The Future of Hong Kong: Conceptualizing, Researching, and Teaching About Hong Kong at a Time of Uncertainties

On the late night of 30 June 2020, the moment before the twenty-third anniversary of the sovereignty handover, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) bypassed Hong Kong’s legislature and imposed a national security law on Hong Kong, without addressing the concerns expressed by many journalists, scholars, and diplomats for its possibility of arbitrary interpretation, extra-territorial law enforcement, and potential threats to academic freedom, press freedom, and the freedom of expression.[1] Observers marked it as the end of “One Country, Two Systems,” as it violates a legally binding international treaty, the Sino-British Joint Declaration (1984), as well as the city’s post-handover mini-constitution, the Basic Law.[2]

Introduction

The draconian Hong Kong National Security Law (HKNSL hereafter) could be seen as China’s hard-line response to the city’s continuous struggles for democracy, liberty, and the promised “high degree of autonomy.” Such struggles included the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014 and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement (also known as Anti-ELAB Movement or Anti-Extradition Movement, 2019-2020), an unprecedented series of leaderless protests triggered by a controversial bill that would allow the extradition of suspects to China. The brutal police crackdown on the movement and abuse of the detained have turned Hong Kong from one of the world’s safest cities into a place marked by turmoil and authoritarian governance.[3] Many ordinary Hongkongers seek to emigrate, leading to the largest exodus of Hongkongers since the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989.[4] By June 2021, Hong Kong faced its most significant population decline since the documentation of such data in 1961.[5]

