“Play with Passion! It Will Lead You to Perseverance in Study”: Negotiating Parents’ Aspirations through Play in Seoul

Similar to both Singapore and China, parents’ educational work in Korea appears complicated, and their aspirations emotionally ambivalent. During our field work in Seoul, we noticed Korean parents’ increasing awareness of their children’s emotional well-being during early childhood and its fundamental effects on their children’s later development. This trend is well-illustrated when parents talk about how they facilitate and coordinate their children’s play, leisure activities, and cultural experiences. The growing interest in the impact of play and the importance of a less stressful childhood has become apparent not only in the Korean government’s reform ideas for public education, but also in the private educational market. Parents’ motivations can be paradoxical when it comes to play: they hope that it will both enhance their children’s academic performance in the future, while at the same time allow them to enjoy their childhood.

During fieldwork, we met three mothers from a local community organization, “Play Together.” This organization hosts regular meet-ups and play dates featuring a variety of fun activities that allow both children and adults to participate. Ironically, the organization is based in a hot spot of high educational fever in Seoul. The mothers experienced their children struggling with a competitive environment and stiff, all-consuming education. They came to the conclusion that it is more important to have a place and time for children to play together with their parents. The children have the freedom to choose the type of play activities they participate in whenever they come together. When we went to observe one of the events, we could see parents paired up with their own children and actively taking part in the activities. Involvement in this organization does not mean that their children are free from private education. Nevertheless, the parents wish to continue their involvement for the sake of managing their children’s social interactions. One of the mothers emphasized the potential advantage of play to her children, telling them to “play with passion! Then the passion will lead you to perseverance in studying.”

Children’s right to play has been highlighted in policy since the 2010s. In 2019, the Ministry of Education (MOE) reformed the national curriculum for children aged 3-5, focusing on play-oriented curricula.[1] Yuri and Minho, decided to send their two children to an “Innovation School,” which was introduced as part of the reform. This elementary school spotlights self-directed learning and play. Their mother was trying hard not to be swayed by other parents who prioritized preparation for accelerated coursework spanning several months to three years, with the intention of excelling in later stages of their education. Yet, at the same time, she admitted that she was anxious about her child not following the same path as other children.

The trend of focusing on the advantages of play-based learning has been adopted by the private education market. Suhee, a mother of three children, is a customer of a “play-sitter” service. She hired a play-sitter for her two-year-old child, and the sitter visited her home once a week. To set up this service, she shared information about her child’s age, characteristics, and disposition with the manager of the company. The manager shared this information with registered sitter-cum-teachers and received their applications. Suhee looked through the applicants’ CVs and their self-introduction letters, ultimately choosing a college student majoring in dance education.

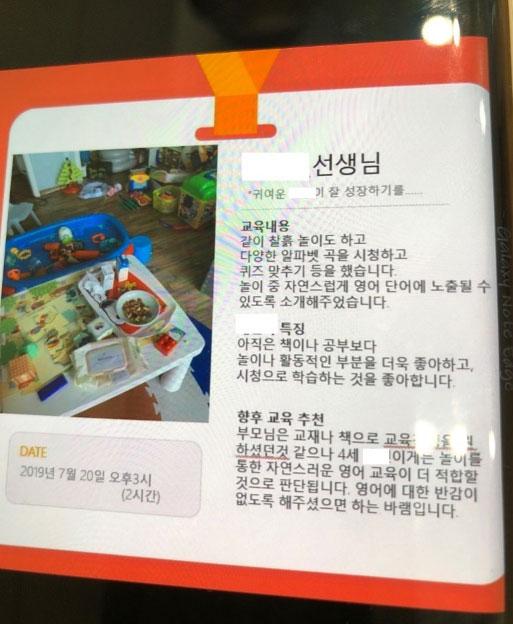

Figure 2: A play sitter’s report on Bomin’s activities (4-yr old boy): “We played with clay and listened to alphabet songs. Making Bomin naturally exposed to English words […] For his age, natural ways of learning English through play are more appropriate. I hope that he would not have any dislike against English.” (Photograph courtesy of the authors, 2019)

When we met a managing director of another company in the play-sitter business, we heard similar stories. For instance, he introduced a college student majoring in acting and aspiring to become a news anchor to the parent of a seven-year-old child. The parent wanted their child to learn to speak Korean accurately, so they expected the play sitter to have clear pronunciation. The parents seem to be willing to pay 20,000 KRW (about 14 EUR) per hour to hire a professional play sitter. On the other hand, while some parents try to stop their children from playing video and computer games, there was a parent who wanted someone who could teach her child how to play Minecraft, a famous computer game among young children, so that the child could get along with their peers. Play-sitters seem to be desired for children’s physical, cognitive, and language development, as well as their psychological well-being.

An increasing emphasis on children’s play reveals how Korean parents try to compete and negotiate their seemingly paradoxical desires for their children.[2] The parents want their children to be academically successful, yet at the same time, they want their children to be happy. Korean parents thus consider play to be a crucial activity that promotes children’s psychological well-being as well as enhances their physical and cognitive development. Additionally, play-based learning is believed to instill children with positive attitudes towards education by encouraging them to find learning fun and enjoyable. In this way, Korean parents are able to reconcile their ambiguous aspirations for their children, which are closely associated with their shifting notions of childhood, education, and parenting in contemporary Korea.

Yoonhee Kang is a Professor in the Department of Anthropology, at Seoul National University. Her research focuses on a variety of issues, including parenting and education, as well as migration and language in Korea, Singapore, and Indonesia.

Yeon-Jin Kim is a PhD candidate of Social Work at Lund University. Her work focuses specifically on Korean fatherhood in policy and practice. Her current research is situated at the intersection of culture, fatherhood, and social policy. She has written on topics such as parental leave policies in Korea and Sweden, policy transfer, Confucianism, work norms, sense of entitlement, fathers’ community, and parenting strategies in Korea and beyond.

[1] “Press release: July 19 2019”, Ministry of Education Korea, accessed April 1, 2023, https://moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=294&boardSeq=78061&lev=0&searchType=null&statusYN=W&page=1&s=moe&m=020402&opType=N.

[2] Kristina Göransson, Yoonhee Kang and Yeon-Jin Kim, (2022) “Navigating Conflicting Desires: Parenting Practices and the Meaning of Educational Work in Urban East Asia,” Ethnography and Education 17, no. 2 (2022): 160-178.

Add new comment