Troubling the Chinese Tiger Mom

When interviewing parents in Beijing and Shanghai about strategies surrounding their children’s education, one reoccurring topic was the parenting style of the “tiger mom” (虎妈, huma). Depicted as a mother who does everything for her child, but also demands everything from the child, the tiger mom takes on the status of a “fetishized other,” upholding unattainable standards of discipline, endurance, time management skills, and competencies to set out the most conducive trajectory for optimizing the cognitive and academic development of her child. She is familiar to everyone, and basically everybody can pinpoint a personal example. Through snowball sampling, several of my interlocuters introduced me to their tiger mom friends. Yet, no one I spoke to identified with this characterization. The reason the tiger mom is at the same time omnipresent and non-existent, I argue, is that middle-class parenting in urban China today is much more complex and infused with anxieties and dilemmas, juggling academic performance and mental well-being, than what the tiger mom persona epitomizes.

Still, the tiger mom matters. She exists as an imagined supermom who personifies the ultimate and purest form of the parenting style known as concerted cultivation.[1] As opposed to natural growth, which signifies a parenting style where the child is left with much more freedom to explore the world on their own terms, concerted cultivation implies intense educational labor on the part of parents through the mobilization of private tutors, extracurricular school activities, and various leisure activities, such as sports and music classes.

Though none of the mothers in my study self-identified as a tiger mom, some fathers would refer to their wives as tiger moms. This was the case in the family of Wang Wei, a father in an upper-middle class family with a child in grade four in one of the highest-ranked primary schools in China. Upon the birth of their child, Wang Wei’s wife had become a “fully-employed mother” (全职妈妈), quanzhi mama, a term which suggests that she is not primarily a housewife, attending to the care and maintenance of the home. In fact, the family had a housekeeper who did the cleaning, laundering, and cooking six days a week. Wang Wei’s wife was putting her time, energy, skills, and experience to use to engage in educational labor, working towards their child becoming an “elite kid” (牛娃, niuwa). Wang Wei’s wife managed the child’s schedule as tiger moms typically are expected to do: extracurricular activities were planned for every day of the week, weekends included, except Wednesdays. Yet, with extra classes in math, English, and Chinese, intensive participation in sports, and piano, which required an hour’s practice four times a week, even Wednesdays were filled with homework and practice, and Wang Wei related that there was no time for the child to play at all. The mother took the child to sport classes at the other end of the city twice a week, so the child did not go to bed until 11:30 PM on those nights, despite the next day being a regular school day. On those days, homework had to be done in the car and in a specially designated homework venue at the sports facility while waiting for training to start, and in between one-on-one training and group training sessions. This education plan for their child was decided by – and was the responsibility of – the mother. Wang Wei referred to himself as a “lamb dad” (羊爸, yangba), one who is soft and never gets angry. In fact, the lamb dad and the tiger mom form a dyad, where the lamb dad in some ways is a prerequisite for the tiger mom, helping to ease some of the pressure placed on the child and thereby making sure the education plan is actually maintained. He stays calm when she gets angry. While she plans a long and busy schedule of extra classes and homework that allows no play, he eases that schedule in a small but significant way by having a secret agreement with the child: for every hour of homework and practice, the child can spend five minutes on free play.

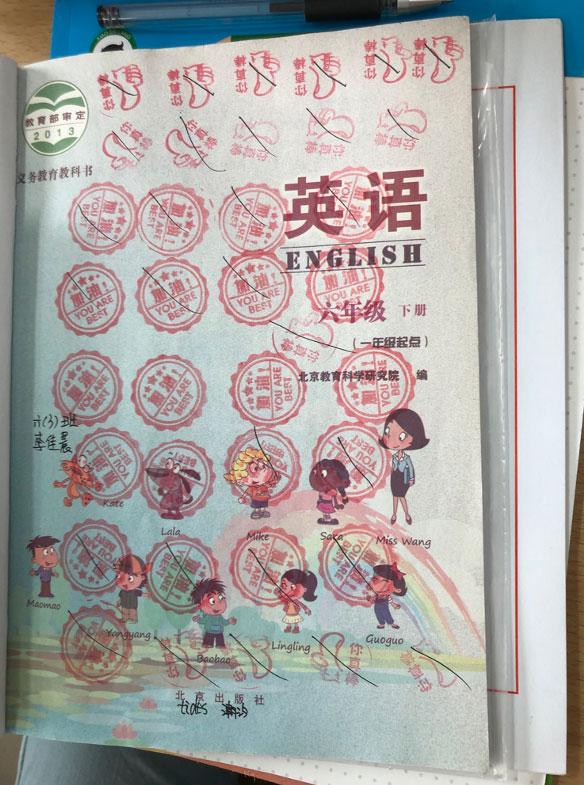

In order to reward hard work and spur motivation, students get stamps when they perform well on tests. A certain number of stamps amount to a small gift. (Photograph courtesy of the author, 2019)

Similar to other parents interviewed, Wang Wei was concerned that the child is under too much pressure, yet he sees no room for reconsidering the way they have set up the child’s education and adjacent activities. His reasoning was that the hardship the child goes through now will pay off in the future and that being part of the elite requires hard work. In this sense, Wang Wei spoke with admiration and pride about his wife’s tiger mom parenting style. With the hope of finally being able to talk to a real tiger mom, I asked if I could interview Wang Wei’s wife. Regretfully, she had no time; she did not want to be troubled.

Or was she too a fetishized other who found the tiger mom ideal troubling?

Lisa Eklund is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Lund University. Her research is situated in the nexus between family sociology, social policy, and population dynamics. She has written extensively about son preference, sex-selective abortion, mate selection, intimate relations, gender and intergenerational relations, and parenting strategies in China and beyond.

[1] Anette Lareau, Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life (Berkely: University of Califorina Press, 2003).

Comments

Hi Lisa, my research in…

Hi Lisa, my research in Jakarta also found the same thing, and my respondents were mostly the moms. It is very interesting indeed. Would be great to exchange our studies on this interestkng topic 😊

sociology

Hello Lisa,

I find your research so interesting! I was fortunate to be admitted to a great high school in my hometown, Shenyang NO. 20 high school, where I met many niuwa classmates. The interesting thing is that their "tiger moms" are still trying to control them, even though they are adults now. Your short blog inspires me to learn more about this topic, and the underlying logic about huma and yangba.

Thank you!

Add new comment