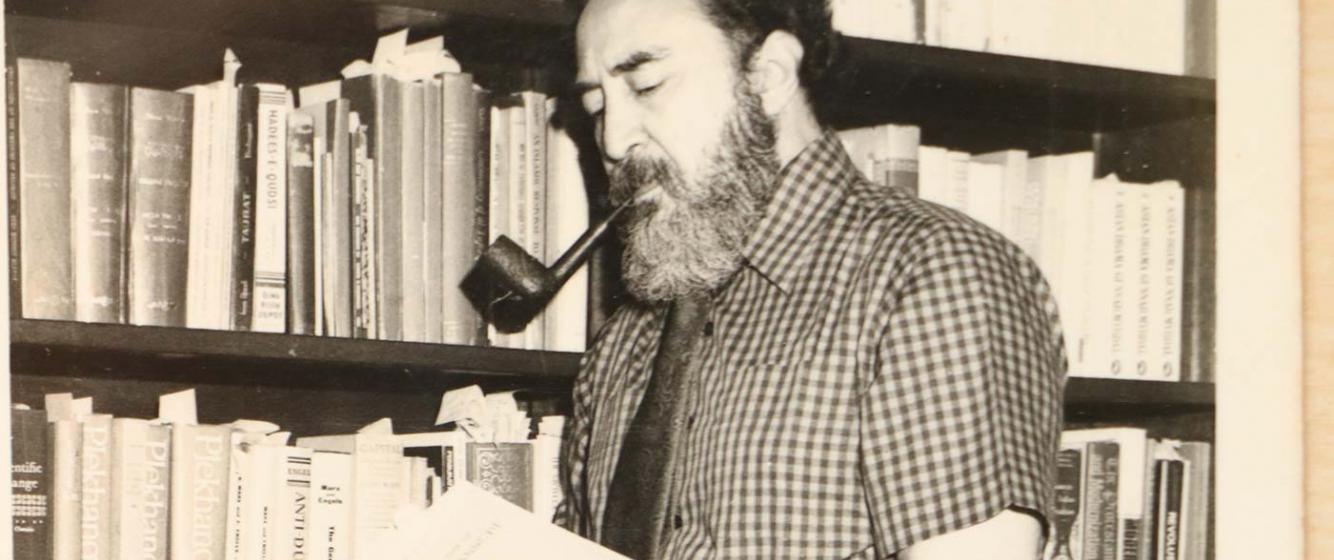

Syed Hussein Alatas (Photo courtesy of Syed Farid Alatas)

Revisiting the “Captive Mind:” Intellectual Imperialism in the Contemporary Asian Academy

Looking back at the formation of academic research and institutes in Asia, Syed Hussain Alatas wrote an influential paper describing the situation as “intellectual imperialism.”

He argued that even if actual colonial power structures were dismantled, there still remained, in large segments of contemporary Asian academic production, a “captive mind” which was “incapable of forming original problems” due to the continuation of structures which privilege modes of knowing directly imported from Western scholarship.[1] Syed Farid Alatas continued his father’s work, theorizing a “global division of labour” where the non-West continued to be dependent on Europe and North America for theoretical and material resources for academic production.[2]

This collection seeks to understand and critically examine the relevance of intellectual imperialism today as Asian universities pursue a goal of internationalisation in attempts to reach a global standard. Policies such as the promotion of publishing in journals with an “impact factor” (i.e., journals which are operated from the imperialist centres of Europe or North America), or hiring academics trained in these centres over indigenously trained academics, are examples of such efforts. These policies coincide with ongoing developmentalist logics in which discourses from the imperialist centres continue to shape academic disciplinary knowledge production in Asian countries.

The collection stems from a panel at ICAS12 in August 2021, which consisted of the four presenters and Syed Farid Alatas as the discussant. Takamichi Serizawa discusses the postwar Japanese academic dependency on the US, which ushered Southeast Asian studies while forgetting the Japanese wartime study on the region, especially the Philippines. Narumi Shitara uses the method of citation analysis to examine key characteristics of published research that have been incorporated into Japanese Southeast Asian Studies. She demonstrates increased citation of English-language or English-native counties’ articles – and decreased citation of Southeast Asian languages or journals published in Southeast Asia – by Japanese scholars since 2000s. Boon Kia Meng explores the possible and little-discussed connections between the “captive mind” phenomenon and Malaysia’s history and experience of counterinsurgency, a late British colonial effort that has since been extended and normalized in postcolonial Malaysia. Nishaant Choksi and Jaison Manjaly discuss the “captive mind” in Indian academe, pointing out the increasing privatization and internationalization of higher education in India. Even though India gained independence from the British around 70 years ago, intellectual imperialism still continues because the upper-caste class (savarna) controls the production and dissemination of knowledge and tends to mimick Western scholarship.

Although each presentation tackles independent topics, all share the same problem at the fundamental level: the more we try to study the issues surrounding Asia, the more we realize that the wall “first” built by Western academic imperialism continues within local scholarship and in the work of postcolonial elites.

Takamichi Serizawa (Kyoto University)

Nishaant Choksi (IIT-Gandhinagar)

[1] Alatas, S. H. (2000). Intellectual imperialism: Definition, traits, and problems. Asian Journal of Social Science, 28(1), 23-45.

[2] Alatas, S. F. (2006). Alternative discourses in Asian social science: Responses to Eurocentrism. Sage.

Comments

PhD Candidate in sociology

Je suis doctorant en sociologie à l'Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar. Comment soumettre un article à IIAS

IIAS contact

Please drop us a line at thenewsletter@iias.nl

Add new comment