Segregation and Interaction in Asia's British Cities: Cosmopolitan Communities in a Colonial World

As bustling centres of multicultural interactions, Asia’s colonial cities served as cosmopolitan sites of cultural, political, and economic exchanges for both foreign and local communities. The establishment of colonial outposts in different corners of Asia resulted in a rapid urban transformation: populations mushroomed and diversified while old indigenous systems of administration were supplanted or appropriated as part of new imperial institutions of rule.

If we look closely at the colonial city, we can discern contestation and collaboration being negotiated in markets, workplaces, and social spaces. Communities learned to not only live and survive in complex and multicultural environments, but also to thrive by harnessing what colonial port-cities had to offer. From a global perspective, colonial cities were nodal points in the regional and global circulation of commodities, peoples, news, and ideas. Entwining local pursuits with global opportunities, communities constantly negotiated their status, identities, and cultures through the colony’s imperial, trans-imperial, and transnational networks. This paved the way for the formation of polyglot societies and unprecedented forms of engagement, enticement, and exclusion built along ethnic, class, and cultural lines.

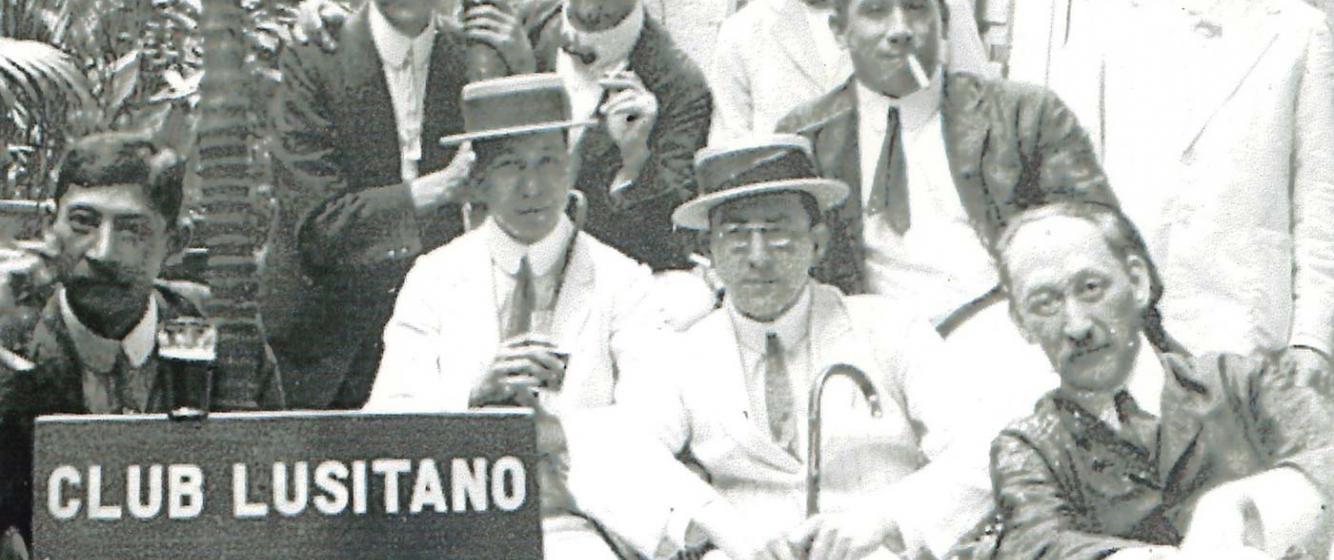

The studies featured in this collection explore the ways in which various communities manoeuvred urban worlds through global and urban lenses. Encompassing the British colonial cities of North Borneo (Sandakan and Jesselton), Penang (George Town), and Hong Kong (Victoria), our aim is to offer a more human-centred narrative that speaks to how marginal subjects of non-indigenous and non-European origins reworked rules of inclusion and exclusion against the ever-changing urban landscapes of these British colonies. How were such rules constructed through a colonial urban space? How did migrant communities build, maintain, or appropriate personal and professional networks? Focusing on North Borneo, Michael Yeo’s work examines the functions of ethnic-based organisations, sports clubs, and social spaces in drawing and reinforcing divisions between Europeans, Eurasians, and ‘Asiatics.’ As Yeo highlights, the inhabitants of Sandakan and Jesselton mingled, yet they might not have understood each other. The second section shifts to the northwest coast of Malaya in Penang, which Bernard Z. Keo reveals was coloured by the settlement and activities of ethnic and sub-ethnic traders and labourers from Asia and Europe. An innovative site for the discussion of local, regional, and global issues, Penang was home to newspapers in the English, Malay, Chinese, and Indian languages. The Peranakan Chinese, as Keo identifies, bridged Penang with the British, Dutch, and Japanese empires while maintaining historical links to the Malay World and China. Moving from Southeast Asia to East Asia, the last two works explore the urban terrain of British Hong Kong from the lenses of two communities that lived in the fringes of the colony – Macanese migrants and Chinese tailors. Through Club Lusitano and Liga Portuguesa de Hongkong, I trace the diversification of an ethnic group that existing literature has flattened into the category of Hong Kong’s ‘Portuguese.’ Established in two very different eras, these two organisations represented the segregation of the Macanese: the former secured the privileges of middle-class and Anglicised Macanese men while the latter pledged to invoke Portuguese patriotism amongst the colony’s young Macanese. Contributed by Katon Lee, the final post expands the theme of identity and class construction in British Hong Kong with a focus on Chinese elites. From the approach of material culture, Lee shows how middle-class Chinese men deployed western suits in displaying status and authority. More than adopting a new form of fashion, suit culture served as a form of social distinction that generated a sense of superiority amongst middle-class Chinese in early colonial Hong Kong.

From the activities of marginal communities, the four works featured in this collection will walk us through social and cultural spaces in colonial cities whose characteristics as simultaneous products and platforms of imperial, trans-imperial, and transnational interactions have so far been overlooked. Although having different scopes, the negotiation of solidarity and segregation are apparent. One thing that we can all reflect on, with regards to the past and the present, is whether solidarity can be achieved without creating differences and segregation. If the answer is no, how then do we move towards a world with less borders and more understanding?

Add new comment