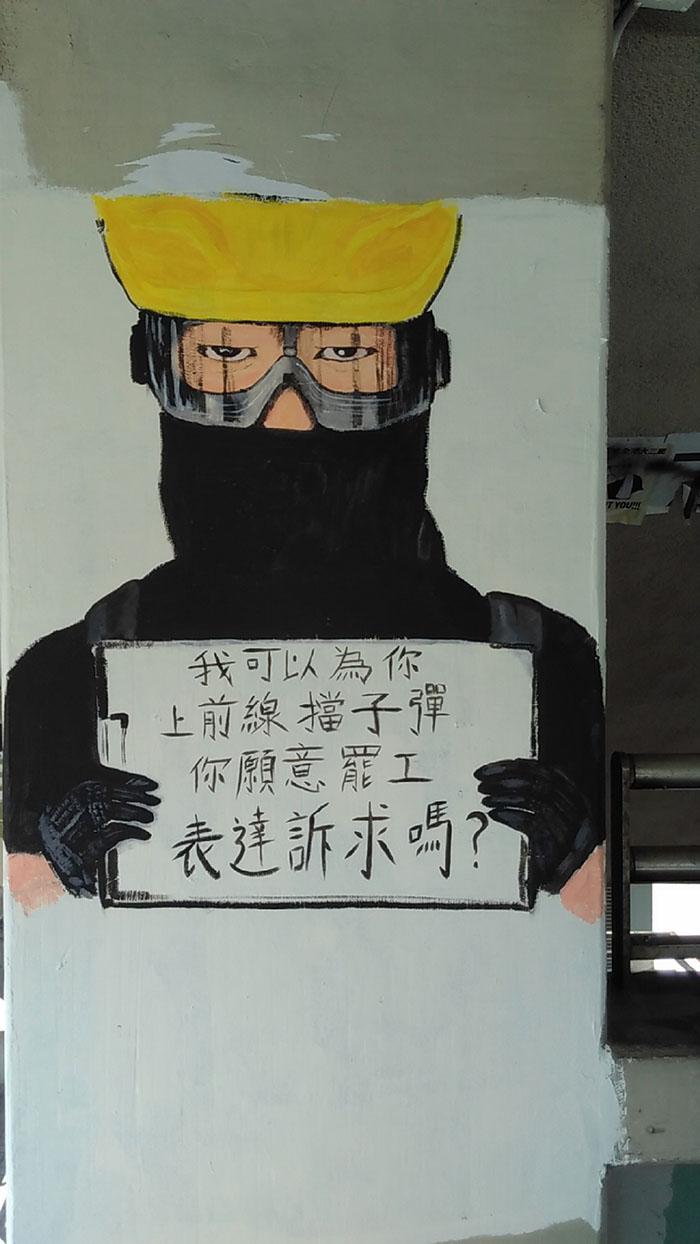

Fig.2: A piece of protest art during the Anti-ELAB Movement

Despite uncertainties about the fate of the city, we have observed growing global interests in Hong Kong Studies, evidenced by the increasing number of Hong Kong-related academic societies, programmes and courses, online seminars, and calls for publication. However, the HKNSL and the tightening socio-political control have put local and overseas scholars who teach and research Hong Kong in a precarious and ambivalent position that requires attention. Thus, we gathered a group of early-career Hong Kong Studies researchers from diverse humanities and social sciences backgrounds based in Asia, Europe, and North America to address the precarity of teaching and researching Hong Kong. We aimed to come up with a more flexible, organic, and innovative theoretical framework to understand Hong Kong and reflect on how researching and teaching about Hong Kong in a time of uncertainties can inform the broader humanities and social sciences scholarship.

The roundtable for ICAS12 was initially planned in September 2020. By the time we held the roundtable in August 2021, things had escalated at a pace beyond the expectations of many roundtable participants. This did not only evidence the urgency of such reflections and dialogues, but also lead us to rethink the potential impacts of the HKNSL on researching and teaching about Hong Kong. When our roundtable took place, the election system of Hong Kong was already re-engineered to reduce the Hong Kong public’s voting power.[6] Universities were distancing themselves from students’ unions,[7] which ultimately led to the disbanding of such unions by the time when we wrote this blog post.[8] News was also spreading about students reporting professors in Hong Kong for violating the HKNSL.[9] Among other civil society organizations, the largest and most prominent teachers’ union in Hong Kong was also set to disband, citing the changing political and social situations.[10]

On top of numerous existing arrests resulting from the leaderless anti-ELAB protests in 2019-2020, many pro-democracy activists, politicians, and journalists have been arrested, detained, and routinely denied bail under the HKNSL. Activities ranging from participating in election primaries to publishing children’s books have been cast as “sedition,” under a colonial-era law reactivated by the Hong Kong SAR government.[11] Even activists based overseas or in exile have been wanted for “violating the national security law.”[12] The pro-democracy Chinese-language newspaper Apple Daily was forced to shut down after two raids (August 2020 and June 2021), the freezing of its assets under the HKNSL, and the arrest of its owner and executives.[13]

Fig. 3: A candlelight vigil held in Victoria Park, Hong Kong to commemorate the Tiananmen Massacre. The candlelight vigil took place every year until it was banned by the Hong Kong government in 2020 (in the name of Covid pandemic prevention). Despite so, many Hong Kong people defied the ban. The organizer of the vigil, Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, was dissolved in 2021. (Photo image via inmediahk, Creative Commons: Attributive, Non-Commercial)

The roundtable for ICAS12 was to provide a platform for early-career researchers from different humanities and social science disciplines based in Asia, Europe, and North America to share our concerns and future visions towards Hong Kong Studies. Participants include Drs. Mung-Ting Chung (University of Calgary, Canada), Eva C.Y. Li (Lancaster University, UK), Florence Mok (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore), Nick H.K. Or (City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong), and Desmond H.M. Sham (National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taiwan). We exchanged our thoughts on the precarity of researching and teaching Hong Kong, our concerns about the disappearance of data related to Hong Kong studies, and our visions towards the future of researching and teaching Hong Kong.

