Fig. 1: Worker riding in a field. (Photo courtesy of Tzu-ming Huang)

‘When the Situation Is Bad, You’ve Got To Be Strong’

The following narrative was constructed by Isabelle Cockel, based on an interview that she conducted with May (pseudonym), a Filipino expat in Taiwan.

When did I come to Taiwan… Was it in 1988? No, it was in 1987. I gave birth to my eldest son in 1988. So yes, it was in 1987 when I came to Taiwan. How did I come? It was through negotiation. My mother’s friend told her about having me get married with a Taiwanese man. Around that time, there were Taiwanese men looking for Filipino women for their wives.

Back then, I was only 19 years old and had just finished senior high school. I had never had a boyfriend before getting married. I was the only child and my mother was poor. I agreed because I had a beautiful dream: I’d go to Taiwan and I’d move my mother and grandmother to Taiwan to stay with me. So I came.

There were two of us who were brought to Taiwan by a Taiwanese man. The man introduced me to three Taiwanese men, but I said no to all of them. One of them was disabled; another one smoked and chewed betel nuts. The Taiwanese matchmaker was agitated. He called my mother, telling her that I’d have to hurry since I came to Taiwan on a tourist visa, which lasted only one month. My mother then told me that If I failed to get married in one month and had to return home, she had to pay back my flight, visa, food, and lodging costs. I understood and told my mother I would. I thought, if I failed, my mother would have to go to jail because we were so poor that we could not pay back our debt.

I was staying at the matchmaker’s home. I cleaned his house, did laundry and looked after his two children for free. His house was close to a clock shop. One day an old woman passed the clock shop. She was on her way to go to a Chinese medicine clinic for her knee pains. She stopped at the clock shop and the man asked whether her sons were married. She said neither of her two sons was married. The man suggested me to be her daughter-in-law. She looked at me and she decided she liked me. So this was how they married me to her younger son, although I knew nothing about their decision.

She rang her younger son who was working at a factory in a neighbouring town and asked him to return home to see me. The son refused to come home; he did not want to get married with a foreign woman. But she ordered him to come back and he did. He came to see me and he liked me, so the deal was made that I would marry him.

They took me to the village where their family was based without telling me what this was about. My hometown in the Philippines is very different from their village. I thought that was for my holiday and sightseeing. We had lunch in the main room of the house in front of the deity statute. The lunch turned out to be my engagement party and they picked a good day to marry us.

Three days later I got married with my husband. They brought someone to do make-up for me and they also brought me a bridal dress. Lots of people came to the wedding banquet. My husband quit his job and returned home, working on the family’s farm. Our neighbours were nice and some of them enjoyed gossiping: they came to see me and asking me what life was like in the Philippines. I am the first Filipina wife in the village. After me, there were other Filipino women coming to the village. One of them is still there.

I liked the village very much. I enjoyed staying there. But, in the beginning of my marriage, I cried every day when the sun set. I thought that was the end of my life. My mother-in-law said she knew that I was homesick and scared. To calm me down, she suggested she sleep together with me so that she could be in my company. It helped a little. My mother-in-law taught me everything. In six months, I began to be able to speak Taiwanese, which I learned from her. She also taught me how to cook Taiwanese food. Every day I cooked the breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I also grew vegetables. I did not know how to do it before coming to Taiwan. I also cooked Filipino food for them and told them what each dish was called in Tagalog. They ate my cooking but told me the dishes were too salty. My mother-in-law also taught me how to prepare for worshipping the deity and all other activities required by local folk belief. As a Christian, doing ‘bai bai’ (拜拜, worshipping and offering sacrifices to deities and ancestors) does not bother me. These are local customs that I respect; practicing it does not interfere with the relationship between me and God. My faith is in my mind, in my heart.

My eldest son was born one year after I got married. The first three years of my marriage were spent on the constant thought of committing suicide, until my second child, a girl, was born. I now knew that I had to look after my children; I had to be responsible for my home. This is my home.

