The 2010 closure of the Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan border at Kara-Suu stemmed trade flows.

Bazaars without people: Chokepoints, redundancy and bypassing in Asian borderlands

When used together “bazaar” and “Asia” conjure images of teeming marketplaces. In part, this is a result of a tenacious orientalist trope for othering Asia; in part, it stems from one facet of globalization in which economic liberalization at the Cold War precipitated independent trading.

I define bazaars as places of independent, non-franchised trading. Over the course of my decade-long research on bazaars in Asia, I have visited three marketplaces—in Kyrgyzstan, the People’s Republic of China, and Pakistan—largely devoid of people. Bazaars, in which buyers are absent and sellers are few, is contrary to how we think of bazaars.

That these three markets are situated in borderlands—ostensibly places which would benefit from cross-border connectivity—is a reminder that proximity has not always resulted in increased trade flows, even when neighboring countries enjoy friendly relations.

Kara-Suu Bazaar, Kyrgyzstan: Chokepoint

“I could sell thirty of these at one time,” reminisced a local seller in Kara-Suu bazaar, his arm resting on a Samsung flat screen television. “I could sell fifty,” cried out his neighbour, not to be outdone. There was hardly place to walk in this bazaar, they said.

The sellers I was speaking with in southern Kyrgyzstan’s Kara-Suu bazaar were describing how trade had declined. Kara-Suu bazaar, where 15,000 people were estimated to work in 2013, is located in the town of Kara-Suu, along Kyrgyzstan’s border with Uzbekistan. After the Soviet Union, the bazaar had become a hub for light manufactured goods—many of which were imported from China—and the onwards distribution of those goods to neighboring Andijan province in Uzbekistan. At the turn of the century, the majority of buyers were from Uzbekistan; hence, Kara-Suu bazaar served a reexport function.

By my first visit in 2013, cross-border trade was a distant memory. In spring 2010, the border was sealed. One story I heard from traders was that Uzbek authorities wanted to stem imports from Kyrgyzstan in order to build bazaars in their own country. I am unsure if this is true, besides noting that bazaars in Central Asia provide employment and generate rent, benefiting a wide demographic. The border had become a chokepoint, after which trade in Kara-Suu bazaar declined. The recent discovery of secret tunnels—for smuggling between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan—is an illustration of discreet networks that bypass border chokepoints.

Kashgar, PRC: Redundancy

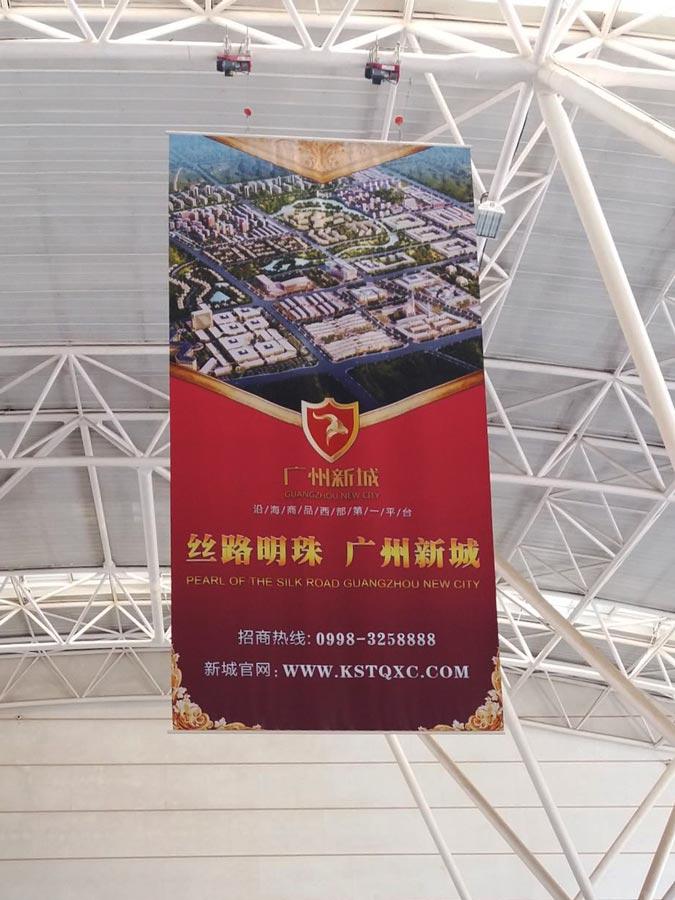

“Pearl of the Silk Road Guangzhou New City” proclaimed a banner at Kashgar airport when I landed in May 2017. But two days later, when I took a taxi to Guangzhou New City, my first reaction was to wonder whether I hadn’t been dropped off in the wrong place? Instead of a bustling commercial centre, I saw sprawling empty parking lots and massive, desolate malls.

