Ambivalences, Anxieties and Parents’ Educational Labor in Singapore

Singapore’s education system is famous for producing students who excel in international student assessment tests like the OECD’s PISA test. It is not strange, then, that the transition from pre to primary school is a major, sometimes daunting, step for parents and children alike.

During my fieldwork in Singapore, I met Jeff and Shuping, parents of two young children. At the time of my most recent visit, their oldest child was reaching the end of preschool. Jeff and Shuping were concerned about the transition to primary school, since their child struggled with learning to read. Their concern was not primarily whether or not their child would be able to pull through (he likely would, they said), but rather at what cost. What would be the toll on the child’s self-esteem? After giving it a lot of thought, Jeff and Shuping decided to relocate to another country, where they hoped they would find a less stressful environment and a school better able to meet their children’s needs.

Figure 1: A common sight in Singapore: Parents sending their children to afterschool enrichment classes and tuition sessions. (Photograph courtesy of the author, 2022)

In Jeff and Shuping’s case, education was a trigger to leave, but not in the conventional sense of optimizing academic achievement and opportunities. Rather, the motivation to leave was to protect the child from the potentially negative effects of an extremely competitive education system. The case of Jeff and Shuping reflects a growing tension between parents’ desire to achieve academic success and the desire to nurture the child’s emotional and psychological well-being. This tension was tangible, not just in Singapore, but in China and Korea too. What has been particularly striking is that parents’ sentiments of uncertainty and risk management are complicated, and indeed, heightened by paradoxical expectations with regards to children’s education and future, especially among the middle-class.

The growing concern for children’s emotional and psychological well-being is not driven by parents alone. On the contrary, there has been a shift in education policy towards so-called 21st century competencies: a framework emphasizing “new” skills believed to be essential to thrive in the new century, such as self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, and relationship management. While there have been reforms aimed at reducing the emphasis on grades and exams, academic achievements are still considered crucial to foster competitive individuals. During fieldwork, it was striking how parents of young children were torn between conflicting expectations: while they are still under pressure to play an active role in their children’s education (e.g. preparing for exams or overseeing homework), they are also expected to ensure them a happy and stress-free childhood.[1]

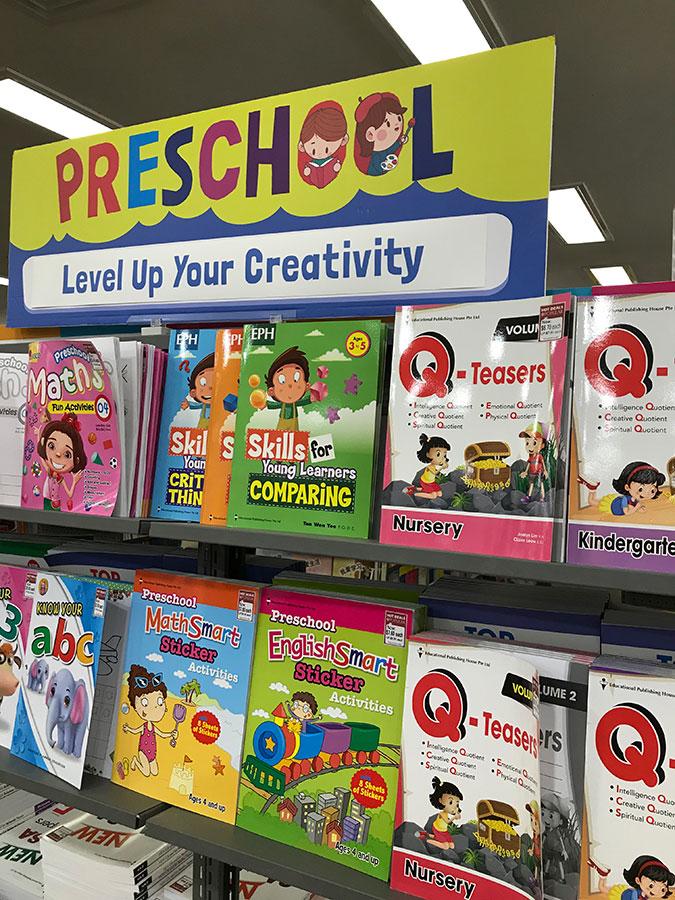

Figure 2: There is a wide range of supplementary assessment books and educational materials – even for preschool children – in local bookstores. These are very popular among parents, who use them for additional practice and assessment. (Photograph courtesy of the author, 2022)

This tension is also reflected in parent-led initiatives, such as Life Beyond Grades. Life Beyond Grades was started by a group of parents with the “aim to drive a mindset shift among all in Singapore, to alleviate the increasing pressures of school on our children”.[2] At the same time, the need to go beyond grades is framed as a means to an end, namely, to equip children to thrive in an uncertain future by “embracing the multiple pathways that each child can take in their journey towards success and happiness.”[3]

It is clear that Singaporean parents are highly ambivalent about the burden placed upon young children, but the fear of falling behind compels them to devote substantial energy, time, emotions, and resources to their children’s preparation for school and life.

Kristina Göransson is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Work at Lund University, Sweden, and holds a PhD in Social Anthropology. Her research primarily concerns family, intergenerational relations, parenting, care, and educational labour, with a specific focus on Singapore.

[1] Kristina Göransson, “Play with a purpose: Intensive parenting, educational desires and shifting notions of childhood and learning in twenty-first century Singapore,” Childhood 30 no.1 (2023): 24-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682221138460

[2] “Education: Life Beyond Grades,” Family.sg, accessed March 16, 2023, https://www.family.sg/life-beyond-grades.html.

[3] “Education: Life Beyond Grades.”

Add new comment