I took part in school activities a lot so I knew my eldest son’s teacher very well. The teacher told me that I could go to those evening classes for illiterate citizens who cannot speak Mandarin. My mother-in-law allowed me to go – in fact, even if she did not allow me to go, I was determined to go. I was naturalised two years after moving to Taiwan. My mother-in-law did not obstruct my application for naturalisation. I relinquished my Filipino nationality and that was fine. I like Taiwan. I spent more time in Taiwan in my life than in the Philippines. My Filipino passport was cut and retuned to me. That was fine. I did not feel bad about it.

I had a dream that when my eldest son finished his university education, I would open a shop and run a remittance business. Twice I told my husband about it; twice he rejected. I was mad. I thought that I had supported him and his family by working for them for so many years. In return, they should support me. By coincidence, I overheard my mother-in-law’s conversation with my husband. She did not approve of my idea of running a shop; she said that if I chose to leave home for that plan, she would chop my feet off! She was mad at my plan; I was mad, too, to hear about this – I am not a robot working all day for them. So I left.

_

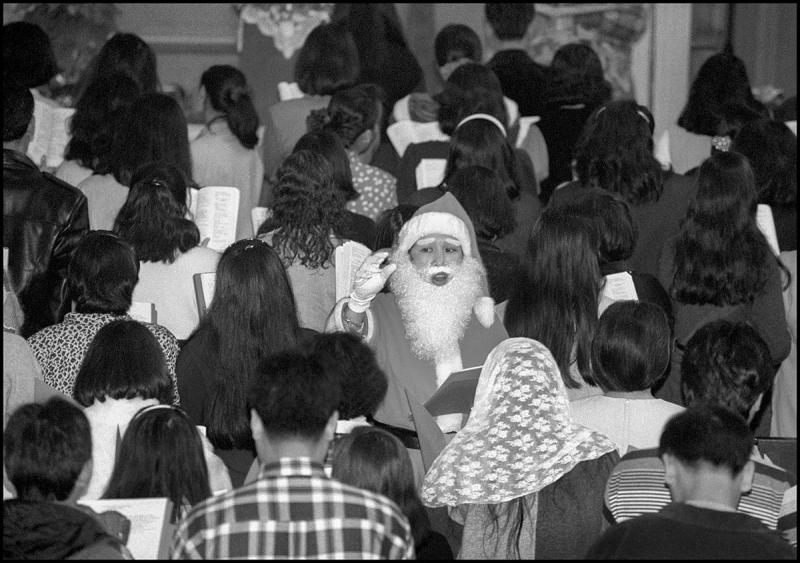

Fig. 2: Father Christmas at a Christmas Mass. (Photo courtesy of Tzu-ming Huang)

Some of the Filipino women who married Taiwanese men also became matchmakers. I had no interest in becoming a matchmaker. Being a foreign wife is so difficult that I didn’t think it was good for anyone to do it. Now, if someone asks me for advice on getting married with Taiwanese man, I would ask what her motivation is. I did feel I was discriminated in the village, but I could not explain what that was. I felt it; I heard it. Knowing that discrimination was around was partly why I had to leave. I wanted to make my life better.

I needed a job to support myself. In two years, I did three jobs every day. From 5:30-9:00 in the morning, I worked at a breakfast café. From 10:00-16:00, I worked at a steak house. From 17:00-23:00, I worked at another steak house. I could deal with them. Sometimes, when the situation is difficult, you’ve got to stay strong. I didn’t tell my mother about leaving my marriage. Up to now, she still doesn’t know about it. I was reluctant to tell her because she couldn’t do anything about it, because I didn’t want her to have a troubled mind and because I didn’t want her to be hurt.

I did these three jobs for two years until I returned home to visit my mother. Her boiler was broken, so I bought a new one for her and stayed there a month. After coming back to Taiwan, I found a job at a factory. I worked there for seven years. I was planning to continue to work there till my retirement.