At the inauguration of the Guangzhou New City in 2013, Xinjiang and Guangzhou party officials, as well as guests from Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan had been in attendance; the sprawling commercial complex was expected to increase the volume of goods from coastal Guangzhou into Xinjiang, and facilitate their onward distribution to Central and South Asian markets.

Although not a bazaar in the traditional sense, the Guangzhou New City was meant to be a hub for independent regional trade. The idea that Xinjiang would serve as a distribution hub went back to the 1990s. Economic liberalization, new markets and growing consumer power in the former Soviet Union and beyond had presented a tantalizing possibility: an Asia connected by dense commercial networks.

_

A banner advertising Guangzhou New City at Kashgar airport in 2017.

_

Guangzhou New City, 2017.

Exploring the empty Guangzhou New City, an obvious question came to mind: By itself, does building trade infrastructure spur trade? The small traders I spoke to in Kashgar in 2017 demurred when I asked them about the Guangzhou New City. “It’s too far from the city,” many of them told me. “Our networks are here in Kashgar,” others said.

The Guangzhou New City—as well as the neighboring Shenzhen New City—were also meant to attract investment and traders from namesake Guangzhou and Shenzhen in the east. This had not happened by my visit in 2017. “It’s too far away from coastal China,” a local resident explained to me. “There’s also a perception amongst the Han that Xinjiang isn’t safe for them. That has deterred Han businesspeople from outside Xinjiang from setting up businesses here,” he added.

Afiyatabad, Pakistan: Bypassing

The shop traders in Pakistan’s Afiyatabad bazaar had good reason to feel optimistic the future of the small marketplace. Situated a mere 75-kilometers from Pakistan’s only land border crossing with China, Afiyatabad and the surrounding villages on the Karakoram Highway, are the first so-called stop to and from China. Upgrade of the Karakoram Highway, that began in 2008, and the announcement in 2013 of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—one of the six economic corridors under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—led traders to believe that they would see increased activity in the marketplace. Pakistan and China are said to enjoy ironclad friendship. CPEC is described as a flagship of BRI. It was not far-fetched to assume that local sellers would benefit.

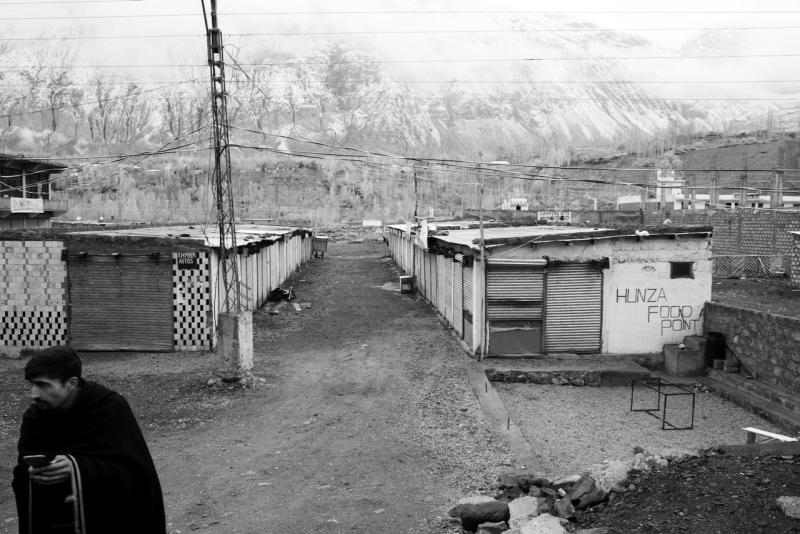

Many of the shops in Afiyatabad bazaar in northern Pakistan remain unoccupied; outside the summer tourist season, the bazaar is largely void of people.

But this has not been the case. Traders tell me that they benefited little from elevated ties between Pakistan and China. While cross-border traffic increased after BRI, the large consignment of goods and heavy machinery heads to markets or construction sites further away.

“The big cargo just rolls post us,” a long-term acquaintance of mine at the bazaar noted poignantly. Local communities, who using independent networks had previously supplemented household economies through cross-border trade describe themselves as being sidelined in a time of increased connectivity. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, new tariffs had made it less profitable for independent traders to cross the border. Here, upgraded connectivity infrastructure offered little benefit to the small trader, and instead channeled heavy cargo to distant locales.

By way of conclusion, the marketplaces I describe are noteworthy because they are located in borderlands, trading places one assumes would benefit from proximity to other countries. In the new century, a connected Asia has been repeatedly foretold, from former General Pervaiz Musharraf of Pakistan to Chinese President Xi Jinping. While there are limits to what one can extrapolate in a blog, the poignant reminder here is that an epoch of heightened connectivity, connectivity can either be ephemeral, and not everyone will benefit equally.

Hasan H. Karrar

Associate Professor,

Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani School of Humanities and Social Sciences

Add new comment