Desmond H.M. Sham (International Center for Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taiwan) & Eva C.Y. Li (Department of Sociology, Lancaster University, UK)

[1] See, for instances, Hong Kong Bar Association (2020) Statement of Hong Kong Bar Association on Proposal of National People’s Congress to enact National Security Law in Hong Kong, 20 May. Available here (Accessed on 30 December 2021); Amnesty International (2020) Hong Kong’s national security law: 10 things you need to know, 17 July. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/07/hong-kong-national-security-law-10-things-you-need-to-know/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021); Normile, D. (2020) Hong Kong universities rattled by new security law, Science, 1 July. Available at: https://www.science.org/content/article/hong-kong-universities-rattled-new-security-law (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[2] Yu, V. (2020) The “real” handover: Hong Kong fears looming laws will end “one country, two systems”, The Guardian, 27 June. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/27/hong-kong-fears-freedoms-will-end-as-new-law-looms (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[3] Amnesty International (2019) Hong Kong: Arbitrary arrests, brutal beatings and torture in police detention revealed, 19 September. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/09/hong-kong-arbitrary-arrests-brutal-beatings-and-torture-in-police-detention-revealed/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[4] Cheng, L. and Tsang, D. (2021) National security law: welcome mats by Britain, Australia, Canada lure thousands who feel Hong Kong is no longer home, South China Morning Post, 30 June 2021. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3139232/national-security-law-welcome-mats-britain-australia-canada (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[5] The Government of the HKSAR (2021) Mid-year population for 2021. Available at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202108/12/P2021081200387.htm (Accessed on 20 January 2022).

[6] Reuters (2021) Hong Kong passes sweeping pro-China election rules, reduces public's voting power, 27 May . Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/patriots-rule-hong-kong-sweeping-pro-beijing-electoral-rules-passed-2021-05-27/ (30 December 2021).

[7] Wang, V. (2021) “It feels like we’re just waiting to die”: Hong Kong targets student unions, New York Times, 31 July. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/31/world/asia/hong-kong-students.html (Accessed 30 December 2021); Magramo, K. (2021) Fifth Hong Kong university student union facing uncertain future, as school says it will no longer collect membership fees, South China Morning Post, 15 July. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3141198/fifth-hong-kong-university-begins-distance-itself-its (Accessed 30 December 2021).

[8] Ho, K. (2021) “Chinese University Student Union ‘forced to dissolve in such an ugly way,” ex-leader says, Hong Kong Free Press, 8 October. Available at: https://hongkongfp.com/2021/10/08/chinese-university-student-union-forced-to-dissolve-in-such-an-ugly-way-ex-leader-says/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[9] McLaughlin, T. (2021) How Academic Freedom Ends, The Atlantic, 6 June. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2021/06/china-hong-kong-freedom/619088/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[10] Chau, C. (2021) Hong Kong’s largest teachers’ union to disband following pressure from gov’t and Chinese state media, Hong Kong Free Press, 10 August. Available at: https://hongkongfp.com/2021/08/10/breaking-hong-kongs-largest-teachers-union-to-disband-following-pressure-from-govt-and-chinese-state-media/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021); CIVICUS (2021) Civil society groups forced to disband as activists and critics prosecuted in Hong Kong, 19 November. Available at: https://monitor.civicus.org/updates/2021/11/19/civil-society-groups-forced-disband-activists-and-critics-prosecuted-hong-kong/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[11] McLaughlin, T., Mahtani, S., and Yu, T. (2021) Every prominent Hong Kong activist now either in jail or exile, The Independent, 28 February. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/hong-kong-activists-jail-exile-beijing-b1808814.html (Accessed on 30 December 2021); Cheng, S. (2021) Hong Kong top court rejects bid to appeal bail refusal for speech therapist over “seditious” children’s books, Hong Kong Free Press, 11 December. Available at: https://hongkongfp.com/2021/12/11/hong-kongs-top-court-rejects-bail-for-group-charged-with-sedition-over-childrens-picture-books/ (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[12] BBC News (2020) Hong Kong “seeking arrest” of fleeing activists, 31 July. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-53616583 (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

[13] Cheng, L., Lo, C., and Wong, N. (2021) Hong Kong’s Apple Daily to stop publishing online at midnight, printing 1 million copies for its final edition on Thursday, South China Morning Post, 23 June. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3138399/national-security-law-apple-dailys-main-editorial (Accessed on 30 December 2021).

Add new comment