After I left home, my husband and parents-in-law did not try to contact me. It was I who rang home every now and then and asked about my children. Later on, my husband divorced me. I maintained contact with my eldest son when he was studying at the university. I had his number and I went to see him. But later on his number did not work anymore. Perhaps he had lost his phone. I resumed my contact with my family recently. I went to visit them in the village. They knew why I left home so they did not ask me about it. My youngest son is not married. He told me he’s not going to marry anyone. I’m worried.

Seven years after my job at the factory, I was asked by the broker who sourced Filipino workers for my factory whether I wanted to work for them as their interpreter. I wasn’t sure whether I could do it, but they said I should give it a go, so I did. I like my job, which I’ve done well. Doing this job can improve my Tagalog! I hadn’t spoken it for a long time and it felt rusty. Some of the new vocabulary and slang felt alien to me, but I can pick it up from my workers.

For migrant workers in Taiwan, working at a factory is better than working at home as a carer. Factory workers have more freedom. After they finish their work, they are free. If they are asked to work overtime, they get overtime payment. Most of them would buy a second-hand scooter after coming to Taiwan. They could try to find information about it by reading Facebook posts. It costs roughly 15,000 Taiwan Dollars (approx. 340 Euros). I like to stay in Taiwan. Some of my workers wished to stay in Taiwan, too, after working in Taiwan for 12 years. They have to pay roughly 60,000 Taiwan Dollars to a recruitment agency to be hired by a Taiwanese employer, so their salary is deducted to pay for the recruitment fees. My factory would keep hiring the people who have finished their contract without going through a broker because they are skilled workers.

Since I became an interpreter, a lot has changed in my job. In the past, it was very easy to communicate with the workers. Whenever a new worker came, I explained to them about government regulations, factory rules, and dormitory rules. Now, they have become more independent-minded. They ask a lot about their rights, for example, whether they have annual leave. They do – after they finish the first year, they can get seven days as their annual leave. Some of them decide to go home, so I will apply for an exit permit to the National Immigration Agency for them. All of the workers whose annual leave were processed by me returned to Taiwan, no one went missing!

I lead a Bible study group in my dormitory for my workers and also at the Church. Every Saturday and Sunday we come to the church. We celebrate Christmas, Easter, and birthday together; we also organise dedications for the children of the wider Christian community, which includes non-Filipino people. The church is like a home and I’m everyone’s mother – they call me mummy. We work hard during the week; coming to the church can help us relax. We form a fellowship; we sing and read the Bible together. If workers do not have a place to go during the weekend, they may turn to drink and gamble. Women may get pregnant regardless of being a factory worker or a carer. It is their body and they have the right to decide what they want to do about it. By law, pregnant workers can stay. Some factories allow them to stay, and after going into labour and giving birth, they can return to work. Other factories will dismiss pregnant workers and send them back to the Philippines. This is because, to hire migrant workers, employers have to sponsor workers’ visas and pay the Employment Stability Levy to the government, so they wouldn’t like the fact that they pay for the Levy for nothing. Some of the babies went to the women’s families – their relatives came to Taiwan and brought the baby back home.

I worked hard and whatever I managed to save, I gave it all to my mother. I talked to her every month or every other month. My mother and grandmother used to be separated from each other. I couldn’t be happier to see them reconciling with each other after many efforts made by me. In the past four years, I went back home every year. I wanted to bring my mother and grandmother to stay with me in Taiwan. This is my dream. But my step-father had a stroke and required my mother’s care, so the dream is yet to come true.

To look back at my life, I feel blessed – how good and faithful God is because after all these years, I overcame all the difficulties with the strength and guidance and provision God has given to me. I hope sharing my story will give encouragement to others, especially those in difficult situations.

No matter what hardships life may bring, God is there for us.

Add new comment