondō to be performed at Bon festivals. Residents of these neighborhoods came to see them as a part of the neighborhood’s identity, as much as the culture of the area and its history. Nakayama had, once again, inadvertently created music that wormed its way into the cultural fabric of Japanese history and identity by creating music that was unabashedly for everyone’s enjoyment, and then by putting that music in easily accessible form on record.

Sources

Nakayama, Urō. 1980. Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku/Nenpu. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha.

Nakayama, Shimpei. 1935. “Nakayama Shimpei Jiden " Chūo Kōron.”

Patrick Patterson, Music and Words: Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952, New Studies in Modern Japan (Boston: Lexington Books, 2018), 1952. 109-112.

Saburo Sonobe, Nihon Minshū Kayō Shiron (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, 1962).

Saburo Sonobe, Enka Kara Jazu E No Nihonshi (Shokosha, 1954).

Showa Ryūkōkashi (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, n.d.).

Add new comment